"France is Josephine."

1906-1975

This is one of the photos I took of the facade of the Panthéon, snapped while I was queuing to pay my respects to Josephine Baker. Exceptionally, during that first weekend of December, entrance was free to everyone, thus offering citizens the opportunity to say farewell to a woman who had come to France as a teenager escaping racism and segregation, and made this country, where she found acceptance and success, her home.

Whilst I was in Paris a few weeks ago, on a cold winter Saturday afternoon, I took myself off to the Panthéon. There I queued in the Place de Panthéon along with hundreds of others waiting to enter the Tomb of Heroes. Fortunately for us all, the rain and biting wind stayed away for those few hours we were in line. Everyone was in good spirits. A few days earlier on Tuesday 30th November 2021, Josephine Baker had become the first Black woman to be inducted into France's Tomb of Heroes. President Macron hailed the American-born dancer, singer, night-club artist and courageous French resistance fighter as a 'symbol of unity in a time of division'.

Baker was born Freda Josephine McDonald in St Louis, Missouri in 1906. Her childhood was spent in poverty. Her mother, who was abandoned by Baker's father, Eddie Carson, a vaudeville drummer, soon after their daughter's birth, worked as a washerwoman. To help her mother keep the family fed Josephine from the age of eight went out to clean and babysit. Most of the houses where she was employed were owned by rich white folk who didn't treat her well.

She was also profoundly marked by the race riots, the lynchings she witnessed when she was eleven. The East St. Louis 'Race War.' At least 39 black citizens were brutally killed, many of them lynched. This and the desperate times and discrimination she encountered during her childhood years, played an important role in her work later with Martin Luther King and the Civil Rights Movement.

Josephine quit school at 12, lived on the streets, scavenged for food, eventually running away from St Louis when she was thirteen. At thirteen she married and separated weeks later. Finally, at sixteen, after stints of waitressing, she found herself touring the United States with the Jones Family band and the Dixie Steppers. She had been teaching herself to dance and to turn her hand to a few comedy routines.

In 1921, she married for the second time, one Willie Baker, a railway worker. The marriage did not last but she kept his name for the rest of her life. By now she was in New York performing in Chocolate Dandies and, along with the renowned singer-actress Ethel Waters, Josephine was in the floor show at the Plantation Club. It took no time before she became a big hit with the audiences. By 1925, nineteen-year-old Josephine decided to take her chances in Europe, in Paris where Les Années Folles - France's equivalent of the Roaring Twenties - were in full swing. Paris was jumping to the beat of the jazz. Baker sailed to France, landed in Cherbourg and opened on 2 October in La Revue Nègre at the Théâtre des Champ-Élysées. For her role in this she was paid 250 dollars a week which was double her Broadway salary. Nineteen years old, she was a sensation. Paris brought her stardom; it also showed her that there was another way to live. There was dignity. She became a protégée and friend of Ada "Bricktop" Smith, another extraordinary black American vaudeville star who was taking the French capital by storm, making it her home.

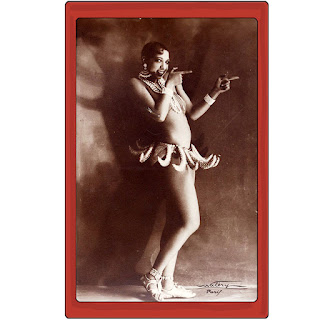

Paris in the twenties was an exceptional city to be living in. Cole Porter, E.E. Cummings, John Steinbeck, Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Picasso, to name but a few, all were present. Josephine was not only very much a part of that multi-cultural scene, she was admired, fêted. She wowed spectators when performing at the Folies Bergère wearing a skirt, a tutu, made of 16 bananas. It drew attention, while her Charleston dancing drove the audiences wild. ("I am not naked, I am just not wearing any clothes.") By the time she was twenty-two Baker was one of the highest paid performers in Europe.

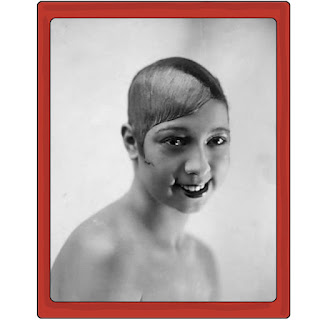

Photo taken in 1920s.

She was the first Black woman to star in a motion picture, Siren of the Tropics, in 1927. A French film directed by Mario Nalpas and Henri Étievant. (A little known fact I discovered when I was researching for this post: Luis Bunuel worked as assistant director on this film). It was a motion picture well ahead of its time and ran for six months in French cinemas which was considered a great success. Baker was during these years of the twenties the leading star of the Folies Bergères cabarets. Her on-screen presence was hailed as magnetic. She was in every sense a star, and a groundbreaking one at that.

She toured Europe, studied French, and built herself a remarkable reputation.

Josephine in her banana skirt.

In 1936, she returned to the States to star in the Broadway show, Ziegfeld Follies, hoping to replicate her European success, but she had not counted on the level of discrimination that would greet her. Time magazine mocked her, calling her a "buck-toothed Negro" whose talent could be matched by anyone. Broken-hearted, less than a year later, she returned to France resolving to make it her permanent home. Upon her return she married for the third time, a French industrialist, Jean Lion (born Levy). This offered her the opportunity to take citizenship, which she did.

It was also around this time, before the outbreak of WWII, that Baker bought a renaissance castle overlooking the Dordogne River in south-west France, Château des Milandes. This home became a place of great significance. She organised for her family tp be brought over from St Louis and gave them a home there. She and her husband lived there until he - being of Jewish origin - was obliged to flee the Nazis.

When France declared war on Nazi Germany in September 1939, Josephine immediately stepped up to participate in the war effort .She joined the counter-intelligence service, using her charms and reputation to gather information. She worked in cafes, clubs, bars and embassies. She also helped raise funds for the French army, as well as paying for her family to return to safety back in the United States.

When France capitulated in the early summer of 1940, Baker turned her talents to gathering information for the Résistance. She passed on coded information through her musical scores. She moved to Morocco to entertain the Free French and Allied troops. After the war, having returned from North Africa and the Middle East as a second lieutenant in the French air force, she was awarded both the Croix de Guerre and Legion of Honour with the rosette of the Résistance. France's highest civilian and military distinctions.

After the war, Baker married for the fourth time, the bandleader Jo Bouillon. She spent most of her time at Château des Milandes. In 1947 she began to adopt children - a hysterectomy earlier in life meant that she couldn't bear children of her own. The "Rainbow Tribe" is the collective name she gave to her offspring. Twelve adopted infants from all over the world. She saw her family as an experiment in brotherhood and frequently invited people to the estate to see how happily they all lived together.

In the 50s, Baker returned to the States to take on another cause, one to which she was as deeply committed as she had been to the freeing of France: the Civil Rights Movement. She has been famously quoted as saying that she could walk into palaces, embassies, the residences of some of the rich and famous, but back home in St Louis she couldn't walk into a bar and order a cup of coffee. She fought against segregation and refused to perform in any club or venue where segregation was in force. She marched with Martin Luther King, spoke out against the poverty and indignities suffered by the African-Americans. She was eventually accepted by America as an artist and a voice in her own right. 20th May was named Josephine Baker Day.

In 1975 back in Paris, fifty years after her first performance in the country that had welcomed her and given her dignity, she performed at the Theatre Bobino. It was to have been the opening of a series of concerts. Amongst many luminaries in the audience that night was Diana Ross, Mick Jagger, Sophie Lauren as well as Baker's very dear and loyal friend, Grace Kelly, Princess Grace of Monaco, who had given Josephine a sea-view residence in Roquebrune close to Monaco after Baker lost her chateau in March 1969, because she could not meet the bills and running costs. Tragically, there were only three performances at Bobino because Baker suffered a cerebral haemorrhage in her sleep. She was taken in a coma to the Pitié-Sapêtrière Hospital in Paris where she died two days later.

Crowds lined the streets of Paris on the day of her funeral. She was given a twenty-one gun salute. The first American woman to receive full French military honours. She was later buried in a cemetery in Monaco, which is where her body remains today.

Her family requested that her body was not exhumed and moved to the Panthéon. In the coffin that was laid in the Tomb of Heroes on 30th November this year is earth from the soils of St Louis, Paris, Château des Milandes and, her final home, Monaco.

I walked the echoing stone floors of the former church of Sainte Geneviève and descended to the vast, impressively vast, crypt, at the Panthéon. I walked alongside, brushed spiritual shoulders with, such giants as Dumas, Malraux, Jean Moulin, Emile Zola, Victor Hugo. Voltaire, Rousseau.

But where were the women?

Only six women have been laid to rest in this sanctified place in their own merit.

Sophie Berthelot in 1907. Her husband was a famous chemist and the family were insistent that the couple be buried together. Polish-French physicist and Nobel laureate, Marie Curie, became in 1995 the first woman in her own right to be buried here. (Her husband Pierre, is also honoured with a place for his pioneering work on radioactivity.) Résistance fighters Genevieve de Gaulle-Anthonioz and Germaine Tillion were both inducted in 2015, Simone Veil in 2018 - Veil was also chosen by Macron - and lastly in 2021, Josephine.

Here lies Josephine:

Josephine Baker's place at the Pantheon.

Outside on the facade of the towering edifice is written: Aux grands hommes, la patrie reconnaissante.

'To the great men, the nation (fatherland) is grateful.' It always fascinates and rather amuses me that the word la patrie is feminine. There is certainly a move here in France to honour the women of the nation and Macron has contributed one third of those females now laid to rest in honour at the Panthéon. Personally, I would like to see the stone outside recarved to read: Aux grands femmes et hommes ...

You will have to look carefully to see the gold-lettered writing above the entrance pillars.

Are there any women whose names you would put forward to join Josephine Baker and the handful of other exceptional women now at rest in the Panthéon? I would be fascinated to hear them.