Most of us in this group, since it started in 2011, have been writers of historical fiction. We’ve had “straight” historians, like John Guy, as guests and some of our number, like Clare Mulley have written non-fiction, Some people do both – and it can be quite confusing.

Take Alison Weir, for example. She, who has also been a guest on The History Girls blog, is a prolific writer on historical subjects such as the Wars of the Roses, Eleanor of Aquitaine, Henry Vlll and the Boleyn sisters. But she also writes novels about some of the same characters, notably her Six Tudor Queens sequence about Henry’s notorious marriages.

So how do they differ, since they inevitably share the same events and characters? I’ve had an opportunity to compare two books that cover some of the same period to see how a novelist chooses to write about the same plots that appear in a historian’s account of the identical events. The novelist is Alison Weir herself, in her new novel, published last May by Headline, Elizabeth of York: The Last White Rose. The non-fiction writer is Michèle Schindler, whose De la Pole Father and Son: the Duke, the Earl and the Struggle for Power, was published by Amberley last December.

So, two books about Plantagenet history and those famous roses, partly invented by Shakespeare, who was more a writer of fiction than he was a historian. Elizabeth of York was the daughter of Edward lV and his wife, Elizabeth Wydeville and was destined to become the wife of Henry Vll and Queen of England, uniting the houses of York and Lancaster. Weir’s novel about her is the first in a trilogy.

John de la Pole did not feature in a play by Shakespeare, although his father did. But it’s not that father and son combo Schindler writes about. That was William, the duke of Suffolk who stood proxy for Henry Vl at his wedding to Margaret of Anjou. No, it is John who inherited his murdered father’s title and married another Elizabeth, not Edward iV’s daughter but his sister. Are you muddled enough yet? John de la Pole, Duke of Suffolk, became Elizabeth of York’s uncle when he married her aunt.

The titles don’t really help: Weir’s doesn’t sound like a novel, although “The Last White Rose” does. Schindler’s might have been “The de la Pole dynasty,” since it begins with William, goes on to John and ends with John Junior, who was Richard lll’s named heir. Those de la Poles continued to be a thorn in the side of Henry Tudor for many years.

But if we look at 1470, we can see how different a novel is from a work of history. In this year, the Earl of Warwick (the “kingmaker”), conspired with George, Duke of Clarence to overthrow Edward lV, with a long-term view of putting George on the throne. In the short term, they made do with releasing the previous king, Henry Vl, from the Tower of London and parading him through the streets as the true king. Edward had fled to Burgundy with his younger brother Richard and Queen Elizabeth, heavily pregnant, had sought sanctuary with her mother and daughters in Westminster.

|

| Elizabeth Wydeville |

These events come 130 pages in to Schindler’s book and are described thus: “This must have been a tense time for John and Elizabeth. Since the party seeking exile in Burgundy included two of Elizabeth’s brothers, she must have been very worried about their fate…[T]hey would have learnt that Edward’s heavily pregnant wife, Elizabeth Woodville [sic], and their three daughters had fled to sanctuary in Westminster Abbey, that Elizabeth gave birth to a son shortly afterwards and that Henry Vl had been released from confinement in the Tower after five long years and reinstalled on the throne.”

This paragraph in the de la Pole book summarises twenty pages and more of the opening chapter of Weir’s novel, where the reader is thrust in medias res, as the princess Elizabeth and her sisters are bundled into a wherry and taken down the river, where they are warmly welcomed by the Abbot and given shelter. The long-awaited son and heir is born at the beginning of the second chapter.

But, since Elizabeth is only rising five, a lot of the history that has gone before can by explained to her by her grandmother and Weir can take the reader through recent events by this device, which she does very skilfully.

The elder Suffolk is barely mentioned in Weir’s novel, unsurprisingly since Schindler tells us how he kept himself out of politics and was not often at court. But there are occasional references in the novel to “Aunt Suffolk and her son Lincoln” and the younger John assumes an ever more important role. He was the Earl of Lincoln and would have inherited his father’s title if he had not come to a sticky end.

|

| Coat of Arms of John, 2nd Duke of Suffolk |

One thing that emerges both from the history book and the novel is the sheer number of children born to noble and royal women and the number of babies and children lost. John Senior and his wife Elizabeth, the Duke and Duchess of Suffolk, had thirteen children. Elizabeth of York’s parents had ten together and Elizabeth Wydevile had already had two sons by her first husband, Lord Grey.

What the novelist does is show you that a factual history can’t (and mustn’t): the emotions stirred by every birth and death. Even, or perhaps especially, the loss of an older child, is a cause for great grief. Here is Weir describing the death of Elizabeth’s closest sister, Mary, at fifteen:

“Elizabeth slept in her chair that night. She woke to find Mother rocking a corpse in her arms, keening softly, her cheeks streaked with tears. She burst out wailing.

Father came running, summoned by the doctor. He folded Elizabeth in his arms and held her tightly. ‘She is with God now. You must be glad for her.’ His voice broke, and he turned to the bed. ‘Our sweet angel is at peace, Beth.’ He embraced both the Queen and his lost child, then gave way to the most piteous weeping.”

There are many such losses described in the novel - siblings, infants, young adults - and it is touching to read in the Autor’s Note that Weir herself lost a son in 2020, which must have informed her accounts of royal grief.

Back to John Junior, Earl of Lincoln, who in 1480 married Margaret FitzAlan, a union arranged by the King, Edward lV. His wife was much younger than his eighteen years and they did not live together. Indeed his marriage doesn’t seem to have affected the Earl’s life at all and his star was rising at court. He played a part in the baptism ceremony for Bridget, the youngest child of the King and Queen.

|

| Edward lV |

Then came the shock of the unexpected death of the King in 1483. “The King’s eyes had closed. His face looked grey; his lips were blue. Gradually, his rasping breath slowed – and then there was silence.” Or, as Schindler succinctly puts it, “Edward’s death was sudden and shocking.” He was forty-one.

John Junior was chief mourner at the King’s funeral and soon came out in support of his uncle Richard of Gloucester as the new king. One of the new king’s closest friends, Francis Lovell, had been John’s foster brother and they were both part of the new court.

Elizabeth of York, however, was back in sanctuary at Westminster with her mother and siblings. In Weir’s novel, Richard is referred to as “the Usurper” and Elizabeth is stunned that her kindly “Uncle Gloucester” could have behaved so badly towards her family.

So we come to the most crucial events in Richard’s brief reign: the disappearance of “the Princes in the Tower” and Richard’s plan to marry his niece. The princes, Edward’s heir and his younger brother, the Duke of York, were kept in the Tower of London while, in justification of his seizing the throne, Richard claimed they were bastards, as King Edward had made an earlier, secret, marriage, before wedding Elizabeth Wydeville.

Weir’s novel is divided into sections: Princess, Bastard, Queen and Matriarch, the second section set during her uncle’s reign. Her mother is convinced that Richard has had her sons murdered and is prostrate with grief. Their old life has disappeared and everything is uncertain.

In Schindler’s book, John Junior “chose to remain loyal to his uncle,” as did his parents. In Weir’s novel, Elizabeth embraces all the different theories that have been put forward about the princes’ fate, beginning by sharing her mother’s belief. Then, when she has returned to court, Richard convinces her that the boys were put to death on the orders of Buckingham and he knew nothing about it.

Later, after Richard’s death, she suspects that her husband to be, Henry Tudor, or his mother might have been responsible for removing such strong claimants to the throne, smoothing the way for his accession. Towards the end of the novel, she hears evidence from relatives of Sir James Tyrell that he commissioned two named thugs to carry out Richard’s orders.

When Richard’s heir, the Prince of Wales, dies in 1484 he makes John Junior his heir. John is heir presumptive anyway, as the oldest son of Richard’s older sister Elizabeth, Duchess of Suffolk. (He is also the eldest living grandson of Richard Duke of York).

Soon after their son died, Anne Neville, the King’s wife, also succumbed, probably to tuberculosis. But before she died, rumours were flying around that Richard planned to marry his own niece, Elizabeth of York.

This is a major plotline in Weir’s novel. Quite apart from what seems to us like incest and the need for a Papal dispensation, how could Elizabeth even consider marrying the man who usurped her young brother’s throne and probably killed him and his younger brother? And yet the historical Elizabeth did write a letter to the Duke of Norfolk to advance her marriage to the king, vowing she was “his in heart and in thoughts, in [body] and in all.”

|

| Elizabeth of York |

Weir’s explanation is reasonably convincing: Richard had been a favourite uncle when he was Duke of Gloucester and Elizabeth couldn’t rid herself of the idea that he was kind and loving. He had explained away the absence of her brothers by blaming Buckingham and he implied in his proposal to her that his wife, her cousin Anne Neville, knowing she was dying, had virtually blessed the match, encouraging him to take another wife, one young and healthy, to give him more heirs. It works, more or less.

Schindler barely mentions this part of the story, dismissing it as rumour. And anyway, in January 1485, Richard let it be known he was pursuing a marriage with a Portuguese princess. Shortly after Anne’s funeral he made a public announcement that he had never intended to marry his niece. It looks remarkably as if he had flown a kite and been deterred by the negative public reaction.

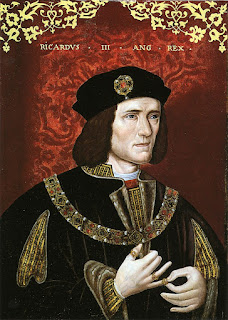

|

| Richard 111 |

Richard was famously defeated at the Battle of Bosworth Field and Henry Tudor claimed the throne by might and right. His claim was pretty tenuous, as, with the deaths of the princes and the impossibility of the young Earl of Warwick inheriting, since his father Clarence had been attainted as a traitor, the rightful heir was Elizabeth of York. Weir is excellent on this angle, with Elizabeth wanting to reign jointly with Henry and not just to strengthen his claim by their marriage. And marry him she did, though her coronation was put off for some years.

And what of John de la Pole, Richard’s heir presumptive as long as the Yorks were excluded by the parliament ruling that they were illegitimate? Although the new king imprisoned several Yorkists, he seems, as Schindler informs us to have taken rather a shine to John Jnr and given him positions at court. His trust soon proved misplaced, as Lincoln and his foster brother Francis Lovell were fiercely loyal to the dead Richard and were plotting Henry’s overthrow.

Some embryonic rebellions fizzled out but then the opportunity came with the claims of Lambert Simnel. Simnel was a Pretender from Ireland, who claimed to be the young Earl of Warwick. The problem was that Warwick was still imprisoned in the Tower. But the boy had been so well coached that Henry suspected another Yorkist was behind the plot and his eye fell on John Junior.

|

| Henry Vll |

Indeed, Weir does not buy Schindler’s notion that Henry found Lincoln trustworthy: “He means to be king, Bessy. I have suspected it all along.” Lincoln had fled to Burgundy under protection of the Duchess, Margaret, Elizabeth’s aunt, who seems to have been convinced by Simnel’s imposture. Simnel was crowned in Dublin as “King Edward” and Lincoln and Lovell’s forces joined and fought the king’s army at Stoke in June 1487.

It was to be fatal for Lincoln, who died fighting bravely, thwarting Henry of the chance to have him executed. The king took no revenge on John Senior but when he died and his son Edmund inherited the dukedom, Henry took back all John Junior’s possessions. Edmund was so short of funds that Henry demoted him from Duke to Earl and turned the whole family against him.

First Elizabeth John’s widow and then her sons Edmund and Richard fled to the Duchess of Burgundy. The unfortunate William was imprisoned in the Tower where he stayed till his death in 1539. Both his brothers continued to make attempts on the English thrones until their deaths.

Both books are handsomely produced, especially Alison Weir’s novel and both have the family trees, which are so essential to histories and, increasingly, to Historical novels. I think there is room for both for anyone as obsessed with the Plantagenets as I am.

No comments:

Post a Comment