Today’s post will be the first in a series linked to my new

novel, The Night in Question, which will be published in October. The book

deals tangentially with the Whitechapel Murders of 1888 and researching it was

an interesting mix of surprise and familiarity. My great-grandmother, whom I

knew briefly, would have been 12 years old at the time of the murders. I wonder

whether they talked about Jack the Ripper in rural Wiltshire?

Not being a Londoner one of my research surprises was the

discovery that in 1888 Whitechapel

already had two Underground stations

- Aldgate East and St Mary’s, with another (Whitechapel station) under

construction. In fact Underground travel was already old hat by then and much improved from this 1860s prototype.

St Mary’s station no longer exists. It was closed to passengers in the 1930s

and only reopened briefly at the start of WW2, to be used as an air raid

shelter. The station building took a direct hit in 1940 and was demolished but

the platform apparently still exists, walled off from view as the Upminster

trains rattle through. A ghostly relic of Victorian London.

So in 1888 how did most people get around? In an

impoverished area like Whitechapel shanks’ pony was the norm. People walked

miles every day even if they’d had to pawn their boots and go barefoot. Being a

pedestrian was anyway hardly a pleasure. Pavements were narrow, streets were

crowded with wheeled vehicles and the Highway Code was still a distant prospect. The great stone/asphalt argument swung back and

forth too. Carriage wheels on granite created a lot of noise. Asphalt was much

quieter but was dangerous for horses. All it took was a light coating of rain and asphalt became a skating rink beneath horseshoes. And then there was the smell. In the 1880s London had

around a thousand tons a year of horse dung to deal with.

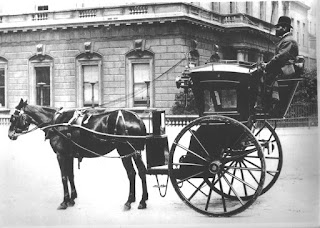

The hansom cab so beloved of period movie makers would have been an

affordable option for my protagonist, Dot Allbones, but hardly a luxurious one.

It was a jolting kidney-shaker, carrying two passengers, three at a squeeze. With just

two wheels it didn’t hold the road well and you were at the mercy of a driver

who sat in a high, rear seat and who might well have had a drink or two. The four-wheeled growler, or clarence as it

was sometimes called, was more commodious and more stable. It had room for four

passengers and luggage too. You would have easily found a growler for hire outside

Liverpool Street station for instance.

The other options were horse buses and horse trams. In the

early 19th century the buses had reigned supreme although the top

deck, reached by ladder, was used by only the most determined of females. By

the 1880s, buses had improved greatly, with proper stairs to the upper deck and seats

that faced forward instead of rudimentary bench seating. Nevertheless buses were losing

trade to the trams. It was matter of Newtonian physics. A tram glides on its track more easily than a horse bus

trundles on its wheels. Less effort was required of the horses which in turn

meant that a tram could carry more passengers and fares became more competitive.

At just a penny a mile market forces were at

work. The horse tram became the commuter's preferred mode of transport and a practical choice

for Dot Allbones on the morning she needed to travel from Hackney to the Golden Lane

mortuary on a sad and sobering errand.

2 comments:

Thank you for an interesting post!

Just come late to this, Laurie...very interesting and can't wait to read the book!

Post a Comment