In 1947 the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to the British and American Quakers for their "compassionate effort to relieve human suffering," which included their work during the Spanish Civil War. It was given for their "silent help from the nameless to the nameless."

|

| Quaker Fundraising © Britain Yearly Meeting |

But of course the volunteers were not nameless, and a small handful of extraordinary women laid the groundwork for the large and well organised charitable responses we see today.

By 1936 Edith Pye was president of the British Midwives Institute and also an experienced humanitarian worker. She had qualified as a midwife in 1906 and become a member of the pacifist Society of Friends (Quakers) in 1908. During the First World War she set up a maternity hospital in France, inside the war zone, and was one of very few women to be awarded the French Legion d'Honneur.

When the Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936, refugees began to trek north, escaping the advance of Franco's fascist army and the worst fighting. Edith went to Barcelona to assess the needs of the children. Her report said,"food supplies are diminishing rapidly" and identified serious shortages of "milk, sugar, farinaceous foods and cod-liver oil." Fundraising by the Society of Friends and Save the Children International followed. Soon dried milk, plus donations of cocoa, biscuits and oats from Quaker companies, began to be shipped to Spain.

|

| Map 1937 © DKB Creative |

As the war continued, Edith Pye was instrumental in setting up a fund for Spanish refugee children. She persuaded the British Foreign Office to pledge £10,000 if other governments would do the same. Her efforts succeeded so well that by 1938 the International Commission for the Assistance of Child Refugees was based in Geneva and had money coming in from 24 governments. On the ground in war-torn Spain a team of British Quakers was put in charge of administering the distribution of thousands of tons of wheat and condensed milk and other goods which arrived in Barcelona. Two of the team were Francesca Wilson and Kanty Cooper.

Francesca, aged 49, was also a veteran of aid work. She'd studied history at Newnham College and became a teacher at Gravesend in Kent. At the start of the first world war she heard that Quaker Relief was helping civilians in France. She was interviewed by Ruth Fry at Friends House and stressed her fluent French and willingness to do any kind of work. But Ruth Fry turned her down, saying "You are engaged in useful work here. What is your motive for wanting to leave it? Is it a genuine concern for the relief of the unfortunate, or only love of excitement?" Despite this rejection, Francesca found a way to get to a POW camp on the Dutch island of Urk and from there to a refugee camp in Gouda, and later to work with refugees in France, Corsica, North Africa, Serbia, Austria and Russia.

|

| Francesca Wilson © Britain Yearly Meeting |

In 1937 the headmistress of her school gave her two months leave to go to Spain. She travelled south from Barcelona to Murcia, finding refugees suffering, "The greatest misery I've ever seen in my life." She swung into action, organising deliveries of food and serving breakfasts to the children and expectant and nursing mothers in the worst refugee night shelter, which housed 4,000 people who had escaped from Malaga. She saw children were dying – there was a 50% infant mortality rate – and called on Sir George Young, who agreed to fund a children's hospital, which Francesca got equipped and running in just over a week.

On subsequent leave from her teaching, she set up a farm school to give teenage boys an occupation and stop them joining the army, and a holiday camp which became a full time "colony school" on the beach near Benidorm, to give refugee children a healthy break in the fresh air. She strode fearlessly into war zones and appalling situations, saying, "I have a species of arrogance that this is not my time to die... My insolent confidence protects me from fear."

|

Spanish civil war map 1938 © DKB Creative |

For the Spanish-speaking English sculptor Kanty Cooper, who had studied under Henry Moore, the war was her first taste of relief work. Her "indignation at the injustice of our non-intervention policy which crippled a socialist, democratically elected government fighting a right wing fascist revolt," led her to help out with the 4,000 Basque children who had been evacuated to Britain. Then she developed neuritis. "It was like arrows of fire down my arms at night." Her doctor told her she would have to stop sculpting for at least six months, so she decided to go to Spain.

|

| Kanty Cooper © Len Lye Centre NZ |

In January 1938 she arrived in Barcelona and was immediately put in charge of three of the canteens being managed by the British Quakers. One of these alone fed 3,000 children a day. Thousands of refugees continued to pour into Barcelona and the city was under constant air attack from Franco's forces. After a "short apprenticeship" Kanty took over the running of all the Barcelona canteens and opened more until every district had its own. By September 1938 she was running 74 canteens feeding 15,164 children and by January 1939, 132 canteens served 27,532 every day. There were perhaps a million refugees in Catalonia, of whom many passed through Barcelona on their way north towards France. As Franco's forces closed in on the city, most of the foreign aid-workers left, but Kanty stayed in Spain for a further five weeks, distributing the last of the food stores.

|

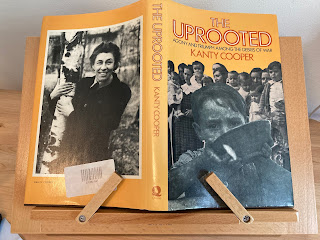

| Kanty Cooper's memoir The Uprooted. Author's photograph. |

After the Spanish Civil War, these three women continued their life-saving humanitarian efforts. Francesca went on to support refugees in France and Hungary, while Kanty worked in Greece, Germany, Jordan and Amman. Both Kanty and Francesca wrote moving memoirs. During WW2 Edith Pye became a leading member of the Famine Relief Committee and worked in both France and Greece. She was awarded an OBE.

Francesca Wilson and Kanty Cooper both appear in Maggie Brookes' new novel Acts of Love and War published in June 2022 in the UK and August 2022 in North America.

2 comments:

Incredibly brave women.

This is fascinating, Maggie.Thank you. My novel set during WWII and published last year by Penguin is titled 'An Act of Love'. A similar title. Mine, though inspired by a real situation in the Alps in France in 1942 -1943 is a fictitious story. Again, based on, inspired by extraordinarily brave women. I am humbled when I read such accounts of women who not only contributed so much to assist refugees but fought hard to be allowed to do so.

Post a Comment