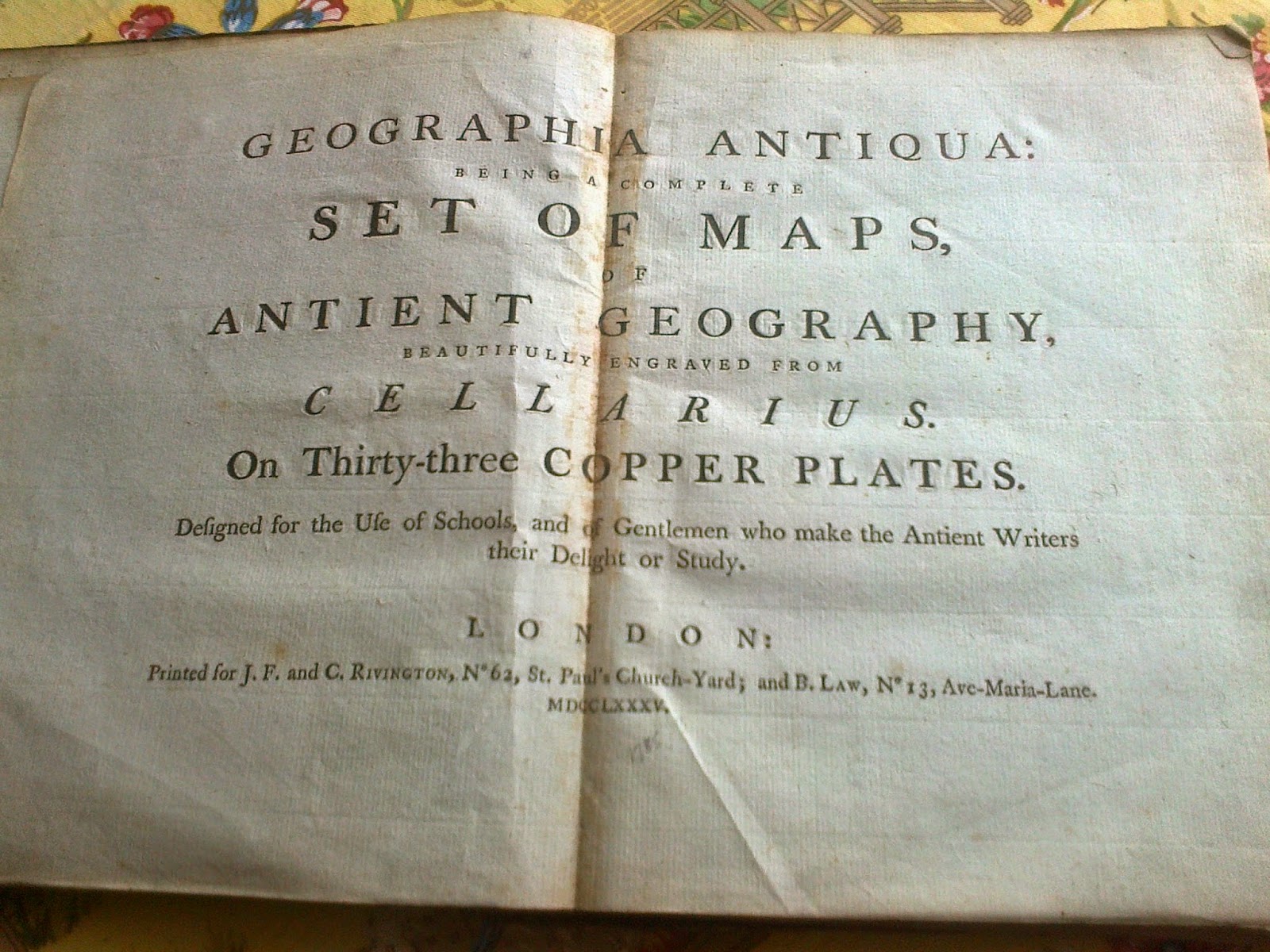

I suppose my grandfather must have been given it by someone else - in fact, it must have been handed down for generations. It's an atlas of the classical world, dated 1785: 'Designed for the Ufe of Schools, and of Gentlemen who make the Antient Writers their Delight or Study.'

The maps cover all areas which such Gentlemen might wish to consult while following the journeys of Herodotus, or perhaps the campaigns of Alexander, or the Gallic Wars.

Of course they are deliberately limited to the parts of the world known to ancient geographers: but they aren't themselves ancient. They're drawn to an eighteenth century knowledge of the shapes of coasts and continents.

Like any historical atlas of today, they fit the old stories into what was then a modern frame. Here for example is Mesopotamia, with its squiggly rivers, the Tigris and the Euphrates.

But I wanted to go looking for griffons, and in a way I found them. In Book Two of Paradise Lost, Milton describes how Satan launches himself out on his 'Sail-broad Vannes' into the abyss of Chaos:

As when a Gryfon through the Wilderness

With winged course ore Hill or moarie Dale,

Pursues the Arimaspian, who by stelth

Had from his wakeful custody purloin’d

The guarded Gold...

With winged course ore Hill or moarie Dale,

Pursues the Arimaspian, who by stelth

Had from his wakeful custody purloin’d

The guarded Gold...

So - who were the Arimaspians? It turns out they come into the first century 'History of Alexander the Great' by Quintus Curtius Rufus: they were also known as the the Euergetae, the Benefactors, whose kindness had once saved the army of Cyrus the Great of Persia. Alexander, a fan of Cyrus, respected these people for assisting his hero, and also for their laws and customs which the 2nd century historian Arrian reports 'had as good a claim to fairness as the best in Greece.' Nothing, sadly, about stealing gold from griffons. That's left to Herodotus, in Book 4 of his History: 'Aristeas ... son of Caystrobius, a native of Proconnesus, says in the course of his poem that wrapt in Bacchic fury he went as far as the Issedones. Above them dwelt the Arimaspi, men with one eye; still further, the gold-guarding griffins; and beyond these, the Hyperboreans, who extended to the sea.'

Wow. They have only one eye, and still succeed in robbing griffons? But here they are, the Ariaspae, Euergetae, halfway down the map on the left-hand side.

I went hunting for more. Here, at the top of the map of Scythia and Serica (peppered with cities called Alexandria), on the very verge of Terra Incognita, are the Anthropophagi, Eaters of Men, while below them, fittingly a little less distant, a little less uncivilised, we encounter the Hippophagi, eaters of horseflesh.

Pliny the Elder describes them: "The Anthropophagi, whom we have previously mentioned as dwelling ten days' journey beyond the Borysthenes, according to the account of Isigonus of Nicæa, were in the habit of drinking out of human skulls, and placing the scalps, with the hair attached, upon their breasts, like so many napkins."

It doesn't sound impossible, but I feel that Ammianus Marcellinus was embroidering when he adds: "And these men are so avoided on account of their horrid food, that all the tribes which were their neighbours have removed to a distance from them. And in this way the whole of that region to the north-east, till you come to the Chinese, is uninhabited." Although that's the China Sea, there, at the eastern edge of the map...

I've always had a soft spot for the Anthropophagi since first meeting them in The Sword in the Stone: Robin Hood explains,

‘Now, men... You know about these Anthropophagi, and how we have

lost Matthew, Peter, Walter, Colin and many others. God rest their souls. Tonight the Anthropophagi are holding one of

their feasts of sacrifice and it behoves us to slay them at it.

‘You know how many varieties they have. The Scythians, who wrap themselves in their

ears, can hear a twig break half a mile away. The Pitanese, who live by smell,

can detect a man upwind for three miles.

The Nisites, with three or four

eyes, can distinguish the faintest movement anywhere. All these men, or beast

if you prefer to call them so, are ... armed with poison arrows. Our chances are small.’

Sir John Mandeville knew of creatures like these, living in the Island of Dodyn - not to be found anywhere in my maps, alas - and had more to say on griffons, this time from Bactria, north of the Arimaspians:

'In that land are trees that bear wool, as it were sheep, of which they make cloth. In this land are ypotains that dwell sometimes on land, sometimes on water, and are half a man and half a horse, and they eat naught but men, when they may get them. In this land are many gryffons, more than in other places, and some say they have the body before as of an Egle, and behind as a Lyon, and it is trouth, for they be made so, but the Griffen hath a body greater than viii Lyons and ... worthier than a hundred Egles. For certainly he will bear to his nest flying, a horse and a man upon his back... for he hath long nayles on his fete, as great as it were hornes of Oxen, and of those they make cups there to drink of, and of his rybes they make bowes to shoot with.'

Ypotains equal hippos, I suppose - and the wool growing on trees, might that be cotton - or even silkworms? Then why not griffons?

What fun for the eighteenth century Gentleman to muse on all this as he sat in his study, drinking his port.

1 comment:

What a fabulous old book. I love the marbled cover!

Post a Comment