I am delighted to welcome Emma Barnes, aka E.J. Barnes, the author of MR KEYNES REVOLUTION, to the History Girls blog today.

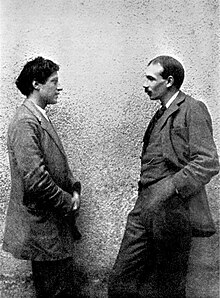

Emma's newly published historical novel, which I very much enjoyed, is about the intriguing relationship between the economist John Maynard Keynes and Lydia Lopokova, the talented ballerina who had danced with Diaghilev. Keynes met Lydia in London, in 1921, while she was appearing as the Lilac Fairy in Sleeping Beauty.

As someone who is lightly fascinated by the Bloomsbury Group, I admit I experienced a slightly wicked pleasure in observing, through Emma's writing, how much this romance ruffled the feathers of Keynes family of friends. The two sisters at the heart of the Bloomsbury circle - the artist Vanessa Bell and the author Virginia Woolf - were irritated by Lydia's forthright style and direct manners, and considered her a vulgar foreigner who danced professionally for money.

Keynes' love affairs had previously been with young men, so most of the Bloomsbury set, both male and female, hoped his new passion would fade, leaving their elite aesthetic circle unchanged, as well as still supported by Keynes quiet financial generosity. In the novel, Lydia, who knows about hardship and poverty, wisely comments: "You mean your friends, the ones they call Bloomsbury, if they don't care for money, that's because they have plenty of it."

A particular strength of this novel is that, alongside the warm but unusual romance, a more political drama is unfolding. Emma Barnes shows Keynes - writer, academic, art lover and investor - struggling to make goverment ministers and bankers appreciate the consequences of their financial decisions. Although not a knight on a white charger, Keynes' continuing battle against poor postwar economic choices does read quite heroically, and feels more than relevant to the situation in which we now find ourselves.

Emma, thank you for agreeing to be interviewed about your first historical novel: I'd like to ask you a few questions.

Q. Why did you choose Keynes? What is it about his character that interested you and inspired you?

A. I'd known about Keynes' work since studying economics, first at school, and then at Cambridge University. where he still loomed very large in the landscape. But I didn't know anything about his life until I read a book called Mrs Woolf and the Servants, which rather circuitously led me to Keynes via the Bloomsbury Group. I was amazed to learn of Keynes' many gay love affairs, and sudden passion for a ballerina. I was also fascinated by his involvement in so many worlds: high finance, government, journalism, academia, the arts and Bohemia.

Above all, I felt his struggles spoke to ours. He lived in a time in which complacency about politics and economics was overtaken by crisis and extremism. Civilisation itself was under threat. His mission was a heroic one: to find a humane capitalism that could serve as an underpinning for a democratic, civilised, peaceful society. Maybe there are some pointers for us now.

Q. Why did you choose the 1918 Paris Peace conference as the opening point of your novel?

A: Originally I wrote a quieter start, but I loved the drama of the Paris Peace Conference: Maynard Keynes, who has been so successfully negotiating the corridors of power, suddenly has had enough. He see the politicians are failing everyone and walks out. It sets up the themes of the book: a complacent and callous establishment, and the dilemma of someone who both belongs and does not belong, but can never just walk away.

Q. Two of the central locations of the novel - Kings College, Cambridge and Charleston, the Bloomsbury's Sussex retreat - are beautifully described. Were you able to visit these settings specifically for your novel Mr Keynes Revolution?

A. Yes, I've stayed at Kings, and I was lucky enough to see the paintings that Duncan Grant and Vaness Bell produced for Maynard Keynes rooms. At Charleston, I fondly remember the scones in the heavenly gardens. Charleston is a work of art in itself: you can see why it was sucha haven for the metropolitan and vastly overworked Maynard Keynes.

Q. Much has been written in admiration of the Bloomsbury movement but I felt that your novel offers a gently humorous sideways view of the group. Vanessa, on occasions, is shown as intellectually snobbish, waspish and possessive, despite Bloomsbury's belief in liberty and sexual freedom. She is a complete contrast to Lydia, the practical "little pony" of a ballerina, comfortable in her all-too-visible skin, and at ease with both the servants and the need to make money. How did you develop your ideas about Lydia?

A. Bloomsbury were never at their best in their dealings with Lydia. In fairness, Maynard did rather hurl her into the group with little regard for how they might respond. But their response was not generous. Bloomsbury did give Maynard a great deal though - not least, a lasting ideal of art and friendship that inspired him throughout his life.

Lydia herself is an astonishing character. She had an amazingly colourful life, from a childhood in Tsarist Russia to stardom on Broadway and with the Ballets Russes, to love affairs, to acting Shakespeare and Ibse, to a long and eccentric old age. More than this, her spirit and originality were noted by everyone and emerge strongly in her letters.

For those who want to read about her life I would recommend Judith Mackrell's biography, Bloomsbury Ballerina, and the published letters, Lydia and Maynard. Writing the novel, it was a challenge not to portray Lydia in a way that felt over the top. In many ways, she was larger than life, although I think the extrovert persona also disguised a degree of personal tragedy, and so I was concerned that the fictional version might appear to be a caricature. I've tried to convey her vulnerability and her courage.

Q. In your novel, Keynes romance and some of its complications are very much rounded out by the chapters written from the servants point of view. Where did this strand come from?

A. I've long been interested in servants - my own great-grandmother was a maid. Domestic service was the biggest employer in the early twentieth century but it's a very hidden world. I've always been interested in the memoirs of servants, and also enjoyed Lucy Lethbridge's Servants. The most direct source was Alison Light's Mrs Woolf and the Servants which explores the lives of several Bloomsbury servants in detail. The character of Lottie is particularly influenced by that book. Gates alone is entirely my invention although his storyline is still inspired by historical events.

The relationship of servants and their employers is fascinating: intimate, sometimes affectionate but also often exploitative and filled with unexpressed resentments. For employers like Bloomsbury - trying to overturn social conventions, attempting to be progressive, yet undeniably part of a privileged elite - the relationship creates particular tensions.

Q, You mentioned writing this as a screenplay. Did that format help you when it came to writing and pacing this as a historical novel?

A. Yes and no. It meant I was familiar with the material but a novel is a very different form and written straight from a screen play would be "choppy." There's more space for introsepction, and I also had to think of historical accuracy all over again - with a screenplay, it's impossible to be completely accurate within the constraints of a two-hour script. With a novel, there's more flexibility so you need to think exactly what you are trying to achieve. A novel is usually more intimate which actually means it has covered a shorter span of time, but in more detail, than a screenplay.

Q. Which was the hardest scene to write? And your favourite scene to write?

A. The opening chapter, at the Paris Peace Conference, was a hard one in terms of it being a big historical event with a lot of detail to get right. Some of the economic discussions are also tricky because you are trying to convey quite difficult subject matter, without overwhelming the reader or losing dramatic tension. At the end of the day, economics is at the heart of what Keynes was about but economic theory rarely crops up in novels so that was a challenge!

My favourite scene is Lydia and Maynard on the Sussex Downs after the ill-fated Charleston party.(Seconded here, by the way!)

Q Emma, I became very involved with your main characters and their worlds as I read on through Mr Keynes Revolution. Do you have any future plans for these characters?

A. Yes. This novel finishes in 1925. I am working on a sequel which contains many momentous challenges for Maynard and Lydia, including a trip to Bolshevik Russia and the Great Depression. I'm enjoying it!

Emma - E.J. Barnes! - thank you for answering all my questions here on History Girls. Good wishes on this novel - and on the next.

E.J.Barnes

Interview by Penny Dolan

MR KEYNES REVOLUTION by E.J.BARNES. Longlisted for The Peggy Chapman-Andrews First Novel Award . Greyfire Publishing ISBN 9780993515835 . www.EJBarnesAuthor.com