Yet one famous woman of early Rome did hold power. Her name was Tanaquil. She was not Roman, but Etruscan. And she did not gain fame for dying but for being a prophetess and a queen.

Tanaquil was an Etruscan noblewoman from the city of Tarquinia. Her husband, Lucumo, was the son of an immigrant Greek. Tanaquil knew Lucumo would not gain power in her city because of this and so she convinced him to travel to Rome to seek his fortune. As their carriage ascended the Janiculum Hill, an eagle swooped down and snatched Lucumo’s cap carrying it aloft before once again replacing it on his head. Skilled as a seer, Tanaquil predicted that, as the bird had flown from the direction of Rome and taken the cap from the crown of Lucumo’s head, her husband was destined for greatness.

On arrival in Rome Lucumo became friend to the king, Ancus Marcius, as well as

guardian to his children. When Marcius died before his children were old enough

to take the throne, Lucumo was elected to be king by the Romans and changed his

name to a Latin one – Lucius Tarquinius Priscus. He was to be the first of

three Etruscan kings who ruled Rome before the third, Tarquinius Superbus, was

expelled after the rape of Lucretia.

So could the myth of a prophetess such as Tanaquil be based

in fact? The Etruscans were indeed skilled in the art of foretelling the future

from the flight of birds. And there is evidence from funerary art and tomb

inscriptions that Etruscan

women may well have been priestesses of high standing. The Roman author,

Livy, who tells us Tanaquil’s tale, does not question her ability. In fact he

writes that her powers of prophesy proved correct again when she saw a slave

boy called Servius Tullius asleep with a blue flame burning above his head.

Tanaquil predicted that he would also rule Rome. When Lucumo was murdered,

Tanaquil cemented her own power by supporting Servius Tullius in being

appointed the monarch. He in turn was to become one of the greatest and

most just Kings of Rome (but that is another story…)

Vel Saties

As mentioned, the Etruscans observed

the flight of birds for the purposes of divination. The process of interpreting

the patterns of flight was known as taking the auspices (literally ‘looking at

birds’). As

was the case with understanding lightning portents, the sector of the sky

where a bird flew was a determining factor to interpret the will of the gods

based on the quadrant in which the relevant deity resided. The type of bird was

also important. Doves transmitted messages from Turan (Aphrodite/Venus) whereas

the king of the gods, Tinia (Jupiter/Zeus), used an eagle.

The Romans relied heavily on the act of auspication, too. It was an essential part of the politics of Rome. Before any decision of State was made, omens were observed through the flight of birds. This sometimes involved an augur releasing a flock of birds and watching whether they flew to the right or left. The term ‘sinister’ derives from sinistra the latin word for ‘left’ as it was considered an ill omen if the birds flew in that direction. Negative connotations of being left handed have continued for centuries and may well have stemmed from this concept.

In Rome the different bird calls of ravens, crows, owls and chickens were also used to identify divine will. The flight of eagles, vultures and woodpeckers all had significance too. The eating patterns of chickens were also observed. It was considered ill luck if, once released from a cage, the hens baulked at eating the proffered bread. I presume this form of divination allowed for some human manipulation of results!

The founding of Rome itself was based on auspication. When the two feuding

brothers, Romulus and Remus, could not agree on the site upon which the city

was to be built, they decided to test their abilities as augurs. Romulus saw

twelve vultures settle on the Palatine Hill while Remus saw only six alight

upon the Aventine. An interesting way to settle an argument.

What is fascinating about Tanaquil is the fact she was, in every way, a player rather than a victim. As a queen and seer, she was instrumental in establishing and continuing the reigns of the Etruscan kings over the Romans. Her ambitions became those of the men she influenced. Unlike Lucretia and Virginia who were controlled by men and whose fate was to die for Rome, Tanaquil moulded destiny to her purpose. And strangely, whereas Etruscan women were usually criticised as wicked and corrupt by the Romans due to the freedoms afforded to them, Tanaquil was not reviled but revered. There are some who posit that she was later deified as a Roman Goddess of Fire, the Hearth, Healing and Women.

The image of Tanaquil was painted by Domenico

Beccafumi, (1486 – May 18, 1551) an Italian Renaissance – Mannerist painter who

was a representative of the Sienese school of painting. This is apt as Siena

was one of the cities of ancient Etruria.

The image of Vel Saties is from the Francois Tomb in Vulci, Italy (circa 330BCE). It depicts the aristocratic wreathed with laurel and wrapped in a lavish purple cloak bordered with scrolls and embroidered with nude male figures holding shields. The Etruscan is observing a woodpecker in flight while his servant, Arnza, holds a female woodpecker attached by a string to attract the bird back. The woodpecker was sacred to the god of war Laran (Ares/Mars), and it is likely that Vel Saties was consulting the deity before a military encounter. Images are courtesy Wikipedia Commons

Elisabeth Storrs is the author of the A Tale of Ancient Rome saga, and the founder of the Historical Novel Society Australasia. She has also written a short story based on the Lucretia legend which can be obtained at her website www.elisabethstorrs.com

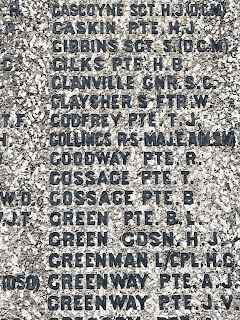

.jpg)