A few years ago we used often to stay with friends in Montpellier in the south of France (it's a fabulous city) and each time we went we would make a trip to the possibly even more fabulous walled mediaeval town of Aigues Mortes.

It's the perfect walled city, with a history that begins in the neolithic and runs on through the Romans to Charlemagne, who built the first tower - and on though the reigns of St Louis and his son Philip the Bold. Once an important port, it silted up during the 18th century, so no significant modern expansion ever occurred, and the town still fits neatly within its massive rectangular walls like a nut inside its shell.

But this post isn't going to be about the town, rather something I found in the town, while browsing the fascinating little shops lining the narrow streets which lead into the central Place de St Louis.

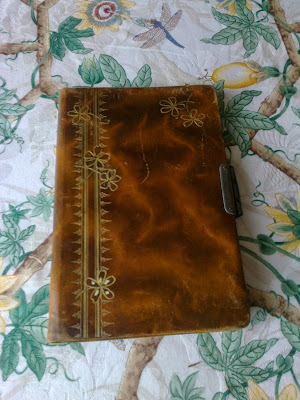

In a small antique shop, I picked up a little leather-bound book. It looked like a diary, with a lock and a key.

I opened it to find beautiful end-papers...

... and then, this hand-painted illustration: a sunburst inscribed 'FRANCE CATALOGNE', rising behind a lozenge displaying the Catalan colours, framed in branches of laurel. Below that, a ribbon of the French colours, inscribed with the words ' HONNEUR A LA 7e DU 53e '

I turned the next page. Here was a beautiful trail of ivy leaves and, written in French, these words (my translation), followed by a verse by the Catalan poet Apel·les Mestres i Oñós (1854-1936):

This album in which we have written our most noble thoughts, this flag upon whose silk our nimble fingers have embroidered 'La croix de guerre', imperishable glorification of your courage, we offer to you, Catalans from the other side of the Pyrennees, our heart's brothers. champions of all liberty, immortal heroes of the great war, whom we will forever recognise as having fulfilled the cry of your poet:

No

passareu!, i si passeu,

quan tots haurem deixat de viure,

sabreu de sobres a quin preu

s’abat un poble digne i lliure.

quan tots haurem deixat de viure,

sabreu de sobres a quin preu

s’abat un poble digne i lliure.

Mes no

serà! Per més que feu,

No, no passareu!

No, no passareu!

You shall not pass! and if you do,

When we all cease to be

Then you shall know the price

Of beating a free and noble people.

But it shall not be! Despite all your efforts,

No, you shall not pass!

Barcelona, 28 May, 1918

(I'm indebted to a young Catalan friend of my daughter's for the translation of the verse.) Next came yet another elaborately decorated page, a dedication 'To Captain Barthés, Knight of the Legion of Honour, Commander of the 7th Company of the 53rd Infantry Regiment', above a drawing of the statue of the Winged Victory of Samothrace, which is in the Louvre.

And after that, the book is full of signatures and dedications in both French and Catalan, praising brave Catalan men who sacrificed their lives in the defence of France and liberty.

What was all this about? - I wondered. Well, Spain remained neutral during the First World War. However, many Catalans felt alienated from the government in Madrid, which they felt did not fairly represent or defend their interests. Catalan industry had struggled after Spain lost Cuba during the Spanish-American War in 1898. Exports plummeted; they were unable to compete with British rivals on the overseas markets, while the domestic Spanish market was limited by its poverty.

"The First World War may not have involved Spain, but it resonated for many Catalanistas. One of the subtexts of that War was the right of small nations to self-determination in the face of predatory imperial powers. In addition, the Irish revolt of 1916 not to mention the growing voice of Basque separatism, had an emotional impact on more vocal Catalanists...". (From 'Spain Then And Now' http://www.spainthenandnow.com/spanish-history/catalonia-1900-1923/default_258.aspx)

The result was that significant numbers of young Catalan men - estimated at between 12,000 - 15,000 - volunteered to join the French army. The majority were killed; it is thought only 2000 or so ever returned home.

Frustratingly, that's as much as I can find out. I'm sure if I read Spanish or Catalan, I could discover more. I'd love to know who Captain Barthés was, and what he did to be awarded the Legion d'Honneur. I'd love to hear the story of the young men who went north to fight for their ideals. If anyone reading this post can point me in the right direction, I'll be very grateful. In the meantime, all I can do is turn the pages of this beautiful tribute to the bravery of the young men who went away to fight and who probably never came back. I read the names of those who signed it. Lolita Perez y Meila, Maria Carjinell, Rosita Sala, Angela Coch, Paquita Pascual, Conchita Pascual...

And Dolores Soler, Presentacion Roldan, Conchita Panas, and Carmen Boliva, whose brief Catalan messages are to me only partly decipherable, save for one. 'Oh guerra malahida!' - 'Oh, cursed war!'

5 comments:

Wow! What a find! Coincidentally my post tomorrow is about favourite finds, but on a much less spectacular note - that's a thing of beauty indeed you found! (Great minds thinking alike, right?)

Wow! Exactly my reaction too, Joan. I visit Aigues Mortes regularly (I live less than two hours away) and have never stepped foot inside any antique shop with such offerings. I must look more carefully next time. What a find. I would be fascinated to learn the history too. Thank you

That's an amazing find, and how interesting! I was in Catalonia, French Catalonia that is, for a wedding, and became aware of that part of history. Thanks for adding to what I knew!

The Musee de la Legion d'honneur might be able to help you track down Capt. Barthes, and find ou why he ws given the award.

http://www.legiondhonneur.fr/en/page/find-honorees/554

Amazing. Living history.

This words "No passareu", from the poem of Apel·les Mestres, were the origin of the spanish slogan "No pasarán" adopted by the Republican Army in the defense of Madrid (against the Franco's rebel army) at the war in Spain (1936-39).

The poem was written in protest by the invasion of Belgium during the First World War. Because of this poem, France also distinguished Apel·les Mestres Knight of the Legion of Honour and also awarded him with the Academic Palms of France.

I don't know if "after that", this words becamed also the devise/motto of the "53 regiment", wich is a militar unity of the french army but from Northern Catalonia (since 1659 this part of Catalonia belongs to France).

The point is that all the signatures and dedications are writted in catalan, and so it means to be writted by spanish Catalans (at that time, the possibilities for a french Catalan of being able to writte correctly in catalan were almost null -in France the school and the only official language was the french, the idiom of the culture there-).

This fact is even more evident with the presence of a dedication in spanish, in the second photo: in spanish Catalonia there was not either scholarization in catalan until 1931 -with the democratic Republic-, even though there were newspapers, magazines, books or theater in catalan, and a lot of people were able to write it).

The "problem" is to link Capitaine Barthés (that was a man from the 53 Regiment, the french catalans unity) with the spanish catalans that had writted in that book, because the spanish catalan soldiers were engaged in the Foreign Legion, as they weren't french citizens.

But this can reveal that the relation between catalans (frenchs and spanishs ones) existed despite the separation in different states or in different parts of the army

"B. Rius Teixidor" seems to be Benvingut Rius Teixidor (1872 - 1949), a catalan arquitecht: what fits in the type of draw.

Please, don't let this document get lost! (Take into consideration to donate it, for example to the History Museum of Catalonia)

Post a Comment