Regular readers of this blog will probably be familiar with Louise Michel, teacher, poet and revolutionary heroine of the 1871 Paris Commune, but she’s not exactly a well-known figure in the English-speaking world. Yet. If The Red Virgin and the Vision of Utopia, the new graphic biography by Mary M. Talbot and Bryan Talbot, has anything like the success of their remarkable first collaboration, Dotter of Her Father’s Eyes – and it certainly deserves to – this could be about to change.

Michel is hardly obscure. In fact she’s legendary. She’s iconic. In France (and indeed New Caledonia) there have been schools and streets and squares named after her, not to mention two International Brigade battalions and a Metro station. She romanticised her own life in her memoirs, and has been mythologised ever since. She was a saint, but a trying one, as an imagined contemporary in The Red Virgin and the Vision of Utopia admits. By embedding her biography within not one but two other narratives, the Talbots subtly acknowledge all this and simultaneously reframe Michel in an entirely new way. She emerges as an inspiring if imperfect visionary, whose utopian dreams and desires for a more perfect world might actually, by implication, be one day within our reach.

I won’t give away its surprising outer envelope, but the main story begins with Michel’s death, and the arrival of her coffin at the Gare de Lyon in Paris on January 22nd 1905. Michel’s formidable face is framed by a wreath of red carnations, but she’s not named, and the reader is left to work out why crowds are gathering, and red flags flying. As the cortège leaves the station, in a scene which manages to look both forwards and back to the proclamation of the Commune at the Hôtel de Ville on March 26th 1871, we see a young woman holding up a sign for Mrs Charlotte Perkins Gilman. America’s famous feminist is on a European lecture tour. Michel’s story will emerge in conversation between Gilman and Monique, the daughter of fellow revolutionary who stood on the barricades with Michel. A little later, the unnamed one-eyed Communarde joins them.

The double narrative hinges on an imagined meeting in London. As far as I’m aware, Gilman only once encountered Michel and her fellow anarchists, Kropotkin and Reclus (‘desperately earnest souls’), at the alternative meeting arranged in London 1896 after the anarchists had been banned from the International Socialist and Labour Congress. She was impatient with what she perceived as the weakness of the anarchists’ philosophy. In the Talbots’ version, Gilman, who will eventually write Herland, instead recalls a delightful evening spent with Michel around that time discussing their shared obsession with utopian novels. (‘She was full of fantastical ideas.’) Monique and Gilman reflect on fiction’s potential as ‘food for the mind’, and sci-fi becomes a creative lens through which The Red Virgin can view the life of a nineteenth-century political radical.

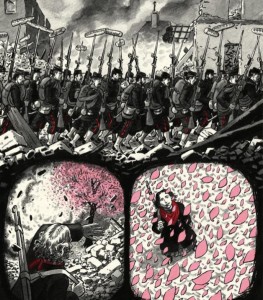

In an otherwise almost exclusively black-and-white visual narrative, splashes of red link flowers, flags, banners, scarves, pens, books, and a giant octopus. There are a few other significant shifts in colour. The sky turns rosy at the pivotal moment on March 18th when the French government sent the regular army soldiers to steal Montmartre’s canon from the city militia, the National Guard. Later, in two wordless images, a missile hits a cherry tree: chassepot on her shoulder, Michel looks up through an explosion of pink blossom. Here the Talbots exquisitely evoke the hope and destruction of the ‘temps des cerises’, and also Michel’s ‘curious aesthetic’ – a slightly disturbing capacity to see beauty in bombs, to be enchanted by revolutionary destruction.

The graphic format lends itself particularly well to interacting narratives: hard white frames seperate the Gilman/Monique conversation from the soft blurred edges of the story it narrates. But when it comes to the massacre in Paris that followed the invasion of the Versailles army – the paving stones ran with blood as the city burned – all borders vanish. The horror can’t be contained. A fog of ash descends like snow, and the flies gather over thousands of lime-sprinkled stinking corpses.

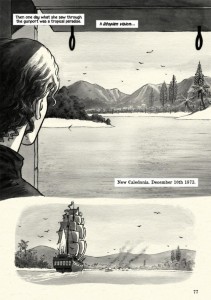

The Commune only lasted 72 days, and rightly takes up about half of this book. Naturally I’d hoped the rest would take in a little more of Michel’s life in London, including perhaps her school in Fitzrovia, and her houseful of cats, but tight selection is precisely the art of a biography like this. The sequence depicting Michel’s deportation to New Caledonia and her support of the indigenous Melanesians’ revolution more than compensates. It cleverly reveals the double-standards and blindspots not only of her fellow Communards-in-exile but also Charlotte Perkins Gilman, showing just how unusual Louise Michel was in her empathy for all the oppressed of this earth, regardless of race, class or gender. She was equally zealous in her attention to needy animals.

Published on the 400th anniversary of More’ Utopia, this book both simplifies and complicates the story of the Commune and its thinkers and activists; it does so beautifully, by putting the imagination centre stage, and looking at the past with an eye always on the future.

The Red Virgin and the Vision of Utopia by Mary M Talbot and Bryan Talbot was published by Jonathan Cape last month. This review was first published on my own website: www.lydiasyson.com. More Paris Commune reading recommendations here.

2 comments:

That book looks amazing!

Fascinating! Must read the book

Post a Comment