We have today a post from one of our marvellous team of Reserves, Maria McCann.

With Jane Borodale, Jane Feaver, Gabrielle Kimm and Michael Arnold,

I recently took part in a Historical Fiction Day at the splendid Weald & Downland Open

Museum in Sussex. The topic for our panel was landscape. I found myself focusing on it as I'd never

done before: what could I say about my use of landscape in fiction? What did I find most important and compelling

when writing about it?

I began by considering the psychological relationship between characters and their physical

environment. This has always interested me: how would characters have

understood the country surrounding them?

Would they conceive of it mainly in terms of inheritance, of money, of physical

labour and the many skilled tasks that make up farming, in terms of an enduring

(benign or oppressive) social order? Would

rusticity seem a refuge, or a banishment from everything that gave variety and

savour to life? Which modern

associations and resonances would be alien to them?

Religion would certainly shape their perceptions to some

degree. At this point I recognised something

more, something central to my own work that had previously been almost

invisible to me. (My unconscious, like

the shoemaking Elves, had done most of the work when my analytical mind was off

duty; I won't say that I was entirely unaware of it, but I'd never looked at it

head-on before.) I realised that lost Edens and false paradises

have always been central to my work, as have journeys, expulsions and the whole

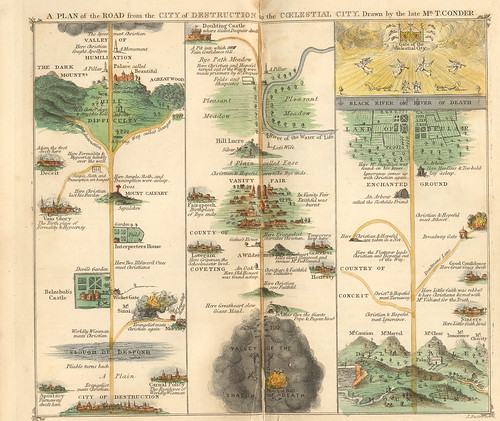

concept of life as pilgrimage that finds its most developed expression in The Pilgrim's Progress but stretches right

back to the Biblical metaphor of the narrow path to salvation versus the broad

road that leads to Hell.

Engraving by Thomas Conder. Photo: Jo Guldi. Licence: see flickr.com/photos/landschaft/7035370

As we all know, journeys in the past were slow and inconvenient, events in their own right. Novelists are often advised to cut

journeys from their narrative and jump straight to the arrival, but I love

journeys (in fiction as well as in life) and am fascinated by their psychological resonances. It's many years now since I was a religious believer, but at some point

during my upbringing that metaphor of the true and false roads obviously

sank

deep.

Two years spent teaching pastoral texts to seventeen-year olds also had its

effect. Some pastoral themes are very similar to those of the expulsion from Eden - nature, lost innocence - and during that time I became aware of pastoral's enduring appeal. Amorous herdsmen may have vanished from Arcadia, but not from Brokeback Mountain. Nymphs bathe al fresco to advertise shampoo and Italian peasants are still

flirtatious at ninety thanks to the simple country goodness of Bertolli

margarine. People who have never heard of the word 'pastoral' still respond to the imagery: we still yearn for that impossible place, the countryside as it never was.

As a result of mulling over these influences, I'm now much

more aware that in my own work, landscape is sometimes in realistic mode, sometimes symbolic (though I hope not anachronistic),

sometimes both, according to the demands of the narrative, while the characters' responses to it are mediated by the ideas by which they interpret the world. Jacob Cullen, the tormented

narrator of As Meat Loves Salt, is

troubled by repetitive nightmares while working the land (a detested job,

perceived by Jacob as futile) in an idealistic Digger commune:

'Often, of late, I flew over Hell and looked down on the

damned, whose punishment it was to mine rocks with picks and spades. They flowed over the black surface like

ants. From time to time a flame would

lick up and burn some of them off. The

rest kept digging.'

His friend Ferris (who conceals a love letter inside a map, something I noticed with

amusement when re-reading the novel) dreams of the same commune becoming not an

Eden (for 'Eden may not be regained') but the next best thing, 'a happy and prosperous Israel.' He reads the landscape in terms of the

opportunities it holds out for freedom and self-determination: not damnation,

but redemption.

In The Wilding,

the shallower and more complacent Jon Dymond congratulates himself on being not

an outsider, but 'a proper village man, woven in': a true countryman, living

the pastoral idyll. His self-satisfaction,

however, cannot last: his Eden carries the seeds

of its own destruction.

In future, when I begin a new piece of writing it will be

with a deepened awareness of my own ways of working with landscape. There are other aspects yet to explore, in

particular why I keep coming back to lost Edens

and find them so resonant. Is there a connection with a traumatic house

move at the age of six? I rarely dream of landscapes but for many years

now, houses where I've lived in the past have made regular appearances in my

dreams. I'd like to unravel that strand

since I suspect there's creative energy bound up in it ― but this blog isn't

the place for doing so.

What are your thoughts on landscape? And is there some important aspect of your

work of which you are now aware, but which wasn't obvious to you at the time of

writing?

I find this whole area very interesting and I think a consideration of a character's environment and how comfortable he is in it can be an important ingredient in fiction. In historical fiction there is the extra dimension of past landscapes. In the later middle ages where I have set Feud, I have used two "landscape" aspects to enhance the characters. One is to create an affinity between the leading character and forests. Forests have an aura, a mystery or sometimes an element of threat or danger. Te second is to contrast in a character's eyes the stark differences between the countryside and the town. Even in the fifteenth century towns like York and, more obviously, London present the characters with a shock because of their size, cramped conditions, etc.

ReplyDeleteLovely thoughtful post Maria. I especially liked the words 'deepened awareness' It took a complete stranger to point out to me that water always features in my books. I haven't worked out the significance of this yet!

ReplyDeleteIt's fascinating. I wonder how all this (forests, cities, countryside)plays out in other cultures, especially outside Europe.

ReplyDeleteReading your comment, Theresa, I was reminded of something Margaret Atwood said (I think it was about The Handmaid's Tale). A stranger had pointed out to her a system of colour symbolism linked with flowers and freedom. She had had no awareness of it while writing.