|

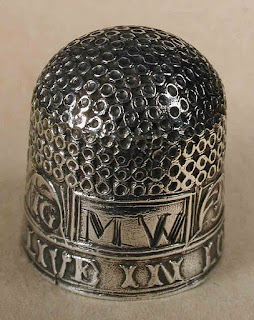

| 17th Century silver thimble Photo: Llangefni |

In my Jacobean novel Traitor in the Ice, one of my characters passes a secret note to another folded into a band and hidden inside a thimble. This method of passing secret or coded messages was frequently used in times of religious persecution during the Tudor period and probably for centuries before that, and was still being used during the 17th century English Civil War. A band of folded paper was easily concealed in a thimble, which, even in a room crowded with people, a woman could causally set on table for the recipient to pick up, or it could be slipped into a work basket. Even the decoration on the thimble itself could be used as a coded message.

But the practising of concealing things in thimbles has a much older origin and is linked to what the thimble has come to symbolise.

Thimbles have been excavated from ancient Chinese sites dating as far back as the 206BC to 220CE, as well as from Roman sites, such as Herculaneum and Pompeii, buried when Vesuvius erupted in 79CE.

%20cropped.jpg) |

| Copper-alloy thimble ring c. 1400-1600 Found in East Sussex Photo: Andy Stanley The Portable Antiques Scheme/ The Trustees of the British Museum |

In the Middle Ages, most thimbles made from brass or copper alloy and were used by men, women and children. For sewing coarse cloth, they used topless thimble rings, pressing the needle with the side of the finger, and for finer cloth and embroidery, they used bee-hive shaped thimbles.

By Tudor times, the giving of elaborately decorated thimbles as a lover’s token or an occasion gift was well established. These were often engraved with initials, coats of arms, and mottos, or decorated with emblems in the forms of birds, flowers and animals. Queen Elizabeth bestowed thimbles studded with precious stones on her favoured ladies-in-waiting.

%20cropped.jpg) |

| C. 1708, a child's silver thimble with machine made circular punch marks Photo: Kult Adams, Bristol City Museum The Portable Antiques Scheme/ The Trustees of the British Museum |

But thimbles had become far more than tools for sewing, they had taken on symbolic meanings too. Traditionally, a ring, a coin and a thimble are baked into a wedding cake for guests to share. The person who gets a ring will find happiness. The one who gets the coin will become wealthy, but the one who gets the thimble with remain unwed, a ‘spinster.’ The same applied, if a girl was gifted three thimbles, presumably because that meant she’d had three suitors and had not settled for any of them.

|

| 'First Sun' by Camille Martin (1861-1898) Photo: Vassil Museum of Fine Arts of Nancy |

The more important meaning of thimble, though, was protection and good fortune. A thimble is one of the most common objects metal detectorists unearth in fields and gardens. Many were simply lost there. At harvest time, field hands often wore thimbles to protect their hands when binding straw, and women and children would join menfolk for the harvest, and continued to sew or mend while resting from the heat of the day. So many thimbles were probably mislaid. But some seemed to have been deliberately placed in the earth, and contain scrolls of paper, grains of cereals, hazelnuts, crystals, and pebbles, many found with scraps of cloth inside. Some of these clothes, of course, would have been rags used as padding to keep the thimble snug to the finger, but not all.

Since thimbles symbolised protection, if a woman was anxious about a son going off to war, a daughter giving birth, or a lover on a sea voyage, she’d write their name on a piece of paper and tuck it into a thimble, which she’d then bury in the earth to protect them. If she couldn’t write, she’d use some scrap belonging to the person, such as a strip cut from a garment or a fragment of something they'd used, even a piece of a consecrated wafer from Mass.

%20cropped.jpg) |

| Copper- alloy thimble c.1400-1600 Found on the Isle of Wight Photo: Frank Basford, Isle of White Council The Portable Antiques Scheme/ The Trustees of the British Museum |

The thimble could also be used to protect the whole household from the plague, or as a prayer for a good harvest. So, while thimbles unearthed with a grain of wheat or corn in them can simply be the result of them being lost during harvesting, sometimes a grain of corn might have been put inside deliberately.

Often too something red would be added – a red bead, rowan berry or red thread to keep what was inside safe, and ensure it couldn’t be taken by evil spirits to cause harm. In a curious blending of the two superstitions, some years ago, I was thrilled to be given two Victorian silver thimbles by an elderly lady, which were tied together by a red cord. But I was warned never to cut or untie the red cord or tie a third thimble to the cord, for fear of bad luck.

Right up until the 1940’s, the tradition was that if a wife of a famer or farmworker died, a strip of cloth cut from her dress would be stuffed into her thimble and thrown out on to the field where she had worked. If a corpse of a woman was proving difficult to get inside a coffin because of stiffness or size, it was said that if her thimble was cast into the coffin first, her body would follow easily.

|

| A Nürnberg thimble Cast brass 14th Century Photo: Llangefni |

So if you are lucky enough to dig up an old thimble in your garden, do check carefully inside it before you wash the mud out.

If want to discover more, a good starting point is thimbles (colchestertreasurehunting.co.uk). It has a fascinating piece on the history of European thimbles, including why ‘Empress Maria Theresa of Austria. sent spies to Nürnberg to steal the secret of the thimble making,’ together with some excellent photographs of thimbles found in fields and gardens, dating from 12th century onwards to help you date yours.