This beautiful photograph is by my colleague David Winston, of whom I’ve written previously. It’s part of his recent London exhibition, Mood Indigo.

The image shows a shoal of

Venetian ferries, known as vaporetti, gliding down the Grand Canal with

minimal wake, humble stature and self-effacing lines. The vaporetti know

their place – it is to serve Venice: not to dominate her, not to reduce her to

a backdrop, not to repurpose her as a place to maximize alcohol sales and not

to do so at the cost of residents’ peaceful enjoyment of their homes nor at

possible risk to human and marine life.

Everyone’s the same on a

vaporetto. A vaporetto doesn’t care if you’re an influencer or a celebrity. And

even if you are one of the latter, please note that Venetian courtesy still

dictates that you give up your seat to an elderly person or a mother and baby.

The vaporetto is the right

vessel in the right place. Just as the Grand Canal is the perfect waterway,

protected from the commodification of greedy new skyscrapers and only occasionally

subject to tasteless advertising on shrouded scaffolds while her ancient

facades are restored.

If only the Thames were so lucky.

London’s greatest public realm, our river has suffered successive attempts at

commodification, like the Garden

Bridge and the River Park. Now we have (arguably) grotesque sky-grabs along the Thames,

with buildings like 72

Upper Ground

agglomerating ungainly masses from small footprints. Residential communities

are drained by successive campaigns against what is happening to the Thames,

which has become, as journalist Rowan Moore describes in the linked article,

Riparian development is controlled

by land-based authorities, but the river is ruled by the Port of London

Authority (PLA), operating on a 1909 charter and funded by the dues it extracts

from its client-vessels and its River Works licences.

When something goes wrong on the

river, however, it is not the PLA but the publicly funded emergency services

that must deal with it, as well as the RNLI, a charity.

Sadly, things do go wrong on the

Thames, especially given the swift 23ft tide and the intertwining of

industrial, commuter and traffic on a river that snakes as much as it flows.

And when things do go wrong, they

can go tragically wrong.

Most Londoners know about the 1989

Marchioness disaster, in which, at approximately 1.46am, the 262ft Bowbelle

dredger ran down an 85.5 ft party

boat near Southwark Bridge. The Marchioness sank in minutes. There were

51 casualties, most of them young. In subsequent hearings, safety, crew

training and lookouts on both vessels were judged inadequate.

Grieving families and friends

still gather in remembrance of the dead on the anniversary. Southwark Cathedral

hosts a permanent memorial to those lost. The Marchioness has remained a

household name for nearly thirty-five years.

But few people know about the Marine Accident Branch’s 2015

publication on the Marchioness disaster. Additional possible factors named in the report included: disco

music so loud that the captain couldn’t hear the radio warnings about the Bowbelle;

hydrodynamic interaction, by which two boats are drawn together, losing

steerability, especially in shallow, winding waterways.

And even fewer people know about

the river’s worst disaster so far, that of the Princess Alice. And that,

historians have theorized, is because most of those who died were poor. They

were ordinary Londoners, lacking celebrity except, briefly, for the hideous

manner of their deaths.

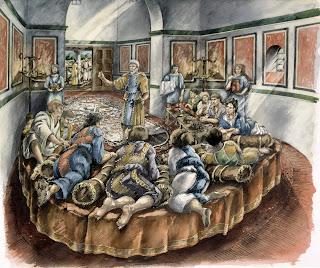

The PSS Princess Alice, a

paddle steamer, left Swan Lane Pier – by the northern foot of London Bridge –

in glorious sunshine on September 3rd, 1878. A long, low vessel, she

bore a crowd of around 800 Londoners on a pleasure excursion to the Rosherville

Pleasure Gardens at Northfleet, Gravesend and Sheerness. The Princess Alice’s

owners, the London Steam Company, operated a kind of hop-on hop-off system with

its other ships so no one knows how many passengers joined the vessel that

evening for the ‘moonlight trip’ home.

Entertainment continued all the

way back, with the band playing on deck. The sun had set and the moon was

rising around 7.30pm when, near Gallions Reach, the Princess Alice (219ft)

was rammed in the starboard side by the SS Bywell Castle, a cargo ship (254

ft).

In less than four minutes, the Princess

Alice broke into three and sank. Her deck passengers were pitched into

water horribly enriched by gallons of raw sewage. Those below decks were entombed

inside the doomed vessel.

Nick Higham’s The Mercenary River explains how Joseph Bazalgette, for the Metropolitan Board of Works, had in the previous decades diverted the sewage of London to the eastern reaches of the city. In a vivid chapter, ‘Volcanoes of Filth’, Higham recounts how cost considerations stopped the sewage outfalls being sited far enough from the metropolis. At the time of the tragedy, two grand pumping stations churned out London’s waste twice a day at Barking and Crossness. The Princess Alice had come to grief at Tripcock Point, too close in time and place to the evening’s discharge of millions of gallons of untreated waste – not just human but also oil, petroleum and the liquids drained from abattoirs and factories.

In the minutes after impact, a few

male passengers from the Princess Alice were able to climb up the Bywell’s

ropes or use the life-buoys, chicken-coops and chairs thrown down to them. But,

like the captain of the Bowbelle in 1989, the Bywell’s master

chose not to stay long on the scene to help rescue victims. Instead, he steamed

away. In the dark, in the foetid water, around 650 drowned. Few women made it

to shore alive. Impeded by their long skirts, women were also far less likely

than the male passengers to know how to swim. At the moment the Bywell

struck, many women were below decks, tending to their children. The young fared

badly too. Among the dead and missing were 95 children of twelve and under as

well as 30 babies aged 15 months or less. A diver investigating the wreck a few

days later found bodies packed, vertical, near the doors through which they

were probably trying to escape.

Of the Princess Alice’s

passengers, just 130 survived. More than a dozen of those died soon after,

possibly from ingesting the foul water.

As the news seeped out, Londoners

made the grim pilgrimage to Woolwich to claim their dead, who were now being

washed up at different points along the Thames. The mourners were accompanied

by journalists, newspaper artists (whose work you see here) and tragedy

tourists, some of whom – in a queasy pre-echo of today’s clamorous social media

– felt obliged to inundate the newspapers and the coroner’s post-box with

‘helpful’ letters about the best way to manage the gruesome situation.

Only gradually was a ghost passenger

list compiled, never to this day completed. We know now that it included 46 out

of 51 members of the Clerkenwell Mission Bible Class and eight pupils from the

Queen’s College Institution for Young Ladies. The professions of the dead

sketched their social classes: zinc plate worker, coach trimmer, caulker,

commercial traveller, servant, nursemaid, tobacconist, greengrocer,

ironmonger’s porter, pipe maker, sweet-seller, shoemaker, draper’s assistant,

rising to solicitor’s clerk, organist and the mistress of Limehouse Industrial

School.

The police found an ingenious way

to spare relatives the pain of inspecting hundreds of corpses – in

deteriorating condition – when searching for their loved ones. Trinkets and

valuables were put in numbered glass-topped cigar-boxes. Shawls and other items were hung up, also

with the same numbers. Clothes taken from bodies were boiled and then sewn

together so they could not be scattered. Only relatives who recognised the

possessions would be taken to view and identify the body with the corresponding

number.

Many of the drowned were buried as

‘unknown’. Ten were later exhumed at the expense of their families. But most of

the anonymous dead remained unclaimed, listed only by the colour of their hair

and sometimes their height. Among them were 18 children, including infants.

Perhaps eighty people were never

recovered from the river. Family historian Colin Aylsbury has put online a list

of the dead, the saved and the missing here. And this

Facebook page serves as a meeting place for people who are descended from Princess

Alice victims, crew, survivors and the Lightermen who collected the corpses

from the Thames.

Although it’s largely forgotten now, for some months personal accounts, funerals and scandals kept the Princess Alice tragedy in the press and in the courts. The captain of the Princess Alice had died in the accident, and with him the truth about the last minutes of his vessel. Various court cases blamed first the Bywell Castle and later the Princess Alice, for wrong steers and misleading signalling. There were accusations of drunkenness against the Bywell’s crew. Some said that the cargo vessel’s engine had not been cut, thus failing to prevent its propellor from injuring flailing victims. Some Lightermen, who collected the bodies for five shillings apiece, were denounced for rifling their valuables or piling them up so that the dead were further disfigured; there were stories of alcohol-fuelled fights over corpses. The Lighterman also earned by rowing sightseers out to the wreck.

Some of the scandals are recounted in this eight-page pamphlet below, from Wikimedia Commons. It describes its contents as follows: ‘An Authentic Narrative by a Survivor, not hitherto published. Heartrending Details - Facts not made public - Noble efforts to save life - Robbing the Dead - Particulars as to lost, saved, and missing - Plan of the Locality. Sketches by an eye-witness. Beautiful Poem, specially written on the event, now first published. Memorial for all time of this fearful calamity.’

The coroner concluded that the Princess Alice was not properly or efficiently manned, lacked adequate life-saving equipment and was probably overloaded with passengers. There were also claims that the Princess Alice’s design had sealed her fate. Her length was 28 times her draught, rendering her riskily top-heavy. Nevertheless, the vessel had been passed by the Board of Trade in 1878 to carry maximum of 936 passengers between London and Gravesend in smooth conditions.

Where Venice has its vaporetti,

and London has its Clippers, today’s Thames also hosts a fleet of around 60

leisure boats, most of which offer beautiful days or evenings on the river at

reasonable costs. Certainly, there’s a problem with thundering music, bellowing

DJs and shouting passengers. However, the 1200 complaints registered in the

last year focussed on just a very small number of vessels. The vast majority

cause harm to no one and give pleasure to thousands.

But the Thames horizon may be

about to change, with the arrival of a massive new ‘floating events space’.

Last summer the Oceandiva

consortium applied for a 2.30/3am liquor licence and also bought control of two

old Thameside piers – Butler’s Wharf (below) and West India Pier.

Butler’s Wharf, designated in some

Oceandiva’s publicity as its ‘main residence’, is surrounded by around 5000

residents; close by are two communities of boat-dwellers including dozens of

children. Diagonally across the river is the Tower of London, where 100 people

live.

Meanwhile, tiny West India Pier (above) was abandoned and derelict for years, during which time a community of around

700 residents grew up around the site, which is served by a single narrow

street. Now West India Pier is slated for transformation into a high-voltage

charging, telecoms and servicing station.

In the two riparian communities,

the shock is palpable.

Elsewhere, Londoners have been frank, if not brutal, when it comes to their opinions of the ‘super-yacht’s size, design and its designs on the city’s public realm. ‘I've seen better looking coal barges,’ observed one reader of the Daily Mail. Another said, ‘That ship would give me the creeps. Cold, dark, uninviting, and creepy.’ Others expressed fears that London’s emergency services lack adequate capacity to deal with an Oceandiva-sized emergency: ‘It's another Marchioness waiting to happen.’

Meanwhile, no one (except perhaps

the Oceandiva consortium) knows exactly when the vessel will arrive on

the Thames. Last week, the consortium withdrew their liquor licence

application, citing construction/certification delays, but stating that they

will re-apply in the near future.

The sudden withdrawal of the liquor licence application cancels out the 1000 objections that were made within the deadline last October.

Michelle Lovric’s website

OTHER LINKS

River Residents Group website

Petition · The Ocean Diva party boat will ruin the most historic part of the Thames · Change.org

Petition · No OceanDiva · Change.org

Princess Alice Memorial, Woolwich

Cemetery: https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/2985013

Royal Museums Greenwich: https://www.rmg.co.uk/stories/blog/library-archive/drowning-sewage-sinking-princess-alice

Art in the Docks commissioned a moving collaboration between artist Christopher Mike and sculptor Vincenzo Muratore to commemorate those lost on the Princess Alice. You can see images here.