|

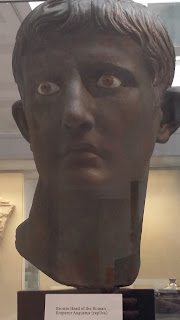

| An example of a Roman Emperor |

Being a Roman Emperor is hard; what with a daily inbox brimming with problems that desperately require solutions; barbarian incursions, military mutinies, revolting provinces, troublesome new religions, failed harvests, plague, inflation, riots - not to mention your own officials plotting behind your back to replace you.

On top of those energy sapping problems an emperor was also expected to do stuff for their people. Easy, I hear you cry, Bread and Circuses! Oh if only it were that easy. Let’s take the circus part of that duo of people pleasers.

The emperor builds a shiny new amphitheatre. If it’s the colosseum it’s taken 10 whole years to complete, a whopping big hugely complex building project that took hundreds of people and oodles of money. This structure is not for the emperor, it’s not a palace where he can kick off his sandals at the end of hard day of emperoring and sink into a comfy couch with a glass of vino and some honey roasted dormice to snack on, it is purely for his people.

You’d think they’d be at least a bit grateful for the effort or at the least the thought. But no! They require more. They want to be entertained and they want the emperor to pay for and stage this entertainment in their shiny new amphitheatre he’s taken 10 years to build for them. And it was not enough to throw a load of gladiators in the arena and tell them to get on with it. Oh no, the people want to see something new from their emperor, something novel, something that nobody had ever seen before, and they want to see it now or else they might riot out their displeasure at your ever so ordinary games.

Even if they are enjoying watching two blind men fight, elephants walking the tightrope and freaking leopards doing kick boxing (that last one is invented, as far as we know, frankly I’m not ruling it out) they will probably make use of being in the same space as the man who makes all the decisions by yelling out why they think those decisions you made stink. This being ancient Rome, a time when poets put pen to papyri to threaten people they didn’t like with the insertion of a radish and a mullet fish in an orifice of their choice and the noble citizen of a seaside down one day paused on his evening walk to scrawl the immortal line ‘I’ve buggered men’ on a wall*, you can bet that such political commentary is likely not going to be terribly polite.

On top of those energy sapping problems an emperor was also expected to do stuff for their people. Easy, I hear you cry, Bread and Circuses! Oh if only it were that easy. Let’s take the circus part of that duo of people pleasers.

The emperor builds a shiny new amphitheatre. If it’s the colosseum it’s taken 10 whole years to complete, a whopping big hugely complex building project that took hundreds of people and oodles of money. This structure is not for the emperor, it’s not a palace where he can kick off his sandals at the end of hard day of emperoring and sink into a comfy couch with a glass of vino and some honey roasted dormice to snack on, it is purely for his people.

You’d think they’d be at least a bit grateful for the effort or at the least the thought. But no! They require more. They want to be entertained and they want the emperor to pay for and stage this entertainment in their shiny new amphitheatre he’s taken 10 years to build for them. And it was not enough to throw a load of gladiators in the arena and tell them to get on with it. Oh no, the people want to see something new from their emperor, something novel, something that nobody had ever seen before, and they want to see it now or else they might riot out their displeasure at your ever so ordinary games.

Even if they are enjoying watching two blind men fight, elephants walking the tightrope and freaking leopards doing kick boxing (that last one is invented, as far as we know, frankly I’m not ruling it out) they will probably make use of being in the same space as the man who makes all the decisions by yelling out why they think those decisions you made stink. This being ancient Rome, a time when poets put pen to papyri to threaten people they didn’t like with the insertion of a radish and a mullet fish in an orifice of their choice and the noble citizen of a seaside down one day paused on his evening walk to scrawl the immortal line ‘I’ve buggered men’ on a wall*, you can bet that such political commentary is likely not going to be terribly polite.

And just to top it off not only did you have to pay for the entertainment of others, provide a suitable level of spectacle and take abuse from the crowd, you also had to look like you were enjoying the thing! Because if you for one small moment look away to sign some official form or the gods forbid take a quick nap you could find yourself publicly scorned or possibly even assassinated!. Witness here Augustus trying to avoid the bloody fate of his adopted father, Julius Caesar.

Oh and did I mention the prizes? Yes, aside from the free novel entertainment and the opportunity to abuse the man at the top, a good emperor tossed prizes into the crowd.

These demands of perfection are applied to every task that an emperor undertakes. Woe betide any that fall a cm short, because they can expect to find themselves in one of the pithier passages in Suetonius’ highly entertaining biographies of the first eleven emperors (and Julius Caesar) or in the case of Claudius here who grievously failed with the Bread part, actual physical danger:

Is it any surprise that Emperors dive at the perks of the role, grasping them in both hands and shed a grateful tear as their name is slapped on a building, a month renamed in their honour and an enormous dish of flamingo tongues and eel spunk* is placed in front of them? Frankly they deserve that eel spunk, let them have it.

However, one Emperor decided he wanted proper appreciation for the job that he’d done and he found a way that ensured that the generally ungrateful Roman public could never forget all the good stuff he had done for them. The route he took to do this was not subtle, but subtlety gets you nowhere in a society where lucky penises are scrawled onto every available surface. His name was Augustus and you’ll have heard of him because he made damn sure he was unforgettable by writing a list of everything he’d done that was marvellous, having it inscribed in massive letters and shipping copies to be put on display throughout the empire.

The Res Gestae Divi Augustus or the deeds of the divine Augustus as it translates, is a list of all the achievements that Rome’s first emperor wanted to be recorded for posterity. It consists of 35 paragraphs, every single one of which translates as ‘I’m brilliant, marvel at it.’

Reading the Res Gestae for the first time is an interesting experience, the boastful tone is at odds with our modern sensibilities where achievements must be downplayed, and we must act humble and grateful when rightfully rewarded. Or at least you do when you’re British. Probably the nearest analogy I can find to the Res Gestae is a job application and that box that asks you to, ‘explain why we should appoint you to the position of xxxx using examples.’ Which you fill in with an account of how you have made a glorious success of every job you've ever held and how much everyone loved you for that, even if you didn’t and they didn’t. But nobody ever got offered a job interview by downplaying their successes or referencing the time they completely cocked up a project.

The Res Gestae is similar in tone. There is no mention of any cock ups in those 35 paragraphs but rather a hugely long list of things he, Augustus, has personally done during his forty odd years in power. He uses ‘I’ 122 times in a text that is only 3861 words long, so he would have been useless at the teamwork question on a job application. But being proactive and working on one’s own initiative Augustus has examples of in spades, as it evident from the opening line of the Res Gestae

A singular sentence that is capable of rendering every reader over 20 feeling instantly inadequate and pondering quite why they spent so much time downing £1 pints of cider in the student union bar when they could have been off championing the liberty of the republic instead.

On keeping the ungrateful people of Rome grateful Augustus is at pains to mention how many times he dipped into his pockets for them:

Now I could work out for you what 300 sesterces times 250,000 people is and then do the same for the subsequent amounts mentioned and then translate this into how many loaves of bread/soldiers/pints of eel spunk that would purchase in total. But I don’t need to, the fact that Augustus mentions it and the number of 0’s that feature demonstrates on its own that Augustus gave away sh*t loads of money to the Roman public. Although it might be handy for you to know that the annual salary of a soldier in this time was around 1200 sesterces per year and soldiers were considered suitably recompensed. Because if they weren’t there tended to be trouble of the pointy sword variety.

In a paragraph dedicated to the Games he staged, Augustus is keen to have noted the efforts he went to in providing entertainments.

I can almost feel him hovering over my shoulder like the ghost of Obi wan Kenobi in Star Wars saying in Alec Guiness' deep voice ‘Be impressed, my child.’ Impressed am I' (accidental Yoda voice).

Other impressive things Augustus is keen to impress upon us include .

I undertook many civil and foreign wars by land and sea throughout the world, and as victor I spared the lives of all citizens who asked for mercy.

He gave his entire attention to the performance, either to avoid the censure to which he realized that his father Caesar had been generally exposed, because he spent his time in reading or answering letters and petitions. Suetonius Life of Augustus.

These demands of perfection are applied to every task that an emperor undertakes. Woe betide any that fall a cm short, because they can expect to find themselves in one of the pithier passages in Suetonius’ highly entertaining biographies of the first eleven emperors (and Julius Caesar) or in the case of Claudius here who grievously failed with the Bread part, actual physical danger:

When there was a scarcity of grain because of long-continued droughts, he was once stopped in the middle of the Forum by a mob and so pelted with abuse and at the same time with pieces of bread, that he was barely able to make his escape to the Palace by a back door.

Suetonius Life of Claudius

|

| The Emperor Claudius having possibly lost his clothes in that mob attack |

Is it any surprise that Emperors dive at the perks of the role, grasping them in both hands and shed a grateful tear as their name is slapped on a building, a month renamed in their honour and an enormous dish of flamingo tongues and eel spunk* is placed in front of them? Frankly they deserve that eel spunk, let them have it.

However, one Emperor decided he wanted proper appreciation for the job that he’d done and he found a way that ensured that the generally ungrateful Roman public could never forget all the good stuff he had done for them. The route he took to do this was not subtle, but subtlety gets you nowhere in a society where lucky penises are scrawled onto every available surface. His name was Augustus and you’ll have heard of him because he made damn sure he was unforgettable by writing a list of everything he’d done that was marvellous, having it inscribed in massive letters and shipping copies to be put on display throughout the empire.

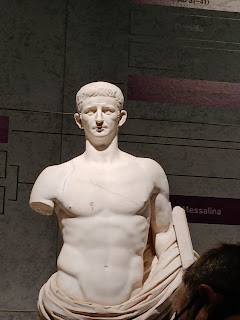

|

| The man himself, Augustus looking damn Imperial |

The Res Gestae Divi Augustus or the deeds of the divine Augustus as it translates, is a list of all the achievements that Rome’s first emperor wanted to be recorded for posterity. It consists of 35 paragraphs, every single one of which translates as ‘I’m brilliant, marvel at it.’

Reading the Res Gestae for the first time is an interesting experience, the boastful tone is at odds with our modern sensibilities where achievements must be downplayed, and we must act humble and grateful when rightfully rewarded. Or at least you do when you’re British. Probably the nearest analogy I can find to the Res Gestae is a job application and that box that asks you to, ‘explain why we should appoint you to the position of xxxx using examples.’ Which you fill in with an account of how you have made a glorious success of every job you've ever held and how much everyone loved you for that, even if you didn’t and they didn’t. But nobody ever got offered a job interview by downplaying their successes or referencing the time they completely cocked up a project.

|

| Amongst Augustus' many talents was directing people to the facilities |

The Res Gestae is similar in tone. There is no mention of any cock ups in those 35 paragraphs but rather a hugely long list of things he, Augustus, has personally done during his forty odd years in power. He uses ‘I’ 122 times in a text that is only 3861 words long, so he would have been useless at the teamwork question on a job application. But being proactive and working on one’s own initiative Augustus has examples of in spades, as it evident from the opening line of the Res Gestae

“At the age of nineteen [44 BC] on my own responsibility and at my own expense I raised an army, with which I successfully championed the liberty of the republic when it was oppressed by the tyranny of a faction.”

A singular sentence that is capable of rendering every reader over 20 feeling instantly inadequate and pondering quite why they spent so much time downing £1 pints of cider in the student union bar when they could have been off championing the liberty of the republic instead.

On keeping the ungrateful people of Rome grateful Augustus is at pains to mention how many times he dipped into his pockets for them:

To each member of the Roman plebs I paid under my father's will 300 sesterces and in my own name I gave them 400 each from the booty of war in my fifth consulship, and once again in my tenth consulship I paid out 400 sesterces as a largesse to each man from my own patrimony, and in my eleventh consulship I bought grain with my own money and distributed twelve rations apiece, and in the twelfth year of my tribunician power I gave every man 400 sesterces for the third time. These largesses of mine never reached fewer than 250,000 persons.

Now I could work out for you what 300 sesterces times 250,000 people is and then do the same for the subsequent amounts mentioned and then translate this into how many loaves of bread/soldiers/pints of eel spunk that would purchase in total. But I don’t need to, the fact that Augustus mentions it and the number of 0’s that feature demonstrates on its own that Augustus gave away sh*t loads of money to the Roman public. Although it might be handy for you to know that the annual salary of a soldier in this time was around 1200 sesterces per year and soldiers were considered suitably recompensed. Because if they weren’t there tended to be trouble of the pointy sword variety.

|

| Yet another thing Augustus was brilliant at - obedience training wild boars |

In a paragraph dedicated to the Games he staged, Augustus is keen to have noted the efforts he went to in providing entertainments.

I gave beast-hunts of African beasts in my own name or in that of my sons and grandsons in the circus or forum or amphitheater on twenty-six occasions, on which about 3,500 beasts were destroyed. I produced a naval battle as a show for the people at the place across the Tiber now occupied by the grove of the Caesars, where a site 1,800 feet long and 1,200 broad was excavated. There thirty beaked triremes or biremes and still more smaller vessels were joined in battle. About 3,000 men, besides the rowers, fought in these fleets

I can almost feel him hovering over my shoulder like the ghost of Obi wan Kenobi in Star Wars saying in Alec Guiness' deep voice ‘Be impressed, my child.’ Impressed am I' (accidental Yoda voice).

|

| Augustus with that far more succinct first draft of the Res Gestae |

Other impressive things Augustus is keen to impress upon us include .

I undertook many civil and foreign wars by land and sea throughout the world, and as victor I spared the lives of all citizens who asked for mercy.

Bless you, Imperial Majesty

I restored the Capitol and the theatre of Pompey, both works at great expense without inscribing my own name on either.

I restored the Capitol and the theatre of Pompey, both works at great expense without inscribing my own name on either.

Unexpectantly restrained of you, Imperial Majesty

The door-posts of my house were publicly wreathed with bay leaves and a civic crown was fixed over my door and a golden shield was set in the Curia Julia, which, as attested by the inscription thereon, was given me by the senate and people of Rome on account of my courage, clemency, justice and piety.

The door-posts of my house were publicly wreathed with bay leaves and a civic crown was fixed over my door and a golden shield was set in the Curia Julia, which, as attested by the inscription thereon, was given me by the senate and people of Rome on account of my courage, clemency, justice and piety.

Humble much, Imperial Majesty?

I made the sea peaceful and freed it of pirates.

I made the sea peaceful and freed it of pirates.

Ooo ahhh, Imperial Majesty

And my all time favourite: After this time I excelled all in influence, although I possessed no more official power than others who were my colleagues in the several magistracies.

And my all time favourite: After this time I excelled all in influence, although I possessed no more official power than others who were my colleagues in the several magistracies.

Of course you didn’t Imperial Majesty whom I am calling Imperial Majesty because I want to of my own free will.

The Res Gestae as well as being a document to big up one man (and by the gods it does that!) also acts as a blueprint for what a good emperor should be; they should be generous to the people, build a ton of stuff, secure Rome’s frontiers & conquer new lands, be mindful of religion and paying respect to the gods, take care to reward the army and put on fabulous entertainments.

All of which sounds bloody exhausting, someone pass the roasted dormice please!

The Res Gestae as well as being a document to big up one man (and by the gods it does that!) also acts as a blueprint for what a good emperor should be; they should be generous to the people, build a ton of stuff, secure Rome’s frontiers & conquer new lands, be mindful of religion and paying respect to the gods, take care to reward the army and put on fabulous entertainments.

All of which sounds bloody exhausting, someone pass the roasted dormice please!

* The poet here is Catullus who has the reputation for writing an opening line to a poem so filthy it wasn't translated into English until the 20th century, 2000 years after it was written.

* A favourite dish of the Emperor Vitellius, it is referred to in our sources by the far nicer sounding milt of lampreys.

L.J. Trafford is the author of many books about Ancient Rome, she just can't stop writing them. Amongst her titles are How to Survive in Ancient Rome a guide for the would be time traveller to the year 95 CE and Sex and Sexuality in Ancient Rome a guide for people interested in that sort of thing.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.