To win a copy of Helen Peters' Anna at War, just answer the following question in the Comment section:

"Towards the end of Anna at War, Anna has a very dramatic encounter with Winston Churchill. If you had the chance to meet any famous historical figure, who would you choose and why?"

Then copy your answers in an email to this address: maryhoffman@maryhoffman.co.uk

Closing date 7th July

We are sorry that our competitions are open to UK Followers only.

Good luck!

Sunday, 30 June 2019

June Competition

Saturday, 29 June 2019

Finding the Story from the Research by Helen Peters

Our June guest is Helen Peters.

Helen Peters grew up on an old-fashioned farm in Sussex, surrounded by family, animals and mud. She spent most of her childhood reading stories and putting on plays in a tumbledown shed that she and her friends turned into a theatre. After university, she became an English and Drama teacher. Helen lives with her husband and children in London, and she can hardly believe that she now gets to call herself a writer.

Anna at War started in a different way from any of my previous books. I had just finished Evie’s Ghost, a timeslip story about a modern girl who goes to stay in an old house and finds herself taken back to 1814, when my editor asked if I would like to write another historical novel. So I found myself in the interesting and slightly daunting position of being able to choose any period of history, anywhere in the world.

While I was wondering what and when to write about, I started rereading Anne Frank’s diary, in preparation for teaching autobiographical writing to my Year 7 English class. I hadn’t read the book since I was a teenager, and I was astounded by it all over again. The vividness of Anne’s writing and her courage and resilience really struck me, and I began to think about writing a story about a girl’s experience in World War 2.

At around the same time, two women in their nineties separately contacted my husband, who is the head teacher of a boarding school in Brighton. They both wanted to thank the school that, eighty years ago, had taken them in as Jewish refugees from Nazi-occupied Europe. One of them remembered how her father, as he put her on the train, had cut off her plaits, thinking that if she could pass as a boy she might be safer on the journey. “I travelled all the way to England,” she said, “with my pigtails in my pockets.” The other talked about the ‘remarkable’ concern shown by the headmistress for ‘the terrorised young innocent girl who arrived in Brighton’. She wrote: ‘The British were so magnanimous to welcome us foreigners… truly showing a phenomenal humanity.’

This sentence really struck me, at a time when so much media coverage seems to dehumanise refugees. These stories cemented my desire to write about a girl who comes to England as a refugee from Nazi Germany. But I was very anxious about doing this. What right did I have, as a non-Jewish Englishwoman who has never experienced persecution, to write about the horrors of being a Jewish child in Nazi Germany?

The obvious solution seemed to be to write the story from the point of view of an English girl who befriends a refugee girl at her boarding school. This was the idea I had in mind when I began to research the Kindertransport, the coordinated rescue effort that brought ten thousand unaccompanied children from Nazi-occupied Europe to England between December 1938 and August 1939.

I knew very little about the Kindertransport before I began my research, so I started by watching documentaries and reading introductions to the subject. Once I had an overview, I started devouring autobiographies and memoirs of Kindertransportees.

While I was researching, I was also trying to find my story. I knew I wanted the two girls, Anna and Molly, to become friends, and I knew I wanted them to have some sort of adventure together, but I wasn’t sure what.

I started to write the story from Molly’s point of view but, after writing a few terrible scenes, I realised two things. Firstly, every time I tried to set a scene in a 1930s boarding school, my writing instantly descended into cliché and my characters became appalling cartoonish stereotypes. My knowledge of pre-war boarding schools is entirely gleaned from Enid Blyton and Angela Brazil. If I were going to write about one, I would need to do a lot more research.

I didn’t do this research, because the second thing I discovered was that I was far more interested in Anna’s story than Molly’s. So I tentatively started to write some scenes from Anna’s point of view.

Many of the Kindertransportees vividly remembered their journey to England by train and boat, and many of their memories were very similar, so I began by writing about Anna’s journey, which was very closely based on these memories.

I was particularly taken by the recollections of Emmy Mogilensky, who was fifteen when she travelled to England. Emmy’s train was about to leave the station when a wicker basket was shoved into her compartment. She opened the basket to find twin babies inside. There were bottles and nappies in the basket, but no documentation, so the babies had obviously not been officially registered for the Kindertransport. Emmy looked after them on the journey and refused to allow them to be taken to an orphanage in Holland, thus unknowingly saving their lives. Mrs Mogilensky died in 2017, but luckily she gave a detailed interview to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Oral History Archive, which is freely available online. Her story was the main inspiration for Anna’s journey.

Many children also had vivid memories of the horrors of Kristallnacht, when their houses and flats were smashed up by Nazi storm troopers and their fathers were arrested and taken to concentration camps. I wrote scenes set on Kristallnacht, too. At this point, I wasn’t sure whether I would tell the story chronologically, or whether the book would open at the point where Anna and Molly meet, and Anna’s journey to England would be told in flashbacks. I decided not to fret about the structure, but just to write individual scenes, trusting that the right sequence would become obvious once I had finished the first draft. I’d never written a draft in this way before, and it felt very freeing.

I still hadn’t decided what adventure Anna and Molly would have together. But then, as I was researching details of children’s lives in wartime rural England, I discovered the fascinating BBC People’s War website, which contains written accounts by people from all over the UK of their lives during World War Two. I searched under ‘Children’ and found a piece called ‘When the Army Came to Stay’, by a woman called Pamela Hoath, who was the chauffeur’s daughter on a large Kent estate when the whole estate was taken over by the army. There was great excitement when the residents heard that Field Marshall Montgomery was coming to live in the Dower House, to oversee the training of the troops.

I also discovered online a facsimile of If The Invader Comes, a leaflet that was sent to every household in Britain in June 1940. The leaflet is written as a series of statements, instructions and orders, including such instructions as ‘Do Not Give Any German Anything.’

This leaflet and Pamela Hoath’s memories gave me the final piece of my story. Anna would be fostered by Molly’s family. Molly would be the daughter of the carpenter on a large country estate in Kent that is suddenly taken over by the army. So Anna, who has travelled all the way from Frankfurt to apparent safety in England, suddenly finds herself surrounded by soldiers again, at the very time when ‘enemy aliens’ are being sent to internment camps and the whole country has been warned not to trust a German. When she and Molly discover a strange man in their barn, Anna will have to use all her courage, resilience and ingenuity to face the challenges ahead.

Helen Peters grew up on an old-fashioned farm in Sussex, surrounded by family, animals and mud. She spent most of her childhood reading stories and putting on plays in a tumbledown shed that she and her friends turned into a theatre. After university, she became an English and Drama teacher. Helen lives with her husband and children in London, and she can hardly believe that she now gets to call herself a writer.

Anna at War started in a different way from any of my previous books. I had just finished Evie’s Ghost, a timeslip story about a modern girl who goes to stay in an old house and finds herself taken back to 1814, when my editor asked if I would like to write another historical novel. So I found myself in the interesting and slightly daunting position of being able to choose any period of history, anywhere in the world.

While I was wondering what and when to write about, I started rereading Anne Frank’s diary, in preparation for teaching autobiographical writing to my Year 7 English class. I hadn’t read the book since I was a teenager, and I was astounded by it all over again. The vividness of Anne’s writing and her courage and resilience really struck me, and I began to think about writing a story about a girl’s experience in World War 2.

At around the same time, two women in their nineties separately contacted my husband, who is the head teacher of a boarding school in Brighton. They both wanted to thank the school that, eighty years ago, had taken them in as Jewish refugees from Nazi-occupied Europe. One of them remembered how her father, as he put her on the train, had cut off her plaits, thinking that if she could pass as a boy she might be safer on the journey. “I travelled all the way to England,” she said, “with my pigtails in my pockets.” The other talked about the ‘remarkable’ concern shown by the headmistress for ‘the terrorised young innocent girl who arrived in Brighton’. She wrote: ‘The British were so magnanimous to welcome us foreigners… truly showing a phenomenal humanity.’

This sentence really struck me, at a time when so much media coverage seems to dehumanise refugees. These stories cemented my desire to write about a girl who comes to England as a refugee from Nazi Germany. But I was very anxious about doing this. What right did I have, as a non-Jewish Englishwoman who has never experienced persecution, to write about the horrors of being a Jewish child in Nazi Germany?

The obvious solution seemed to be to write the story from the point of view of an English girl who befriends a refugee girl at her boarding school. This was the idea I had in mind when I began to research the Kindertransport, the coordinated rescue effort that brought ten thousand unaccompanied children from Nazi-occupied Europe to England between December 1938 and August 1939.

I knew very little about the Kindertransport before I began my research, so I started by watching documentaries and reading introductions to the subject. Once I had an overview, I started devouring autobiographies and memoirs of Kindertransportees.

While I was researching, I was also trying to find my story. I knew I wanted the two girls, Anna and Molly, to become friends, and I knew I wanted them to have some sort of adventure together, but I wasn’t sure what.

I started to write the story from Molly’s point of view but, after writing a few terrible scenes, I realised two things. Firstly, every time I tried to set a scene in a 1930s boarding school, my writing instantly descended into cliché and my characters became appalling cartoonish stereotypes. My knowledge of pre-war boarding schools is entirely gleaned from Enid Blyton and Angela Brazil. If I were going to write about one, I would need to do a lot more research.

I didn’t do this research, because the second thing I discovered was that I was far more interested in Anna’s story than Molly’s. So I tentatively started to write some scenes from Anna’s point of view.

Many of the Kindertransportees vividly remembered their journey to England by train and boat, and many of their memories were very similar, so I began by writing about Anna’s journey, which was very closely based on these memories.

I was particularly taken by the recollections of Emmy Mogilensky, who was fifteen when she travelled to England. Emmy’s train was about to leave the station when a wicker basket was shoved into her compartment. She opened the basket to find twin babies inside. There were bottles and nappies in the basket, but no documentation, so the babies had obviously not been officially registered for the Kindertransport. Emmy looked after them on the journey and refused to allow them to be taken to an orphanage in Holland, thus unknowingly saving their lives. Mrs Mogilensky died in 2017, but luckily she gave a detailed interview to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Oral History Archive, which is freely available online. Her story was the main inspiration for Anna’s journey.

Many children also had vivid memories of the horrors of Kristallnacht, when their houses and flats were smashed up by Nazi storm troopers and their fathers were arrested and taken to concentration camps. I wrote scenes set on Kristallnacht, too. At this point, I wasn’t sure whether I would tell the story chronologically, or whether the book would open at the point where Anna and Molly meet, and Anna’s journey to England would be told in flashbacks. I decided not to fret about the structure, but just to write individual scenes, trusting that the right sequence would become obvious once I had finished the first draft. I’d never written a draft in this way before, and it felt very freeing.

I still hadn’t decided what adventure Anna and Molly would have together. But then, as I was researching details of children’s lives in wartime rural England, I discovered the fascinating BBC People’s War website, which contains written accounts by people from all over the UK of their lives during World War Two. I searched under ‘Children’ and found a piece called ‘When the Army Came to Stay’, by a woman called Pamela Hoath, who was the chauffeur’s daughter on a large Kent estate when the whole estate was taken over by the army. There was great excitement when the residents heard that Field Marshall Montgomery was coming to live in the Dower House, to oversee the training of the troops.

I also discovered online a facsimile of If The Invader Comes, a leaflet that was sent to every household in Britain in June 1940. The leaflet is written as a series of statements, instructions and orders, including such instructions as ‘Do Not Give Any German Anything.’

This leaflet and Pamela Hoath’s memories gave me the final piece of my story. Anna would be fostered by Molly’s family. Molly would be the daughter of the carpenter on a large country estate in Kent that is suddenly taken over by the army. So Anna, who has travelled all the way from Frankfurt to apparent safety in England, suddenly finds herself surrounded by soldiers again, at the very time when ‘enemy aliens’ are being sent to internment camps and the whole country has been warned not to trust a German. When she and Molly discover a strange man in their barn, Anna will have to use all her courage, resilience and ingenuity to face the challenges ahead.

Friday, 28 June 2019

Rooted out, destroyed and abolished? From the Inquisition to a cosy English Bed and Breakfast. By Ruth Downie

“These poisonous growths in the church of God must be torn up by the roots lest they spread themselves further.” - Pope Urban VIII

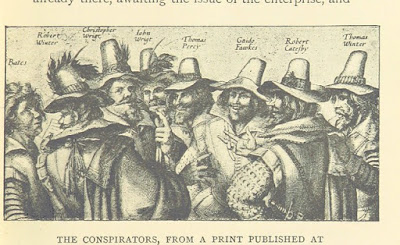

Mary Ward’s idea for a female religious order inspired by the Jesuits was not popular in Rome. It wasn’t popular in her native England either. The Gunpowder Plot was still within living memory, and two of Mary’s uncles had been amongst the plotters. They're shown in the engraving below: Christopher and John Wright, third and fourth from the left. Suspicion of Roman Catholics was rife. This was an age of secret Masses: of underground priests, of spies, tortures and executions.

Mary originally escaped the turmoil in England by joining a convent in St Omer, but found herself dissatisfied with the cloistered life that was demanded of women devoted to the church. She was convinced that God wanted her to do more.

“There is no such difference between men and women,” she wrote, “that women may not do great things.”

Returning to London, she established an undercover group of women who offered education, encouragement and practical support to persecuted Roman Catholics both in and out of prison. Confident that God wanted her to create an order of women who were free to travel and do his will wherever they went, she and a small group of sisters walked all the way to Rome to seek the Pope’s approval. Here’s a replica of the hat she wore for the journey:

Unfortunately Mary was not skilled in church politics, and the church was not skilled in communication. Not realising that the long silence from the Pope meant ‘no’, she went ahead, setting up groups of “Jesuitesses” who ran schools and communities in several European cities. Upon hearing rumours that the Church did not approve and that her groups were being disbanded, she wrote urging her colleagues in Trier, Cologne and Liege to ignore any orders of suppression. She was certain the Pope could not have authorised any such instruction.

Unfortunately Mary was not skilled in church politics, and the church was not skilled in communication. Not realising that the long silence from the Pope meant ‘no’, she went ahead, setting up groups of “Jesuitesses” who ran schools and communities in several European cities. Upon hearing rumours that the Church did not approve and that her groups were being disbanded, she wrote urging her colleagues in Trier, Cologne and Liege to ignore any orders of suppression. She was certain the Pope could not have authorised any such instruction.

The letter was more naïve than heretical, but the damage was done. This was disobedience, and disobedience had to be dealt with. The Inquisition was called in, and Mary was imprisoned while the church decided what should be done with her.

Mary seems to have been remarkably longsuffering in her imprisonment. But while she co-operated with the authorities on the surface, she also kept up a secret correspondence with her friends on the outside. As every schoolchild knows, but apparently Mary’s guardians didn’t, lemon juice dries invisible but can be revealed by warming the paper.

In the end she was not convicted of heresy, but neither was she fully freed. Her groups of “Jesuitesses” were ordered to be broken up and banned forever. As Urban VIII put it in his Papal Bull of 1631, they had been guilty of wandering about at will, “and under the guise of promoting the salvation of souls, have been accustomed to attempt and to employ themselves at many other works which are most unsuited to their weaker sex and character, to female modesty and particularly to maidenly reserve.” Furthermore they persisted in such activities, and were “not ashamed”.

Mary died with her life’s work apparently in ruins. However - some of the communities she founded managed to hang on by the skin of their teeth, although they were not allowed to acknowledge her as their founder.

With no official support they were desperately poor, so it was a great relief to the group in York when Thomas Gascoigne, a member of the local Catholic gentry, declared, “We must have a school for our daughters,” and put up £450 to fund it. Mother Frances Bedingfield, acting in the true spirit of Mary Ward with the lemon juice, purchased a building under a false name, and thus established the first convent in England since Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries.

The Bar Convent is still there: just around the corner from York station and close to the city walls. The sisters who live there belong to an order now called the Congregation of Jesus. They and their predecessors ran the school for almost 300 years, surviving the suspicious searches of officials, a rampaging mob (St Michael was apparently instrumental in seeing them off) and the threat of prosecution for non-attendance at Holy Communion in the local Anglican church. (The case failed when it turned out that the vicar hadn’t bothered to hold a service on the day in question.)

The convent has given sanctuary to refugees fleeing the French Revolution, to Belgian children and convalescing soldiers in the First World War, and to Bosnian children during the Balkan conflict.

The convent has given sanctuary to refugees fleeing the French Revolution, to Belgian children and convalescing soldiers in the First World War, and to Bosnian children during the Balkan conflict.

It has also provided a discreet place of worship for Roman Catholics unwilling to surrender to the Church of England. The chapel, built in the 1760’s, is invisible from the outside of the building. I can vouch for the fact that its eight exits (in case a quick escape was needed) are very confusing to outsiders. There's also a hiding-place for the celebrant - a “priest’s hole” - which I never found.

The convent has now survived the departure of the school, which moved elsewhere in the 1980’s. Seeking a new use for the building that would allow it to cover its costs, the Congregation of Jesus hit upon hospitality - and this is where people like me come in.

The Bar Convent now offers a Bed and Breakfast refuge for visitors to the beautiful but exhausting city of York. It’s a peaceful haven with enclosed gardens, a stunning glass-roofed Victorian courtyard, a guests’ kitchen, a teashop, and a museum that’s well worth a visit. I stayed there earlier this month for the York Roman Festival and have already booked again for next year.

As for Mary Ward - the orders she established were finally allowed to acknowledge her as founder in 1909. A hundred years later, Pope Benedict XVI published a decree recognising her “heroic virtue”. She is, apparently, on the path to sainthood.

Finally, Mary Ward’s time has come.

Sources -

Bar Convent Heritage Centre website

Bar Convent information leaflet

Mary Ward - Under the Shadow of the Inquisition, by M. Immolata Wetter

The History of the Bar Convent by Sister Gregory IBVM,

Mary Ward by Sr Gregory Kirkus CJ

Any and all errors are Ruth's own!

Ruth Downie writes murder mysteries set in Roman Britain - find out more at www.ruthdownie.com

Eboracum Roman Festival is a splendid weekend for anyone interested in anything remotely Roman. Ruth's account of it is here. The next one will be held in York on 29-31 May 2020. If you want to stay at the convent, book now!

Mary Ward’s idea for a female religious order inspired by the Jesuits was not popular in Rome. It wasn’t popular in her native England either. The Gunpowder Plot was still within living memory, and two of Mary’s uncles had been amongst the plotters. They're shown in the engraving below: Christopher and John Wright, third and fourth from the left. Suspicion of Roman Catholics was rife. This was an age of secret Masses: of underground priests, of spies, tortures and executions.

Mary originally escaped the turmoil in England by joining a convent in St Omer, but found herself dissatisfied with the cloistered life that was demanded of women devoted to the church. She was convinced that God wanted her to do more.

“There is no such difference between men and women,” she wrote, “that women may not do great things.”

Returning to London, she established an undercover group of women who offered education, encouragement and practical support to persecuted Roman Catholics both in and out of prison. Confident that God wanted her to create an order of women who were free to travel and do his will wherever they went, she and a small group of sisters walked all the way to Rome to seek the Pope’s approval. Here’s a replica of the hat she wore for the journey:

Unfortunately Mary was not skilled in church politics, and the church was not skilled in communication. Not realising that the long silence from the Pope meant ‘no’, she went ahead, setting up groups of “Jesuitesses” who ran schools and communities in several European cities. Upon hearing rumours that the Church did not approve and that her groups were being disbanded, she wrote urging her colleagues in Trier, Cologne and Liege to ignore any orders of suppression. She was certain the Pope could not have authorised any such instruction.

Unfortunately Mary was not skilled in church politics, and the church was not skilled in communication. Not realising that the long silence from the Pope meant ‘no’, she went ahead, setting up groups of “Jesuitesses” who ran schools and communities in several European cities. Upon hearing rumours that the Church did not approve and that her groups were being disbanded, she wrote urging her colleagues in Trier, Cologne and Liege to ignore any orders of suppression. She was certain the Pope could not have authorised any such instruction. The letter was more naïve than heretical, but the damage was done. This was disobedience, and disobedience had to be dealt with. The Inquisition was called in, and Mary was imprisoned while the church decided what should be done with her.

Mary seems to have been remarkably longsuffering in her imprisonment. But while she co-operated with the authorities on the surface, she also kept up a secret correspondence with her friends on the outside. As every schoolchild knows, but apparently Mary’s guardians didn’t, lemon juice dries invisible but can be revealed by warming the paper.

In the end she was not convicted of heresy, but neither was she fully freed. Her groups of “Jesuitesses” were ordered to be broken up and banned forever. As Urban VIII put it in his Papal Bull of 1631, they had been guilty of wandering about at will, “and under the guise of promoting the salvation of souls, have been accustomed to attempt and to employ themselves at many other works which are most unsuited to their weaker sex and character, to female modesty and particularly to maidenly reserve.” Furthermore they persisted in such activities, and were “not ashamed”.

Mary died with her life’s work apparently in ruins. However - some of the communities she founded managed to hang on by the skin of their teeth, although they were not allowed to acknowledge her as their founder.

|

| The Bar Convent |

The Bar Convent is still there: just around the corner from York station and close to the city walls. The sisters who live there belong to an order now called the Congregation of Jesus. They and their predecessors ran the school for almost 300 years, surviving the suspicious searches of officials, a rampaging mob (St Michael was apparently instrumental in seeing them off) and the threat of prosecution for non-attendance at Holy Communion in the local Anglican church. (The case failed when it turned out that the vicar hadn’t bothered to hold a service on the day in question.)

The convent has given sanctuary to refugees fleeing the French Revolution, to Belgian children and convalescing soldiers in the First World War, and to Bosnian children during the Balkan conflict.

The convent has given sanctuary to refugees fleeing the French Revolution, to Belgian children and convalescing soldiers in the First World War, and to Bosnian children during the Balkan conflict. It has also provided a discreet place of worship for Roman Catholics unwilling to surrender to the Church of England. The chapel, built in the 1760’s, is invisible from the outside of the building. I can vouch for the fact that its eight exits (in case a quick escape was needed) are very confusing to outsiders. There's also a hiding-place for the celebrant - a “priest’s hole” - which I never found.

The convent has now survived the departure of the school, which moved elsewhere in the 1980’s. Seeking a new use for the building that would allow it to cover its costs, the Congregation of Jesus hit upon hospitality - and this is where people like me come in.

The Bar Convent now offers a Bed and Breakfast refuge for visitors to the beautiful but exhausting city of York. It’s a peaceful haven with enclosed gardens, a stunning glass-roofed Victorian courtyard, a guests’ kitchen, a teashop, and a museum that’s well worth a visit. I stayed there earlier this month for the York Roman Festival and have already booked again for next year.

|

| The Victorian glazed courtyard dining area |

Finally, Mary Ward’s time has come.

Sources -

Bar Convent Heritage Centre website

Bar Convent information leaflet

Mary Ward - Under the Shadow of the Inquisition, by M. Immolata Wetter

The History of the Bar Convent by Sister Gregory IBVM,

Mary Ward by Sr Gregory Kirkus CJ

Any and all errors are Ruth's own!

Ruth Downie writes murder mysteries set in Roman Britain - find out more at www.ruthdownie.com

Eboracum Roman Festival is a splendid weekend for anyone interested in anything remotely Roman. Ruth's account of it is here. The next one will be held in York on 29-31 May 2020. If you want to stay at the convent, book now!

Labels:

Bar Convent,

Eboracum Roman Festival,

gunpowder plot,

Inquisition,

Mary Ward,

Ruth Downie,

York

Thursday, 27 June 2019

Greyhound Racing by Janie Hampton

|

| 18th century racing greyhound |

My lovely Millicent Magic came last and I lost one pound. Was the trip to Swindon Greyhound Race Track worth a few seconds of excitement? For thousands of people in Britain, greyhound racing has been their world, their life: as trainers, owners, bookmakers, kennel hands and punters.

In 1926, greyhound racing was introduced from the USA to Manchester, England. Within a few weeks over 11,000 spectators attended each Belle Vue meeting and two years later there were 68 tracks around England. There was not much else for the working man to do, and it was a cheap night out.

|

“Jock the Thief” was a regular at the Wimbledon track in the 1950s. ‘He always came with a big suitcase,’ remembers Newman. ‘It was stuffed with razors, shirts, silk ties, ladies stockings, scarves, perfume –things that were difficult to get. He sold them out of his suitcase at knock-down prices but nobody asked questions. By the time the races started he had sold the lot. He then proceeded to lose it all on the dogs. Next week, he was back, with another suitcase full.’

|

|

| 'Running in field', painting by Charles Hampton. |

‘In the old days,’ said Gilly Hepden, ‘rich people raced horses and poor people had dogs. Now dogs are owned by all types.’ A greyhound costs anything from £500 up to £40,000 and then £50 a week to train. ‘You never make your money back, that isn’t the idea. People do it for the love of dogs, and the other people who love dogs.’

|

|

| The author with Dylan, a rescue greyhound-cross, or lurcher. The Retired Greyhound Trust rehomes nearly 4,000 dogs a year, funded by a levy from bookmakers. |

Greyhound Board of Great Britain

Retired Greyhound Trust

Swindon Greyhound Track

www.janiehampton.co.uk

A version of this article originally appeared in The Oldie magazine.

Labels:

Bette Davis,

Greyhound,

Janie Hampton,

London,

Oxford,

racing,

Roger Moore,

Swindon,

Towcester,

Walthamstow,

White City,

Winston Churchill

Wednesday, 26 June 2019

The Eiffel Tower celebrates 130 years, by Carol Drinkwater

Sunrise seen from the Eiffel Tower

This year in France, our very own Iron Lady has reached her 130th birthday. Le Tour Eiffel. Receiving close to 7 million visitors a year, it is the most visited monument in the world, but like so many other artistic endeavours it was not an easy birth. The plan to build a 300 metre high, iron construction was conceived as part of the celebrations for the World Fair of 1889, exactly one hundred years after the French Revolution.

The idea, its concept was met with some enthusiasm and a great deal of anger, mockery and vitriol.

Many from the world of arts and letters, including Guy de Maupassant, Alexandre Dumas junior, Charles Gounod, began in 1886 to campaign against an iron construction. Such a monstrosity, they argued, would overshadow the capital's iconic monuments. Pamphlets and articles were published. These were known collectively as La Protestations des Artistes. Charles Garnier, the renowned architect who designed the Paris Opera House and had collaborated with Gustave Eiffel on the magnificent dome of the Observatoire in Nice, was also amongst them. Paul Verlaine described the design as a "belfry skeleton". Others were far less kind.

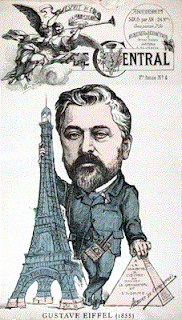

Caricature of Gustave Eiffel published in 1887 at the time of "The Artists' Protest"

Gustave's response to the criticism was:

"Do you think it is for their artistic value that the pyramids have so powerfully struck the imagination of men? What are they, after all, but artificial mountains? [The aesthetic impact of the pyramids was found in] the immensity of the effort and the grandeur of the result. My tower will be the highest structure that has ever been built by men. Why should that which is admirable in Egypt become hideous and ridiculous in Paris?"

In spite of the vociferous objections, the drilling and digging work for the foundations began on 28th January 1887. Remarkably, the tower was completed on 31st March 1889. It was a feat of engineering genius. That same year, for the World Fair, two million people visited the tower rising proudly skywards from the Champs-de-Mars.

18th July 1887

7th Dec 1887

26th Dec 1988

"A thick cloud of tar and coal smoke seized the throat, and we were deafened by the din of metal screaming beneath the hammer. Over there they were still working on the bolts: workmen with their iron bludgeons, perched on a ledge just a few centimetres wide, took turns at striking the bolts (these in fact were the rivets). One could have taken them for blacksmiths contentedly beating out a rhythm on an anvil in some village forge, except that these smiths were not striking up and down vertically, but horizontally, and as with each blow came a shower of sparks, these black figures, appearing larger than life against the background of the open sky, looked as if they were reaping lightning bolts in the clouds."

The tenth Exposition Universelle was held in Paris from 15th May to 6th November 1889. It was for this occasion that the tower had been conceived and built. The Exposition stretched over 95 hectares filling the Champ-de-Mars, Trocadero Hill and the banks all the way to the Invalides esplanade. The Eiffel Tower, at that stage the tallest structure in the world, dominated all of it. Those who had written and railed against it were silenced. This work of engineering genius, this architectural masterpiece, was a huge success. It drew crowds from all over the world and was intended to remain in situ for twenty years. That was 130 years ago.

Le Figaro, the French daily newspaper, set up a writing press on its second floor from where it produced a special edition of the paper.

Another rather wonderful attraction proposed to the visiting public was 'Print and Send Your Letters by Balloon'. "Printed on the Eiffel Tower". The Figaro reported "the Tower's company is doing its utmost to increase the number of attractions in favour of its clientele. It has just decided to put up for sale, on all the Tower's floors, small balloons and cheap parachutes arranged in such a way that one can attach a letter to them. The sender's address will be left blank. We wish the Tower's parachutes the same success as its postcards."

So many book ideas come flying into my mind when I read this!

The Eiffel Tower also played an important role in the popularity of the postcard as a form of communication.

Here is an Eiffel Tower post card by Libonis. It is named after the famous engraver.

This one above is dated October 1889. I have no idea of its value today.

It was a year of festivities for the fair, the Exposition. Thousands and thousands of visitors flooded the city, crowding into the fair, and the high spirits were contagious. The tower was lit up every evening with hundreds of gas lamps. A tricolour beacon housed in the campanile sent out three signals: blue, white, and red. These illuminations could be seen all across Paris. A baker on stilts from the Landes region climbed the entire 347 steps that led to the first floor!

Gustave Eiffel December 1832 - December 1923

I am inspired by this man's story. His determination against all the odds, the criticism from many of the finest minds in the land, to build his tower, to see his vision through.

This year, if you are in Paris, even if you have visited the Eiffel Tower before, do pay it another few hours of your time. There are celebrations on every level, special restaurant offerings, walk its gardens and remember the man, the genius, who fought for its existence. You can even visit Gustave's office on the top floor where you will find the figure of him with the American inventor, Thomas Edison, who paid Gustave a visit there and offered him one of his own inventions, a phonograph.

An uplifting story relates how Gustave on 10th September 1889, spotting the composer Charles Gounod dining in one of the Eiffel Tower restaurants, invited him up to his high-altitude office to join him and some other guests for coffee. It was a moment of reconciliation because Gounod had been one of the loudest voices against the construction of the tower.

I have taken a fair amount of the information here from the official Eiffel Tower website, including photos. It is well worth scrolling through:

https://www.toureiffel.paris/en

www.caroldrinkwater.com

My latest novel is THE HOUSE ON THE EDGE OF THE CLIFF

l

Tuesday, 25 June 2019

Emanuel Swedenborg and William Blake by Miranda Miller

For years I’ve passed Swedenborg House in central London but haven’t dared to go in. The reason for my curiosity is because ever since adolescence I’ve loved the paintings, illustrated books and poetry of William Blake, who was influenced by Swedenborg’s ideas.

So I was very pleased to be invited to a book launch in the Magic Lantern Room there by my friend Sally Kindberg a few weeks ago. Swedenborgianism bases its teachings on the writings of Emanuel Swedenborg, who was born in Stockholm 1688. He was a polymath who had a brilliant career as a theologian , scientist, inventor, philosopher and mystic.

Here’s a drawing from his notebook (in 1714) of a flying machine. The pilot was supposed to sit in the middle and use paddles on the wing, like oars on a boat, to propel himself through the air. Swedenborg commented, “ The art of flying is hardly yet born. It will be perfected and some day people will fly up to the moon.” He studied anatomy and physiology and anticipated the neutron concept. He also believed that slavery should be abolished, observing that the inhabitants of the interior of Africa had preserved a direct intuition of God. As a result the first abolitionist society was founded by Swedenborgians in Sweden in 1779.

When he was in his late fifties and living in London he had a vision of Christ, who told him that he had been chosen to interpret the Scriptures and reform Christianity; he was to be given freedom to roam in the spirit world. He spent the remaining 28 years of his life writing about his adventures there and his conversations with angels, demons and spirits from, amongst other places, Jupiter, Mars, Mercury, Saturn, Venus and the Moon. His best known books are Heaven and Hell and The Heavenly Doctrine, in which he claims that the teachings of the Second Coming of Jesus Christ have been revealed to him. Swedenborg has been described, intriguingly, as a “secret agent on earth and in heaven.” Swedenborg called his movement The New Jerusalem Church but it only became an institution after his death. Blake commented, “It is so with Swedenborg; he shews the folly of churches & exposes hypocrites”

Swedenborg died in London in 1772 – apparently on the precise day he had predicted. He had, and still has, many followers. It has been suggested that his ideas influenced Joseph Smith, the founder on Mormonism. Writers who were interested in his ideas include Conan Doyle, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry James, Immanuel Kant, Balzac, Helen Keller, August Strindberg, Edgar Allan Poe, Walt Whitman and W. B. Yeats. Jorge Luis Borges called him “the most extraordinary man in recorded history.“ His unorthodox beliefs were a magnet for dissentors and intellectuals interested in radical politics which, in the late eighteenth century, were often linked to mysticism.

William Blake is seen here in a portrait by Thomas Philips. In the bookshop on the ground floor of Swedenborg House books by and about Blake are prominently displayed. Alexander Gilchrist, Blake’s first biographer, wrote that “of all modern men, the engraver’s apprentice was to grow up likest to Emanuel Swedenborg.” Some scholars think that Blake came from a family of Swedenborgians and the Irish poet William Allingham imagined the fourteen-year-old Blake meeting the eighty-four-year-old Swedenborg on the streets of London.

We know that Blake owned and annotated at least three of Swedenborg’s books and he mentions two others in such a way as to suggest that he read them. He and his wife Catherine attended the first General Conference of the New Jerusalem Church in 1789. Blake would have sympathised with the Conference’s endorsement of Swedenborg’s statement that the things seen by the visionary “are not fictions but were really seen and heard in a state in which I was broad awake.” Like Blake, Swedenborgians had to defend themselves against charges of “enthusiasm” and madness. The Church that Blake visited was a development of the non-orthodox Theosophical Society which was established in 1783 by a printer with a Methodist background, Robert Hindmarsh. We know that a number of Blake’s friends and fellow artists were Swedenborgians and met in the Theosophical Society (in 1785 renamed as The British Society for the Propagation of the Doctrines of the New Church).

In Blake’s epic poem Jerusalem he speaks of a “Jerusalem in every individual man, ” a very Swedenborgian idea. Both men had unconventional ideas about marriage and sexuality. In Visions of the Daughters of Albion Blake describes sexual violence, linking sexual liberation with human freedom. Oothoon rages at her lover Theotormon for his “hypocrite modesty.” She describes herself as “A virgin fill’d with virgin fancies”; in accordance with the ideal of the virtuous woman at the time, she is not allowed to express her true sexual desires. In a paradise on the coast of Africa similar to the one described by Swedenborg in his Plan, Oothoon describes a utopian future time of free love, when “Love! Love! Love! happy happy Love!” can be “Free as the mountain wind”

Many Swedenborgians shared another of Blake’s deepest concerns: opposition to slavery. In his long poem America Blake’s revolutionary spirit, Orc, is referred to as “the Image of God who dwells in the darkness of Africa.

Later Blake seems to have turnied sharply against the Swedenborgians and satirized them in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790-93). “How do you know but ev’ry Bird that cuts the airy way, Is an immense world of delight, clos’d by your senses five?” Blake began to mistrust the church's emphasis on the avoidance of sin and eventually accused Swedenborg of “Lies and priestcraft” while the New Jerusalem Church split into factions. Swedenborg's greatest error, according to Blake, lay in his failure to understand the real nature of evil.

Blake saw Heaven and Hell not as real locations but as representations of the human heart. For him, angels represented conservative values whereas devils were rebels; Blake saw himself as a revolutionary devil and also used the concepts of Heaven and Hell in his own polemic against the materialistic philosophies of Locke, Bacon and Newton.

Blake’s private mythology, which make many of his beautiful poems hard to follow, was certainly influenced by Swedenburg’s writings and I find this a helpful approach.

Monday, 24 June 2019

AN INTERESTING FIND IN CHEPSTOW By Elizabeth Chadwick.

|

| Chepstow Castle from my hotel window. |

Since it was an evening talk and I live three hours' away by train, I stayed overnight. The organisers arranged for me to stay in The Woodfield Arms Hotel (formerly The Castle View) directly facing Chepstow Castle.

Arriving in my room which had all the facilities of an en suite a lovely comfortable bed, and indeed a view of the castle, I noticed a large, closed, dark-red striped curtain half way up the wall at the side of the bed, and underneath it, a photo frame with some information. My photo is too small for the information to be read clearly, but it's about Piercefield House a Neo-Classical country house, now a ruin. Here's the Wikipedia article. Piercefield House Why the information is there in the photo frame is because the curtains hide from the light, a fading but magnificent wall mural of Piercefield House painted in its Queen Anne heyday, and there for guests staying in this room to view.

|

| information plaque . Behind the red curtains = Piercefield House mural . R |

Sunday, 23 June 2019

A Victorian Scandal: The Peer and the Dancer by Judith Allnatt

In 1851, the Spanish dancer Josefa Duran, known as ‘Pepita’ caught the eye of Lionel Sackville-West, a member of the British aristocracy (2nd Baron Sackville). She was slim and beautiful and was known for the airiness of her dancing, for her luxuriant, waist-length dark hair and for the kiss curls she wore on each cheek. She had what we would now call ‘celebrity status’ and young men were said to have plucked flowers from their own wives’ hair to cast them at her feet on the stage.

Born in a Málaga slum to a barber father and a clothes-seller mother, Pepita’s background couldn’t be further from that of Lionel’s family, who owned Knole, one of the largest and most important of Britain’s Great Country Houses. They met a week or so after Lionel had seen her at the theatre; Lionel visited and they soon became ‘intimate’. A further obstacle to the lovers, beyond the chasm between their social classes, was that Pepita had in fact married another dancer, Juan Antonio de Oliva, only the previous year. They had separated swiftly in circumstances that Oliva maintained were ‘not honourable’ to Pepita and she had left Spain to tour abroad.

|

| The Cartoon Gallery, Knole |

Their relationship was intermittent in nature. As first attaché in Berlin, Lionel was able to visit Pepita in the cities and towns in which she was dancing but there were inevitably spells when they were apart. Pepita was certainly no angel; she appears to have had other liaisons with Prince Youssoupoff in Munich and Duke Maximilian Joseph in Bavaria. After Lionel and Pepita’s daughter Victoria was born, they separated for two years but Lionel returned to her after hearing that she was desperately ill. She had lost a baby and refused to say who the father was, but nonetheless they were reconciled.

In 1866, having given up dancing, Pepita had luxurious clothes, beautiful jewels and a house bought for her by Lionel in the French coastal town of Arcachon. Nonetheless, she was isolated by her situation. Unaccepted by society because she and Lionel were not married, she was unable to mix socially in Lionel’s circle. When they stayed in Paris, Pepita was reduced to tears because she was unable to go with Lionel to a fete in the Tuileries that he was visiting. His colleagues at the Foreign Office knew nothing of his liaison or the fact that he had children. He had never mentioned that part of his life. Now at Arcachon, her children were short of playmates as the children in the neighbouring villa had been told by their parents not to play with them. When entertaining, it was reported that no ‘ladies’ ever attended, that her guests were young men and that she drank.

In 1866, having given up dancing, Pepita had luxurious clothes, beautiful jewels and a house bought for her by Lionel in the French coastal town of Arcachon. Nonetheless, she was isolated by her situation. Unaccepted by society because she and Lionel were not married, she was unable to mix socially in Lionel’s circle. When they stayed in Paris, Pepita was reduced to tears because she was unable to go with Lionel to a fete in the Tuileries that he was visiting. His colleagues at the Foreign Office knew nothing of his liaison or the fact that he had children. He had never mentioned that part of his life. Now at Arcachon, her children were short of playmates as the children in the neighbouring villa had been told by their parents not to play with them. When entertaining, it was reported that no ‘ladies’ ever attended, that her guests were young men and that she drank.

At Arcachon, the house was named ‘Villa Pepa’: a name that may show Pepita’s egocentricity or may reflect a sense of defiance at her exclusion and the desire to make a world separate from the stresses of the ‘society’ around her. The desire to create another ‘world’, is perhaps echoed later in the haven from the public sphere made by her grand daughter Vita Sackville-West and her husband, Sir Harold Nicolson, in their gardens at Sissinghurst.

What was the truth about Lionel and Pepita’s relationship? Were they ever married? It became important decades later because of question over who should inherit Knole. For years Lionel was steadfast in putting up objections to signing the register of his children’s births. Later, when pressed to do so by Pepita for the sake of her reputation, he signed for two of his children but later claimed that he had no memory of doing so. One of these was Pepita’s youngest living child – Henry – who was later to feel therefore that he had a claim to be Lionel’s true heir.

In Arcachon society there was gossip that her children had several different fathers including the Prince of Bavaria and Count Henri de Béon, alongside Lionel. One can see how these rumours might arise as Pepita appointed Henri de Béon as her superintendant at the villa and gave him a bedroom next to hers. Lionel seemed to know about Béon living there but didn’t send him packing. Whether this was because he held no suspicions or because he was extremely tolerant of his mistress’s amours is not clear.

At forty, Pepita gave birth to another son, Frederic, but both mother and baby survived only a few days. According to Vita’s account in her book ‘Pepita’, Lionel broke down at seeing Pepita and the baby laid out together. He blamed himself for her death, sobbing that he had killed her, presumably because he had fathered the child when Pepita was an older mother. As if fuelled by guilt, from that point on Lionel seemed to refer freely and publicly to Pepita as his wife; she is named as such in the funeral invitations, letters and in the notices in the local paper. Ironically, only in death did Pepita receive the acknowledgement of their relationship that she had craved through their many years together. She was buried, as Lionel’s wife, in the municipal cemetery above the town. Béon and his mother took care of the five children, supported financially by Lionel, who referred to him at the time as a ‘dear friend’.

The consequences of Lionel and Pepita’s unconventional liaison rumbled on decades after Pepita’s death. Lionel’s nephew (confusingly another Lionel) had inherited Knole in the absence of a ‘legitimate’ son. Henry brought a case that sought to prove that Pepita had been secretly married to Lionel, that he, Henry, had been registered as Lionel’s child and that he was therefore the male heir. The scandal caught the public imagination to the extent that a drama was shown, catchily named ‘The Marriages of Mayfair’ that was a thinly veiled reference to the Sackville-West affair. For Henry and the court case however, it was impossible to cast doubt on the legality of Pepita’s marriage to De Oliva, that had in fact continued throughout Pepita and Lionel’s affair. Henry lost the case and Knole continued in the hands of the accepted line of Sackville-Wests.

'Vita - the Life of Vita Sackville -West' by Victoria Glendinning

Labels:

#HISTORY,

#Victorian,

19th century,

Judith Allnatt,

Knole,

Sissinghurst,

Victorian,

Vita Sackville-West

Saturday, 22 June 2019

Wedding Lintels & Marriage Customs by Catherine Hokin

|

| Marriage Lintel from 1610, Falkland |

A marriage lintel (also known as nuptial, marriage or lintel stone) is a carved inscription above the doorway of a house owned by a newly-married couple. They are a feature of the east coast of Scotland and date primarily from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries - the one pictured from 1610 is one of the best examples and commemorates the marriage of Nicol Moncrief, a servant of James VI. All feature the year of the wedding and the couple's initials and some also include pictorial details - there is a particularly lovely one on what is now known as the John Knox House on the Royal Mile in Edinburgh, commemorating the marriage of goldsmith John Mossman to Mariotta Arries.

|

| Stone from 1801 |

The lintels serve as a record of a marriage and the joining together of two families, who were often aristocratic or monied. Lintels could be added to a building which was built specifically for the married couple, or were carved into a pre-existing lintel. They were always set over the main entrance and some also appear inside houses, above the most visible fireplace. Wherever they were placed, they were meant to be seen: perhaps we should think of them as an early form of social media - Mr and Mrs Smug-Married boasting about their updated status and their swanky new home.

There is, unfortunately, little information about the lintel stones beyond what they symbolise - or little I can find. There's no list of the surviving stones (although Wikipedia cites some examples if you want to go hunting) and, as you can see in the third photo, many have become detached from their original position.

The custom of marriage lintels had died out by the end of the nineteenth century, as have some of the other traditional Scottish practices. Grooms are no longer expected to carry a creel (a large basket) filled with stones around the village until their bride releases them from their burden with a kiss. Brides might still find themselves standing to the groom's left but hopefully no one is still doing it because the

bride is the ‘warrior’s prize’ who the groom needs to hold with his left hand so he can fend off her family and other foes with his right. Similarly presenting swords from one family to the other as a sign of extended protection and acceptance isn't regarded as quite so crucial anymore.

|

| A quaich |

Some customs do, however, continue. Although grooms aren't necessarily required to bring 'siller' (silver coins) to the ceremony anymore, a traditional wedding will still involve a scramble - throwing coins in the air for the children to collect. Wedding walks still take place, where the wedding party walk to the church preceded by a fiddler. Whether they have to turn around and start again if they meet a pig or a funeral as the rules once dictated is presumably a matter of choice these days, or very bad luck. Many couples still use a quaich, a two-handled 'loving cup' for the first toast to symbolise the joining of their lives. This tradition stems, as many of these practices do, from clan customs: the quaich was once used by two clans to celebrate a bond between them, with each leader sharing the whisky it contained. In a similar vein to sharing the quaich, some couples will still 'pin the tartan' - swapping rosettes to show that both husband and wife are accepted by the other's families. For anyone wanting to delve further, there are some excellent oral histories here, including blackening, the breaking of the bride-cake and betrothal customs.

|

| The Goddess Juno |

Where Scots have broken with custom is the wedding date. Traditionally the most popular auspicious month to marry was June - this was partly because the goddess Juno (for whom June is named) was the protector of women, particularly in marriage and childbearing. On a more practical note, others chose June in order to time conception so that births wouldn’t interfere with harvest work. Last year, however, the most popular month in Scotland was September - no doubt because this is the one month of the year when the weather is at its most predictable. A Scottish June bride needs a dress that co-ordinates with wellies, an umbrella and, this year at least, a winter coat!

If you and yours are struggling to choose the right month for an upcoming ceremony, perhaps this poem might help. The message about May does seem rather clear...

Married when the year is new, he’ll be loving, kind and true.

When February birds do mate, you wed not dread your fate.

If you wed when March winds blow, joy and sorrow both you’ll know.

Marry in April when you can, joy for Maiden and for Man.

Marry in the month of May, and you’ll surely rue the day.

Marry when June roses grow, over land and sea you’ll go.

Those who in July do wed, must labour for their daily bread.

Whoever wed in August be, many a change is sure to see.

Marry in September’s shrine, your living will be rich and fine.

If in October you do marry, love will come but riches tarry.

If you wed in bleak November, only joys will come, remember.

When December snows fall fast, marry and true love will last.

–Anonymous

Which ever you go with, have the happiest day and, in the words of this Scottish blessing: May your blessings outnumber the thistles that grow and may troubles avoid you wherever you go. Now let's see if you can still recite that when the bills come in...

Labels:

Catherine Hokin,

Juno,

marriage,

marriage customs,

Scotland,

wedding lintels,

weddings

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)