Music has always had the power to move us in ways we find both sentimental and stirring. Throughout history, armies have gone into battle to the dramatic accompaniment of musicians, the sound meant to arouse the soldiers and put fear into the enemy. The bagpipes and beating drums at the Battle of Culloden are one such example. Military bands during WWI also spring to mind, and when not on the battlefield, ballads - both patriotic and sentimental - were created to keep the glories of battle alive. The human voice too, has the power to stir us, e.g. the trilling sound known as Zaghareet, or Ululation, used by the Arabs and which dates back to the pre-Islamic era. In addition to the drumbeat, this ululation stimulated excitement on the battlefield.

WWII was no different, but unlike WWI, radio was the cheapest form of

entertainment, and it was the most popular medium during those dark days. The

accessibility and availability of radios meant they fueled propaganda and could

reach a vast number of citizens. Radio helped entertain and inform the

population, encouraging citizens to join in the war effort. German propaganda

minister, Joseph Goebbels, called the radio the “eighth great power”, noting

the influence of radio in promoting the Third Reich, and approved a mandate in

which millions of cheap radio sets were subsidized by the government and

distributed to citizens.

Britain’s wartime government created the Council for the Encouragement of Music

and the Arts in 1940 to promote musical activity on the home front, while the

Entertainments National Service Association (ENSA) brought a range of concerts

and live music to the troops at home and overseas.

The BBC quickly realised that listening to radio newscasts about the war was not enough and saw one of its main wartime missions as nurturing civilian morale, and “taking people away from thinking about the war”. Plus there were thousands of men and women working in civilian defense bases, such as anti-aircraft batteries, with many millions more working in factories. One woman’s diary entry for 9 April 1940, in the midst of the Norwegian campaign: read, “I felt so nervy and jumpy after tea – could not settle – I kept turning the wireless to see if there was a news bulletin anywhere in English – not German – and wondering if our sailors were winning in the reported sea battle.” In contrast, Adelaide Poole, a diarist in Sussex, avoided listening to the news at all, because she believed it was responsible for the premature death of her own sister in the United States.

Light

entertainment, especially music, became extraordinarily powerful at motivating

people and the programs soon expanded. Archives reveal how the BBC actively aided the

resistance during the Second World War, partly by sending coded messages in

music. However, because of the secrecy of

the message in the music, things sometimes went wrong. “The studio engineers might look for a record, see a scratch, or they

don't like it, or they think it's not the appropriate mood for the occasion —

and they play a different recording”. This kind of thing meant if the wrong

piece of music was played, then quite possibly the wrong bridge was blown up. Studio

engineers were not privy to this secret information, and it was the job of BBC staffer, Alec Sutherland, who oversaw the program,

therefore, to sit in the studio and to shout at them and say, "I don't care if you think there's a scratch

on it or it's not very good. That is the track that has to be played."

Music While You Work

Music While You Work, a program specifically designed to

relieve the monotony of production line working became very popular. Famous

bands toured hundreds of factories, playing light music at 10.30am and 3pm -

the times of day when workers' concentration dipped. A 10.30pm show was also

put on for night shift workers. The

program’s signature tune was, Eric Coates’ quick-march 'Calling All Workers': The BBC’s basic principles of Music While You Work, were that it should always offer music that

was ‘unobtrusive’, ‘monotonous’, yet always ‘cheerful’ – and ignore ‘subtlety’

and ‘artistic value’.

As the war progressed and the

V for Victory sign became common, the BBC used the first few bars of

Beethoven’s 5th Symphony, as it had the same rhythm as the Morse for

the letter ‘V’. The Nazis

were enraged but in the end, recognizing that they couldn't win, adopted it as

their own, putting a V on the Eiffel Tower, and renaming one of Prague's main

thoroughfares Victoria Street. But what of

other music? "Lili Marlene" became the most popular song of

World War II with both German and British forces. Based on a German poem, the song was recorded

in German, English, and Italian. Joseph Goebbels hated the song and

promptly banned it, but it eventually made the airways, and by the time Rommel

landed in North Africa, the song was being played over Radio Belgrade in Nazi-occupied Yugoslavia. Because of its popularity, Rommel always began his broadcast with it. It became a

hit. “Lili Marlene” was a poem set to

music in 1938. The British Troops in the North Africa Campaign also started to enjoy the song; so much so that it was quickly

translated into English. The song was used throughout the war as a propaganda

tool. In German, Lale Anderson’s was the most favoured, while in English, there

were versions by Vera Lynn and Anne Shelton,

but it is mostly remembered now by Marlene Dietrich, who sang it in both English

and German. It was also a hit in French and Italian.

When America entered the war, the U.S. Army began broadcasting from London during World using equipment and studio facilities borrowed from the BBC. Fearing competition for civilian audiences, the BBC initially tried to impose restrictions on AFN broadcasts within Britain. Nevertheless, AFN programs were widely enjoyed by the British civilian listeners who could receive them, and once AFN operations transferred to Europe (shortly after D-Day) AFN was able to broadcast with little restriction with programs available to civilian audiences across most of Europe, (including Britain), after dark.

As D-Day approached, the network joined with the BBC and the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation to develop programs, especially for the Allied Expeditionary Forces. Mobile stations, complete with personnel, broadcasting equipment, and a record library, were deployed to broadcast music and news to troops in the field. During the dark days and nights on the home front and abroad, songs from both sides of the Atlantic encouraged people onto the dance floor and lifted spirits. It was songs like the following that kept people going.

"The White Cliffs of Dover" was recorded in 1941 by Glenn Miller & His Orchestra, but it was Vera Lynn’s 1942 recording that captured the hearts of listeners.

"We’ll Meet Again" (1939) Vera Lynn

“There'll Always

Be An England” Vera Lynn.

"Run, Rabbit, Run" (1939) Flanagan and Allen

"Everything Stops For Tea" (1935) Jack Buchanan

‘Goodnight Sweetheart’ was recorded by several artists including Kitty Carlisle and Jerry Wayne.

"We’re Going to Hang Out the Washing on the Siegfried Line" (1939) It was recorded often during WW2, with notable recordings by Flanagan & Allen, Arthur Askey, and Vera Lynn.

‘When The Lights Go On Again (All Over

The World)’ (1943) Vaughan Monroe & His

Orchestra: Vera Lynn

“God Bless America” was the first patriotic war song of WWII in the U.S. Written by Irving Berlin for a WWI wartime revue, it was withheld and later revised and used in WWII.

‘As Time Goes By’ (1931) made famous over a decade later by the film Casablanca (1942).

Rudi Vallee’s version remained the most popular

“What a Diff'rence a Day Made"

- Andy Russell with Paul Weston & His Orchestra (1944)

"When The Lights Go On Again

(All Over The World)" - Vaughn

Monroe & His Orchestra (1943)

You'd Be So Nice To Come Home

To - Composer: Cole Porter - From the musical Something to

Shout About – (1943)

"Yours" - Jimmy

Dorsey & His Orchestra

‘Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy’ (1941) The Andrews Sisters

‘In the Mood’ (1930/38) Glenn Miller and his

Orchestra.

"Don't Fence Me

In" - Bing Crosby and The Andrews Sisters

"Don't Get Around

Much Anymore” (Never No Lament)" - Duke

Ellington & His Orchestra

"Don't Sit Under

The Apple Tree” (With Anyone Else But

Me)" - Composer: Lew Brown, Sam

H. Stept, and Charlie Tobias (1942)

"Ev'ry Time We Say Goodbye"

- Composer: Cole Porter - From the musical Seven Lively Arts (1944)

"Lili Marlene" Hildegarde

France

Being under Occupation, France also had its Resistance songs such as the Marseillaise and The Song of the Partisans, and the most popular songs were also sung in German, English, and Italian.

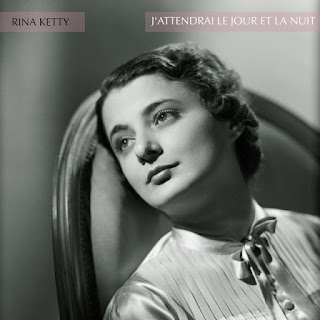

“J'attendrai” ("I will wait") Recorded by

Rina Ketty in 1938, became the big French song during World War II. It is a French

version of the Italian song Tornerai (“You Will

Return”) The German version was equally as popular.

“Nuages” Django Reinhardt

“J'ai chanté sur ma peine” Lucienne Delyle

“La Romance de Paris” Charles Trenet

“Seule ce soir” Leo Marjane

“Où sont-ils mes petits copains?” Edith Piaf

“Ca set ci bon” Maurice Chevalier

“Lili Marlene” Suzi Solidor

“Dans le chemin du

retour” Raymond Legrand et son

Orchestre – Irène Trèbert

French composer, Olivier Messiaen, wrote his ‘Quatuor pour la fin du temps’ (Quartet for the End of Time) when he was a prisoner of war in a German camp in 1940. Messiaen was 31 years old when France entered WWII and was captured shortly after by German forces. He was imprisoned in a prisoner-of-war camp in Görlitz, Germany (now Zgorzelec, Poland). The powerful piece of chamber music was premiered by Messiaen’s fellow prisoners in the camp – on ruined instruments. Messiaen later said of the performance: “Never was I listened to with such rapt attention and comprehension”

Italian Partisans

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zyh_OVeQZH0

Italy

WWII produced many songs of propaganda suitable for radio broadcasts, and like other countries, it was Lili Marlene that made a big impression. However, in Italy, it was primarily the Resistance that originated a vast songbook opposing the regime.

“Bella Ciao” A mixture of peasant folklore, artisan tradition, popular

songs, and urban ballads, would survive in the golden age of protest songs along

with the vast Alpine song repertoire.

“Lilli Marlene” Orchestra

della Canzone A. Angelini Lina Termini

“Caro papa”· Jone Cacciagli con Orchestra

di Carlo Zeme

“Sole

d'Italia” Francesco Albanese e

coro

“Ninna nanna grigioverde” Gianna Pederzini

Rosita Serrano

Germany

There were songs written specifically for the Nazi Party, and much older German patriotic songs from before WWI that have become associated with them. Das Lied der Deutschen ("The Song of the Germans") is one of them. It was written in 1841 and became the national anthem of the Weimar Republic in 1922. During the Nazi era, only the first stanza was used, followed by the SA song "Horst-Wessel-Lied". Many of the Nazi Songs were marches and are banned in Germany today.

“Deutschland Erwache” also known by its original name, Heil Hitler

Dir ("Hail Hitler to Thee"), otherwise known as Sachsenmarsch der NSDAP, was written

by NSDAP member Bruno C. Schestak and premiered in the celebrations of Hitler's

48th birthday on 20 April 1937.

“Erika” is A marching song used by the

German military. It was composed by Herms Niel in the 1930s and soon came into usage by the Wehrmacht. No other marching song during WWII reached the popularity of Erika.

“Komm Zuruck” Rudi

Schuricke

“Hm hm, Du bist so zauberhaft” Rudi Schuricke & Hans

Carste and his Orchestra.

“Einmal wirst Du wieder bei mir sein” Rudi Schuricke

“Bei Dir war es immer so schön” Rosita Serrano

“Schön ist die Welt” Hans Carste and his Orchestra.

“Vim Schlager” Lotte Werkmeister.

“Ich tanz’ Fräulein Dolly Swing”- Fritz Weber & his

Dance Orchestra.

“Jawohl, meine Herrn” Die Goldene Sieben.

"Lili Marlene" Lale Anderson

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KIc9kddJT6M

German mother with her children listening to a Volksempfanger receiver

Mark Bernes perform "Dark is the Night" in 1943

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HjmmxX5U2VM

The Soviet Union

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n9oQEa-d5rU

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wEL0RL_bBkw

Sofia Vembo

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l8JzuSXs0GU

Greece

At first, Greece had to contend with the Italians and won. Unfortunately, The Germans came to their aid. Therefore many Greek songs are directed at either the Italians or both. Important musicians at the time wrote wonderful songs. Sofia Vembo, known as the “Songstress of Victory, and a great singer of love songs during the ’30s and 40s, sang songs that rallied the soul of the Greek people.

“Children of Greece, Children,” by Sofia Vembo, was written after the Italian attack on Greece, on 28. October 1940. This famous song encouraged the Greek soldiers during the Greek-Italian Wars.

“The Song of Freedom” Sofia Vembo

“How I’m sorry” Sofia Vembo

“I love you and I like the life” Sofia Vembo

“Mussolini, allaksa gnomi” (Mussolini, I Changed My

Mind) Markos Vamvakaris

“An fygoume ston polemo” (If we go to war) Markos

Vamvakaris

‘I’m not afraid of the Centaurs” Bagianderas.

%20listens%20as%20Wagnerian%20conductor,%20Dr.%20C.%20Muck,%20leads%20the%20Leipzig%20Orchestra..jpg)