I have just had

the privilege and honour of teaching a week-long Arvon course at Lumb Bank with Emma

Darwin and Rob Low as co-tutors. For

those of you who haven’t

been, the location is Ted Hughes' house on the vertiginous side of an

outstanding Yorkshire vale and the staff, as always at Arvon

centres, are fantastic. We had 15

inspired and inspiring students and I have no doubt there’ll be a clutch of

novels in about a year’s time that will have grown from the seeds we sowed.

|

| The View from the back door at Lumb Bank (mcs) |

Part way through

the week, it became apparent that we needed a ‘how to write battle scenes’

seminar that was not part of the planned teaching: not everyone wanted it, but

those who did, wanted it very badly (Emma did the ‘how to write sex’ seminar: I

leave the recollection of that to her).

So having thought

about battles enough to teach a dozen people, I thought it might be worth

reprising that here.

Plainly,

any battle scene is constrained by the era and location of the novel

and it would be impossible to cover all the bases, but there are a few

rules of thumb, the first and

most obvious of which is that every novel must be character-led.

Thus any

battle in which our primary protagonist(s) engage must in some way move her or his

narrative arc forward. There are authors

for whom battles are simply a blood fest, but they are relatively rare and

their books are generally (to my mind) unreadable. In the same way that dialogue grows out of

our characters and strives always to reveal more, enabling the reader to get

under their skins, so must a battle bring us deeper, closer, into more intimate

relationship with our characters.

| Pictish battle scene from Aberlemno churchyard by 'Greenshed' |

In pure fiction,

this is relatively straightforward – when I needed to show Bán, the brother of

the girl who became the Boudica, as a youth, growing towards adulthood, and

needed to show how battle changed him, it was relatively straightforward to

create a battle of suitable size in a location that worked.

This becomes

harder when we’re writing about historical figures – Boudica, say, or Jeanne

d’Arc, or Vespasian – then we know when and where the battles took place, and

who won them: so the challenge for the author is to find the characters who fit

this pattern, and find how each battle helps them to grow into themselves,

helps them become more sophisticated as people… or not. If our character exhibits a courage

heretofore unknown, it might be interesting. If our character exhibits a lack

of courage, or a bloodlust, or a slyness that was heretofore unknown, it might

well be fascinating.

Thus we need to

know the why of a battle before we write the where and the who and the how.

After that, the choreography comes naturally.

It must be grounded in reality: I stop reading a book at the point where

a legionary with a gladius makes a huge roundhouse swing and cuts off his

opponent’s head - or the more modern

equivalent. Yes, it is possible to

decapitate your enemy: the Samurai do it.

The indigenous Maya were supposed to have an obsidian-edged club, the

macuahuitl, which could decapitate a horse (!)

- but a gladius is not that, and anyone on the average battlefield who

opens him or herself up wide enough to make that kind of a stroke is going to take

a blade in the gut/throat/armpit long before any decapitating happens.

|

| Bayeux Tapestry Scene 57 |

As with any other

aspect of historical writing, you need

to have done your research. To write good battles, you need to have a good

grasp of battlefield tactics and the strategies of war. It helps to have spent

some time in battle re-enactment if only to gain an insight into the churn of

emotions that sing through a battle.

Battles are fun –

but only if you are rested, fed, watered, clothed, adequately armed and think

you have some chance of winning; otherwise, they are somewhere between a duty

and a nightmare. But in all cases,

battles exist on the cusp of life and death; at that point where, as Handsome

Lake said, the boundary between the lands of the living and the lands of the

dead is no thicker than a maple leaf.

This is life in the raw: whatever masks a character might raise to keep

him or herself safe in their current social construct, these masks fall away

when we need to react in the moment without forethought. So battles let us see

people as they really are.

|

| Battle of Marston Moor 1644 |

In terms of

distance, as a writer, you may need to be able to take the distant – eagle’s

eye – view as well as the up-close, personal, blood-in-the-eye of a spear

wound, a bash with a shield edge, a blade stabbed out and twisted. If you

aren’t a re-enactor (and sometimes even if you are) you need to have read a

great many first hand accounts of the era you’re working in – with the coda

that any man who writes of his own

battles almost always inflates the nature of his part in the fighting. When I fought as part of an Anglo-Saxon

battle group, we were told that the word for ‘shield’ meant ‘spear

trapper’ - which says a lot about the

tactics and the battlefield dynamic. Shield walls need to remain solid: break them

up and you have a series of single combats, which may sound heroic, but the

truth of a battlefield is that someone else will come along and stab you in the

back as soon as you give all your attention to one person and stop being fully

aware of all that’s around you. The

dynamic is different if there are archers, or crossbows, or muskets (or any

modern firearm) on the field; it’s not enough, then, to be aware of the people

around you.

|

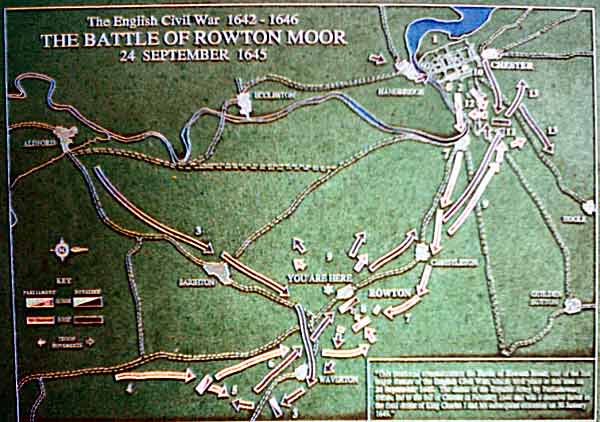

| Rowston Moor battle plan (by Chester tourism.) |

To write anything

bigger than a single one-on-one fight, you, the author, need to understand the

strategy of your battle and its place in the larger war (if there is one), so

that you can manoeuvre blocks of infantry/cavalry/whatever across a battlefield

with some idea of where they want to go. It can be useful to switch between a far

distant ‘eagle’s eye’ or hilltop, or other broad-brush view, in to the shifting

of companies or centuries or squadrons and then closer in to the actual cut and

thrust. These switches don’t have to be

linear and they don’t have to follow a sequence, but we-as-reader need to be

anchored in some kind of geographical reality if we are to have any chance of

understanding what’s going on.

|

| Agincourt 1415 |

Last, be aware

that we are indoctrinated by television and the movies and real life isn’t like

that: not only do most people not decapitate their opponents in a single

move, they often don’t slice off limbs, bite off fingers, or kill a hundred

people without receiving any wounds (Terminator, anyone?). They also – and this

is more important – can’t fight for long if they’re leaking blood from a dozen

major incisions and have at least two structural skeletal fractures. Our tendency to a) enhance the damage and b)

enhance our character’s capacity is what kicks us into the realm of

fantasy. And there’s nothing wrong with

fantasy; we just need to know that’s where we’re going.

I left the

students with a reading list of the authors and novels in which there are some

absolutely outstanding historical battles. It’s not exhaustive by any means,

but any of these is a good starting point:

Mary Renault’s ‘Fire from Heaven’, Dorothy Dunnett’s King Hereafter,

Robert Wilton’s ‘Traitor’s Field’, 'Into the Valley of Death' by History Girl, AL Berridge (all her work is first class and well worth reading) - and Robert Low: just about everything from

the Oathsworn to the Kingdom series and beyond. You can’t go far wrong with

these.

10 comments:

This is brilliant! Thanks so much for sharing, Manda. I'm just about to tackle a battle scene based on a passage in Virgil and you've given me some useful tips.

Excellent blueprint for success! I think your point about research - knowing how the weapons were used and what sort of "damage" might be expected - is vital for an actual historical battle. The other thing, if it's possible, is to visit the site. I've found that has helped me enormously. Historical sites have usually changed but some still allow you to put yourself in the position of the combatants and get a feel for their perspective in relation to the contours, position of rivers and other features, etc.

Fantastically helpful, Manda! I have do not (another) sea battle next year so shall use this as my guide.

And I would add Into the Valley of Death by our own HG Louise Berridge, which I have just read and loved.

Oh, yes! AL Berridge - wonderful, wonderful writer of battles. I'll add that... thank you

Glad you all liked it

m

Wonderful... Makes me want to write more battle scenes!

At least one battle happens in every book I've published, though many of these are for young readers, which presents a special challenge - how to depict a battle with the outcome suitable for 9 year olds?

So far, I've had the most fun with my older Alexander the Great novel, where I got to write battles from the horse's viewpoint. These were historical, and so the outcome was known (i.e. Alexander won all of them except the last one against Prince Porus' elephants in India). But the unknown fates of the minor characters and their horses still left me with enough creative freedom to make the book interesting to write. I even ended up with my own theory of the Battle at the Granicus, since that one (early in Alexander's campaign) was obviously the subject of careful propaganda to make Alexander look more of a hero than he acted on the day.

With historical battles, I think the main thing to remember is that history is written by the victors, and there is always another point of view... that's what makes battles so interesting!

Good post - and yes, I think a "writing battles" course sounds great.

Writing a battle for that age group is quite tricky. They aren't squeamish, particularly after what they see on TV regularly, but on the other hand the brutal reality would be too much.

Not too much detail, I'd say, and yet not the bloodless kind of glamourisation approach.

Excellent… so much good information here. Should be read and noted by anybody who writes about battles.

Another thing often overestimated by writers (fiction and non-fiction) on battles is the actual desire of participants to kill each other. A good way to get the”feel” of a battle – at any rate one where the bulk of the combatants are not professional soldiers – is to watch some film footage of a riot. You see a great deal of rushing around, a lot of sound and fury, but notice how few there actually take the initiative in attacking the opposition…

Same in battle, at least until the present day when soldiers are indoctrinated to fight and kill. In World War II, only about 30% of conscript combatants actually fired aimed shots at the enemy, unless they felt personally threatened .

Similar story in earlier conflicts, apart from the warrior elite who often made up only a small proportion of an army. The famous “Highland Charge” of the Scottish clans for example. The actual fighting was mainly done by the chiefs and their immedate retainers in the front line. The rest, unkindly described by an an 18th century English general as “arrant scum”, hung around behind, and tended not to really get involved unless the opposition routed, when they would readily join in the killing and looting. There is , it seems, an almost atavistic urge to kill a fleeing opponent… A number of likely reasons for that.

At Culloden, for example, when faced by disciplined troops who kept up a steady fire, the "Charge", without at all belittling the men and boys caught up in a hellish situation, on a number of occasions became more of a "Highland Shuffle".

So basically, and this is as important a consideration for non-fiction writers as novelists,when writing about a battle don’t necessarily believe all the blood and thunder boasts you sometimes read about from actual or alleged participants. To be charitable, the human memory can play tricks .

As for beheading with a single stroke, try it with a dead sheep and a 17th century (replica) cavalry sword sometime…. If you can do it, you’re a better swordsman than I ever was:-)

I practise Chinese broadsword as part of my tai chi practice, It is a fun thing to do as a sport, but a really scary weapon if you were using a real one, in a battle, It's a kind of scimitar, and probably could be used to decapitate if a person put their mind to it, but, as you say, the soldier is in the business of selling their lives as dearly as possible and neat decapitations are not the object. Wholesale butchery is more likely the scenario. I do agree with you about the unlikeliness of so many fictional scenarios where people fight on - though I suspect people can do things when angry and psyched up that they couldn't do at other times. All the same, I adore V.I. Warshawski, but when she rises from her sickbed, with a fracture or other injury that would incapacitate normal people, goes off to the empty factory or wherever, and engages with the baddies, I do always feel rather impatient. I have decided though that this must have something to do with psychodrama, where the hero becomes the image of ourselves keeping going even though we think we couldn't possibly, or encourages us to do so?

When I say wholesale butchery, I meant really, messy butchery!

Post a Comment