by Deborah Swift

There is something very appealing about the highwayman’s disguise – the tricorne hat, the cloak, the breeches and boots – and even more so when this disguise is worn by a woman. Contrary to popular belief, records show that there were women who risked the noose, to make their living on England’s rutted and treacherous roads, and who showed their own unique brand of ruthlessness and courage.

Double – Crosser Joan Phillips

Joan was the daughter of a rich and well-established farmer.

Her beauty (and wealth) brought her to the attention of Edward Bracey, a

small-time crook, who planned to seduce her, persuade her to marry him, and

then abscond with her dowry, leaving her flat.

Joan was intelligent enough not to fall for this plan, and

though allowing herself to be seduced, foiled the rest of the plan. Edward

Bracey, according to the Newgate Calendar ‘was very agreeably deceived;

for Joan was as good as he … she consented to rob her father, and go along with

him on the pad; all which she accordingly accomplished.’

So Joan was determined to gain an upper hand, and they never

did marry, but Joan and Edward frequently robbed together on the highway, though

it seems Joan was always the one in control.

Joan had a long criminal career including running an inn, but

eventually, the Law caught up with her and she was arrested in 1685 after robbing

a coach. She was tried under the name Joan Bracey, found guilty, and executed

the same year in Nottingham. Records diverge on how old she was when she died,

some saying she was as young as twenty-one.

Watch a video about her

BBC Criminal Histories "The Highway Woman"https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YnuYdL4TrO4

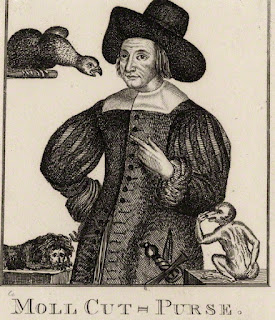

Tudor Highwaywoman Mary Frith

Mary Frith (nickname - Moll Cutpurse) was the daughter of a shoemaker and lived in Aldersgate Street near St Paul’s Cathedral. From an early age she was often in trouble with the law for stealing. To try to reform her, a minister tried to ship her off to New England in America, but Mary dived off the ship and swam back to shore.

From then on, she was arrested frequently for robbery and was held in various prisons - The Old Bridewell, the Compters and Newgate. She was branded on the hand on several occasions – this was a common punishment for thieves. Her stamping ground was St Paul’s Church (now the re-built Cathedral) where she would cut the strings of purses, (hence her nickname) and she also traded as a ‘fence’ for stolen goods and a pimp for younger women. Victims of pickpockets who had lost jewellery or valuables would come to Mary, and she would trade with the criminal underworld to return the items for a cost.

Mary was nearly always dressed as a man, drank in taverns and carried a sword. She is also credited with being the first woman to smoke a long clay pipe. She had a long association with the theatre and by the turn of the century she was performing on stage in men's clothing at the Fortune Theatre. On stage she bantered with the audience, fenced in mock fights, and sang, accompanying herself on the lute.

She was a keen horsewoman and was once bet twenty pounds that she wouldn’t ride from Charing Cross to Shoreditch dressed as a man. Of course she won the bet, and made it all the more entertaining by doing it on Morocco, the most famous performing horse of the day. Her riding skills enabled her to turn highwaywoman during the English Civil War. A staunch Royalist, she robbed the Roundhead general, Sir Thomas Fairfax by holding up his coach on Hounslow Heath.

We know a lot about her because The Life of Mrs Mary Frith of 1662 was one of the first biographies of a female criminal to be published in England and was highly influential in bringing women’s lives to the public interest. It is thought that Defoe’s book, Moll Flanders, was based on her life.

Lady Katherine Ferrers was the inspiration for the 1945 film

The Wicked Lady, starring Margaret Lockwood and James Mason, which tells the

story of a 17th century aristocrat and heiress who turns to highway robbery. Katherine

was supposedly persuaded to a life of crime by her highwayman lover Ralph Chaplin, but he

was caught and hanged on Finchley Common. After his death she worked alone, but

was caught when she held up a coach and shot the driver; unfortunately it was a

trap, and two of the occupants of the coach were armed and shot back. Fatally

wounded, she galloped home to Markyate Manor, where she was found lying on the

front steps - dead, but still dressed as a highwayman.

This of course is not the real story. The real story is one of plunder and possession in The English Civil War, and a time when rural farmers were trying to keep their lands out of the pockets of the aristocrats and were experimenting with new ways of communal living. In my young adult books about the life of Katherine Ferrers I explore these themes, and I enjoyed deconstructing and reconstructing the legend.

Sources:Outlaws and Highwaymen - Gillian Spraggs

The Elizabethan Underworld – Gamini Salvado

Pictures: Wikipedia, East End Women's Museum, Project Gutenberg

Find me and my books on my website www.deborahswift.com