On 31st of this month, a wonderful and rare Ravilious exhibition at the Dulwich Picture Gallery comes to an end. Since this summer is also the 75th anniversary of the Battle of Britain, I hope nobody will mind that I'm revisiting a post which first appeared on my own website early last year.

Eric Ravilious (1903-1942) was probably the best known of the three British Official War Artists who were killed during the Second World War, despite the unofficial hope on the part of Kenneth Clark, who created the scheme, that it would serve to preserve the lives of Britain’s best artists. (Thomas Hennell disappeared in Java in 1945; Albert Richards, who fought as well as painted, was blown up by an enemy mine in Belgium in March the same year.)

This picture, HMS Ark Royal in Action, 1940, is a watercolour made on June 9th from the deck of HMS Highlander and it shows the ship’s anti-aircraft guns at full-blast in the last moments of the Allied withdrawal from Narvik after the fall of France.

Eric Ravilious (1903-1942) was probably the best known of the three British Official War Artists who were killed during the Second World War, despite the unofficial hope on the part of Kenneth Clark, who created the scheme, that it would serve to preserve the lives of Britain’s best artists. (Thomas Hennell disappeared in Java in 1945; Albert Richards, who fought as well as painted, was blown up by an enemy mine in Belgium in March the same year.)

|

| © IWM (Art.IWM ART LD 284) |

In July 1940, the National Gallery mounted its first exhibition of war art, and Ravilious was embarrassed by quite how many of the paintings were by him. He’d taken up the invitation to become an Official War Artist as soon as he was offered it in December 1939, after an autumn spent volunteering with the Observer Corps, watching for enemy aircraft from a post on the top of Sudbury Hill, near his home: “We wear lifeboatmen’s outfits against the weather and tin hats for show. It is like a Boy’s Own Paper story, what with spies and passwords and all manner of nonsense.” (p. 8)

This sense of unreality – the idea almost of playing at soldiers – was remarkably widespread in Britain in that first year of the war, and something I tried hard to capture in That Burning Summer. Equally strong was a sense of growing threat to a particular, pastoral kind of Englishness, a vision of England which Ravilious arguably helped to create. It comes across strongly in the book he illustrated for the Curwen Press book,The Story of the High Street.

In a painting called ‘Observers’ Post’ Ravilious conveys the incongruity of sandbags, duckboards and telephone wires appearing suddenly beside rustic wooden fences and reassuring hedgerows, and under blue skies. His sandbags have a plumped up, pillow-like feel to them, and glow quietly in the last rays of the sun. Another watercolour of 1940, showing Barrage Balloons Outside a British Port is darker, greyer, and the two lone figures at the end of a quay are leaning forward with a greater sense of urgency, but there is a similar tension between the bravely comic whale-shaped monsters (whose accidental escapes Ravilious had frequently sighted from his Observers’ Post) and the reassuringly straight lines of harbour buildings and railings. Meanwhile, the extravagant curve of the quay in the foreground suggests that the land itself is on the verge of becoming as stormy as the sea and sky beyond.

Balloons, ships and aircraft are often given as much, if not more, character than the few people depicted in Ravilious’ war pictures. They come across as plucky creatures. Here, in HMS Glorious in the Arctic, 1940, Hawker Hurricanes and Gloster Gladiators circle the aircraft carrier as they prepare to land on her deck, before leaving Norway.

In the course of his posting to the Royal Navy, Ravilious discovered his fascination with flight. At the Royal Naval Air Station in Dundee he was enthralled by the eccentricities of a lumbering amphibious biplane called a Supermarine Walrus, which could be launched by catapult from a warship, and became very effective in air-sea rescue operations. ’I spend my time drawing seaplanes and now and again they take me up…I do very much enjoy drawing these queer flying machines…what I like about them is that they are comic things with a strong personality like a duck…You put your head out of the window and it is no more windy than a train.’ (p.36)

|

| © IWM (Art.IWM ART LD 1712) |

When Ravilious began his next War Artist contract, it was with the RAF. ‘These planes and pilots are the best things I have come across since this job began. They are sweet and have no nonsense (naval traditional nonsense and animal pride).’ (p38) The luminosity of Ravilious’ watercolour technique was perfectly suited to conveying the peculiar joys of simply being airborne. Over the course of the summer of 1942, he flew regularly in Tiger Moths from a modest airbase in Hertfordshire, at Sawbridgeworth, where the runway was made of coconut matting and living conditions were equally basic. Yet, as it wrote home: ”It was more lovely than words can say flying over the moors and the coast today in an open plane, just floating on great curly clouds and perfectly still and cool . . .” (p. 44)

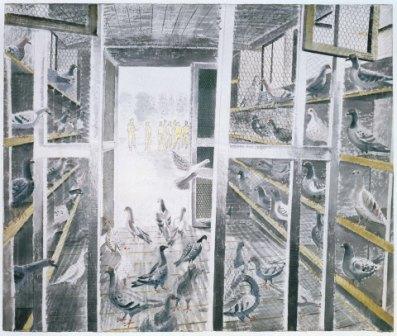

One of my favourite pictures in this book took me back to some of my early research for That Burning Summer. From a long and fascinating conversation with Edward Carpenter, local historian and author of Romney Marsh at War, I confess I stole his story of rescuing a lost homing pigeon, for which – if I remember rightly – he was given a medal. During World War Two, thirty-two pigeons were awarded medals themselves, as James Russell writes in the short essay accompanying this atmospheric watercolour of Corporal Stediford’s Mobile Pigeon Loft. Thousands of lives were saved by birds flying home bearing the co-ordinates of a crash site, and every bomber crew carried one. The pigeons here are full of life and character, with their bright red eyes and distinctive markings. By contrast, the distant group of soldiers who can just be seen through the open doorway are barely there at all. Like the ghostly figures in the painting Morning on the Tarmac, in which sailors or airmen who aren’t even given the solidity of the reflections granted to the aircraft, these men seem on the point of vanishing altogether. Ravilious disappeared himself in Norway on 2nd September. His own plane never returned from a mission to search for survivors after a previous aircraft had gone missing.

(N.B. If you want to see more Ravilious, and are anywhere near Eastbourne, I thoroughly recommend the Towner Gallery's 'behind the scenes' private tours.)

I saw this a couple of weeks ago. My only disappointment was that the very pictures I wanted postcards of were the ones not available in the shop! In fact, I find this is true of every exhibition I go to; why is this?

ReplyDeletehe's a lovely artist, thanks for this Lydia

ReplyDeleteSuch evocative images - thank you!

ReplyDeleteWar artists are near and dear to my heart. I wrote an article on US combat artist, Ed Reep, for AMERICA IN WWII magazine. Thankfully, I was able to correspond with him - he was 92 at the time! - and his daughter helped me out tremendously. He passed away a few years ago, but the autobiography he left of his wartime experiences is amazing to read.

ReplyDeleteI went to see this exhibition a couple of weeks ago and absolutely loved it - and found just the same thing as you, Mary - very frustrating! But thanks for all this extra information, Lydia, and for the thoughts about the paintings - I keep thinking about what it is that makes them so intriguing- and so beautiful.

ReplyDeleteI went yesterday and loved it too - but - same thing! I so wanted a postcard of 'Downs in Winter' and others, but they weren't there. Thanks for all the information and comments. I'm still thinking about what I saw yesterday.

ReplyDelete