|

| Wilfred Owen 1893 - 1918 |

If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,—

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

Dulce et Decorum Est - Wilfred Owen

..Tonight, this frost will fasten on this mud and us,

SShrivelling many hands, and puckering foreheads crisp.

The burying-party, picks and shovels in shaking grasp,

Pause over half-known faces. All their eyes are ice,

Exposure - Wilfred Owen

Wilfred Owen died 104 years ago today, a week before Armistice was declared and the war was over. There is something especially poignant being killed so close to the ending of hostilities. My Uncle Bob was killed on 14th June, 1918, close enough for the family legend to grow that he was killed in the last days. My uncle’s experience is largely unknown and unknowable. He sent letters to his family, pencil written because he was ‘other ranks’. He also sent water colour sketches of the places, churches and castles he saw behind the lines. He pressed wildflowers he found growing in no-man’s-land, on the borders of the roads he tramped, in the trenches he manned. Poppies, yes, but also Larkspur, Scabious, Ragged Robin. He saw beauty there, as Owen did. We know nothing of his other experiences: the suffering he saw, the fear, the fighting and dying. In that Wilfred Owen speaks for him. He speaks for all of them.

|

| My Uncle Bob with his family |

|

| His temporary grave in Flanders |

|

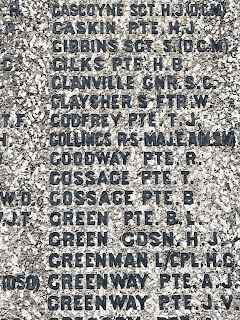

| His name, Pte R. W. Goodway, on the War Memorial in Leamington Spa |

2 comments:

Wonderful, Celia. Thank you. I didn't know 'Exposure' and what a poem! I'm surprised it isn't as well known as 'Dulce est Decorum...'

On my Grandmother's wall hung a framed, sepia photograph of a handsome young man in uniform. Its frame was completely covered by poppies, some bright and new, some faded. He was, I was told, her youngest and favourite brother, William, killed in World War I.

We're probably the last generation to have that almost personal contact with 'those who died like cattle.' In that war, at least.

Thank you, Celia for a post that so fits this time of year, and for reminding us of "other ranks", who rarely spoke about their experiences yet saw the same flowers and fields and casualties.

I was haunted by Owen's powerful words when the teachers introduced his lines to us at my school, and as you describe, that younger generation were more than ready to receive their message.

I often remember the influential trio of unmarried teachers who taught English, History and Latin in my grammar school convent, They entered the classrooms with their degree gowns floating behind the but they and their families had experienced the effects of those two wars. How on earth did they feel while teaching these poems to the girls before them?

Post a Comment