For my own novels, The Meonbridge Chronicles, recorded history is not, for the most part, a fundamental aspect of the stories but rather a background against which they are set. Neither my setting nor my characters are real, so I am at liberty to make up everything about them. But that is not to say I don’t strive for authenticity in the way I write about the people and the time – of course I do. Research into the medieval way of life is still very important for me. And I have dozens of books to help me, acquired over the years I have been writing historical fiction. But I do use online resources too, with a suitable degree of circumspection about their likely veracity.

But one online source I do return to time and time again, not because it tells me much about my characters’ “way of life”, but because it gives access to a wealth of fascinating documents that offer all sorts of snippets of information that can feed your imagination as a novelist, is British History Online (BHO).

I first posted a version of this on The History Girls blog back in July 2017, but I thought the idea was worth reprising, for those readers who don’t know about BHO, but also because what I learned about the history of the nearby village of Meonstoke I continue to find deeply fascinating and hope you might too. Alternatively, you might want to explore what BHO has to tell you about the history of your own village, county, town or city.

Browsing the British History Online website can while away many a happy hour in a fascinating, sometimes surprising, experience. If you don’t know of it, BHO is a digital library of key printed primary and secondary sources for the history of Britain and Ireland, with a primary focus on the period between 1300 and 1800.

The website offers an astonishing number of documents. To pick at random from the catalogue index, just to show the sort of documents available…

EXAMPLE 1: Feet of Fines, Sussex

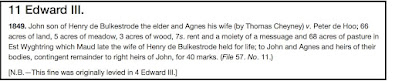

Feet of fines are court copies of agreements following disputes over property. In reality, the disputes were mostly fictitious and were simply a way of having the transfer of ownership of land recorded officially by the king’s court. The records in this series relate to the county of Sussex for the period 1190-1509. I’d need to brush up on my Latin to make sense of the Edward I volumes, although those for Edward III are in English…

|

| ‘Sussex Fines: 21-25 Edward I (nos. 1072-1118)’, in An Abstract of Feet of Fines For the County of Sussex: Vol. 2, 1249-1307, ed. L F Salzmann (Lewes, 1908), pp. 159-169. See British History Online [accessed 7th May 2023]. |

|

| ‘Sussex Fines: 11-15 Edward III’, in An Abstract of Feet of Fines For the County of Sussex: Vol. 3, 1308-1509, ed. L F Salzmann (Lewes, 1916), pp. 88-102. See British History Online [accessed 7th May 2023]. |

EXAMPLE 2: Calendar of Close Rolls - Edward III (14 volumes)

The Close Rolls record “letters close”, that is, letters sealed and folded because they were of a personal nature, issued by the Chancery in the name of a particular king or queen. They usually contained orders or instructions. These “calendars” provide summaries full enough, for most purposes, to replace the original documents. However, these particular documents are designated on the BHO as “premium content” and require a subscription to access that I don’t have, but would surely be of great interest to anyone researching into the lives of a particular monarch.

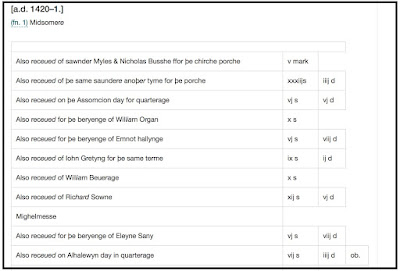

EXAMPLE 3: The Medieval Records of A London City Church St Mary At Hill, 1420-155

Edited by Henry Littlehales, these records were first published by the Early English Text Society in 1905. They are churchwardens’ accounts for the St Mary At Hill parish. The records are at their fullest for the period from 1480 onwards. The volume also has an extensive introduction, detailing the history and liturgical practice of the church, and the impact of the Reformation. Looking at this page, you’d clearly need to understand the notation used for the accounts, but it’s potentially fascinating stuff!

|

| The Medieval Records of A London City Church St Mary At Hill, 1420-1559, ed. Henry Littlehales (London, 1905), See British History Online [accessed 7th May 2023]. |

Anyway, the part of BHO that I generally head for is the Victoria County History for Hampshire. A History of the County of Hampshire: Volume 3: Edited by William Page. This covers eastern Hampshire, including Portsmouth, Southampton, Petersfield and Havant, and was originally published by Victoria County History, London, 1908. See British History Online [accessed 7th May 2023].

The Victoria County History was begun in 1899 and dedicated to Queen Victoria. Organised by county, it provides a vast and detailed record of England’s places and people over many centuries. It has been described as the greatest publishing project in English local history, and it certainly does provide a wealth of information.

The entries I return to in the Victoria County History are those for the Hundred of Meonstoke in the Meon Valley, and the Parishes of Meonstoke.

If you'd like to look them up, see: 'The hundred of Meonstoke: Introduction', in A History of the County of Hampshire: Volume 3, pp. 245-246. British History Online and ‘Parishes: Meonstoke’, in A History of the County of Hampshire: Volume 3, pp. 254-257. British History Online.

The information IS old, of course, written in the nineteenth to early twentieth century. It isn’t brought up to date, as far as I know. But, if the information you are looking for is about the fourteenth century or earlier, as is true for me, that really doesn’t matter.

A “hundred” was a division of the shire. Hundred boundaries were independent of both parish and county boundaries, though they were often aligned, so a hundred could be split between counties, or a parish could be split between hundreds. The Meonstoke Hundred contained a number of parishes and some tithings that were part of other parishes.

The setting for my Meonbridge Chronicles is not actually Meonstoke, but I have a sense that “Meonbridge” lies broadly in the area occupied by Meonstoke and its neighbouring villages, so I was interested to read what the History could tell me about these villages and their development over time. I don’t necessarily use much if any of what I’ve learned in my novels, but research is a thrill in its own right, isn’t it? Just reading this kind of stuff can be a delight.

Various things drew my interest…

For example, the way the structure of the hundred changed over time. At Domesday, Meonstoke consisted of ten parishes, and a tithing from another parish/hundred but, by 1316, it was down to four parishes – Meonstoke, Soberton, Warnford, and Corhampton – plus three tithings from three other and different hundreds (‘The hundred of Meonstoke: Introduction’, Paragraph p3).

Then there is the way that the names of places changed over time, or perhaps were simply recorded with different spellings. So, for example, Meonstoke was Menestoche in the 11th century, Mienestoch or Mionstoke in the 12th; Manestoke or Menestoke in the 13th; Munestoke, Munestokes, Maonestoke or Moenestoke in the 14th (‘Parishes: Meonstoke’, Paragraph p1).

But perhaps what really drew my attention about Meonstoke were the names of some of the owners of its manors – including both illustrious and notorious individuals – which give Meonstoke a seemingly glittering past that sits somewhat strangely with the rather peaceful, out-of-the-way, “backwater” it might appear to be…

The “glitter” derives perhaps from the fact that Meonstoke was always part of the king’s demesne. It formed part of the lands of King Edward the Confessor, and, at the time of the Domesday Survey, being part of the crown’s demesne, it was not assessed. But, in the reign of Henry III, it was divided into three portions and, from then until the 14th century, there were three manors of Meonstoke – Meonstoke Tour, Meonstoke Ferrand and Meonstoke Waleraund (later Meonstoke Perrers), each with a distinct history (‘Parishes: Meonstoke’, Paragraph p4).

|

| Effigy of William Edington in Winchester Cathedral. By Ealdgyth [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons |

Meonstoke Tour was land granted by Henry III to one Geoffrey Peverel but, in 1240, it was back again in the hands of the king, who then granted it to his serjeant Henry de la Tour. The manor remained in the hands of the de la Tour family from then until 1353, when it was sold to no less a personage than William de Edendon (or Edington or Edyngton – medieval spelling was not consistent!), the Bishop of Winchester. In 1366, the then king, Edward III, wanting to reward William for his long service, tried to appoint him Archbishop of Canterbury, but William was already in failing health and he declined the honour. He died in the October in nearby Bishop’s Waltham, and is buried in Winchester Cathedral. The new bishop was William of Wykeham (a Meon Valley man, born in Wickham, and one of the area’s most illustrious sons), who bought the manor from de Edendon’s executors and merged it and the other two manors back into a single “Meonstoke” manor (‘Parishes: Meonstoke’, Paragraph p7).

|

| Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain and Bishop of Winchester, William of Wykeham (1320-1404). Engraving by Charles Grignion (1754-1804). Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. |

Meonstoke Ferrand’s land was granted by Henry III to his Gascon crossbowman Ferrand in about 1233. A Ferrand then held the land until 1305, when it was sold to John de Drokensford, who was bishop of Bath and Wells. For the next fifty years, Drokensfords held the manor, until it seems to have been sold as part of a larger transfer of messuages (dwellings with their adjacent buildings and lands), other land and mills by one Maurice le Bruyn. The buyer we have met already – William de Edendon (Edyington, Edington…), the bishop of Winchester. After his death, Meonstoke Ferrand was also bought by his successor, William of Wykeham, who merged it with the other manors (‘Parishes: Meonstoke’, Paragraph p6).

And so we come to Meonstoke Waleraund, or Meonstoke Perrers, as it later became. And this is the story in the BHO that particularly intrigued me because of its second name… It is first mentioned as a separate manor in 1224, and was held briefly by a de Percy but, in 1229, Henry III granted it to one Fulk de Montgomery. But, two years later, Fulk sold it to Sir John Maunsell, who obtained a grant of a weekly Monday market in Meonstoke and a yearly fair on the “vigil, feast, and morrow” of St. Margaret, and, two years later, also a grant of free warren (permission from the king to kill certain game within a stipulated area) in all his lands in Hampshire.

Sir John was a favourite of the young King Henry III and is thought to have obtained vast numbers of benefices all over the country, perhaps more than any other clergyman, including the provost of Beverley, in 1247, the livings of Howden, Bawburgh and Haughley, the prebendaries of South Malling, Tottenhall, Chinchester [sic – I assume Chichester], the dean of Wimborne, the rector of Wigan, and the chancellorship of St. Paul’s, London, as well as papal chaplain and chaplain of the King. He also served as the Lord Chancellor of England. A powerful man indeed!

|

| Statue of Simon de Montfort on the Haymarket Memorial Clock Tower in Leicester. By NotFromUtrecht [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons |

But when Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, grew in power, King Henry was forced, apparently against his will, to deprive Sir John of his possessions, granting them to Simon in 1263. Although, another story says that it was after the battle of Lewes in May 1264, when de Montfort defeated Henry and took power, that he deprived Sir John of all his lands. Whether the “deprival” included Meonstoke I am not clear, but perhaps it was at one time owned by the notorious de Montfort.

However, after the battle of Evesham in 1265, when de Montfort himself was defeated, Sir John was already dead, and Meonstoke passed to another de Percy. But, only three years later, he sold it to Robert Waleraund, and the manor remained in the hands of Waleraunds or their descendants until perhaps 1370 or thereabouts, when the manor escheated (was returned) to the king, Edward III. And he then granted it to trustees for the use of his mistress, the famous, or infamous, Alice Perrers, at which point the manor came to be called Meonstoke Perrers.

|

| Detail of an imagining of Alice Perrers and Edward III by Ford Madox Brown (1868), showing Chaucer reading to the king’s court. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

Whether or not Alice ever visited her new manor of Meonstoke Perrers I have no idea, as I believe she had many manors to choose from to rest her head, but it is nice to imagine that she might have spent a night or two at least in the lazy backwaters of the Meon Valley…

However, in 1376, the “Good” Parliament banished Alice and deprived her of her possessions, although in the following year, the “Bad” Parliament reversed the decree and she regained them. But then, in the first Parliament of Richard II, the sentence against her was reconfirmed, and Meonstoke escheated once more to the crown. The manor was put into the hands of stewards until 1379, when the sentence against Alice was yet again revoked, and the manor was granted to her husband, William de Windsor. But, only months later, he sold it to our friend William of Wykeham, bishop of Winchester (and also chancellor to both Edward III and Richard II), who merged it with the two other Meonstoke manors and eventually granted it to his foundation, Winchester College (‘Parishes: Meonstoke’, Paragraph p5).

This must have been the lot of hundreds of manors throughout the country – this toing and froing between owners as their status soared and dived at the whim of those in power. One wonders what the tenants thought of it all? Probably nothing. It was no concern of theirs. They undoubtedly just kept their heads down and got on with their work. I suppose, in many cases, tenants scarcely knew their “lord”, if he or she was of the absentee type, as I am sure all of those I have mentioned here must have been. As far as tenants were concerned, their masters were the reeve and steward or bailiff, and their own lives were lived with no connection to the, possibly illustrious, person who actually benefited from the results of their labours.

Most of this information is pretty “random” and, as it happens, has proved of no use to me in my novels. But that doesn’t stop me finding it hugely fascinating. I have explored the histories of other villages around this part of Hampshire, with some equally intriguing, if not necessarily such “glittering”, results.

If you are interested in the history of old England, you might too find something to intrigue you in British History Online.