It is almost impossible to pick the ‘best bits’, as each week we have read something that resonates, entertains, surprises or even comforts us. Therefore, I decided to flick through my well-worn copies of each of the books and to stop where I noticed the most scribbles in the margin, or perhaps highlighted sections of the text, and have chosen from those pages a selection of passages which I hope you will enjoy. If you are new to Homer, Virgil and Ovid, this may give you a flavour of the style and subject matter of these wonderful poets and, I hope, tempt you to read more.

All quotations are taken from the Penguin Classics series, the cover images of which I have included for each work. I have chosen this set of translations as they were the first versions of these poems which I read and have therefore been on my bookshelves for as long as I have been studying and teaching Classics. But the variations between translations and the difficulty of choosing just one for each Greek or Latin work was the topic of a History Girls’ blog I wrote last year.

As these passages are simply a taster, I have not attempted to summarise the stories of the epics or provide a detailed background. Some of the themes, such as the Trojan War, or characters from Greek mythology, such as the Cyclops, may be familiar in any event. However, for each one I have noted whether the original poem was Greek or Latin and the approximate date when the poem was composed and/or completed. The dates for Homer’s epics are approximate and the source of much academic debate.

Homer’s Iliad - Greek - around 750BC

Homer’s characters often utter observations which have a distinctly proverbial flavour, such as this musing by one of the warriors on the battlefield outside Troy:

Or this:

…whatever we do, the fates of death stand over us in a thousand forms, and no mortal can run from them or escape them… (Book 12: 326-7.)

Homer is also known for his vivid and striking similes. The Trojan prince, Paris, whose love affair with Helen was the cause of the Trojan war, is cleverly captured with this simile:

Paris did not dally long in his high house, but once he had put on his glorious armour of intricate bronze, he dashed through the city, sure of the speed of his legs. As when some stalled horse who has fed full at the manger breaks his halter and gallops thudding across the plain, eager for his usual bathe in the lovely flow of a river, and glorying as he runs. He holds his head high, and the mane streams back along his shoulders: sure of his own magnificence, his legs carry him lightly to the haunts where the mares are at pasture. So Paris, son of Priam, came down from the height of Pergamos, bright in his armour like the beaming sun, and laughing as he came, his quick legs carrying him on. (Book 6: 503-14.)

Similes are also used to heighten the pathos of a scene. Note here the reference to Menelaos, the Spartan king and husband of Helen, now in the thick of the Trojan war and trying to reclaim his wife from Paris:

As when a woman stains ivory with crimson dye, in Maionia or Caria, making a cheek-piece for horses. It lies there in her room, and many horsemen yearn to have it for the wearing: but it waits there to be a treasure for a king, both horse’s finery and rider’s glory. Such, Menelaos was the staining with blood of your sturdy thighs, and your legs, and your fine ankles below. (Book 4: 141-7.)

A simile is used to great effect to describe the leader of the Greeks, and brother of Menelaos, Agamemnon:

Agamemnon rose to speak, letting his tears fall like a spring of black water which trickles its dark stream down a sheer rock’s face. (Book 9: 13-15.)

Words, so important in Homer’s oral tradition, are often likened to nature:

But when he released that great voice from his chest and the words which flocked down like snowflakes in winter, no other mortal man could then rival Odysseus. (Book 3: 221-3.)

Nestor the sweet-spoken, … from his tongue the words flowed sweeter than honey. (Book 1: 247-9.)

Homer’s Odyssey - Greek - around 725BC

Odysseus returns home to Ithaca after twenty years of absence: 10 years at the Trojan war and 10 years making his tumultuous journey home. He is disguised but his faithful dog recognises him:

As they stood talking, a dog lying there lifted his head and pricked up his ears. Argus was his name. Patient Odysseus himself had owned and bred him, though he had sailed for holy Ilium [Troy] before he could reap the benefit… in his owner’s absence, he lay abandoned on the heaps of dung from the mules and cattle which lay in profusion at the gate…. But directly he became aware of Odysseus’ presence, he wagged his tail and dropped his ears, though he lacked the strength now to come nearer his master. Odysseus turned his eyes away, and, making sure Eumaeus did not notice, brushed away a tear….. As for Argus, the black hand of Death descended on him the moment he caught sight of Odysseus – after twenty years. (Book 17: 291-305… 326-7.)

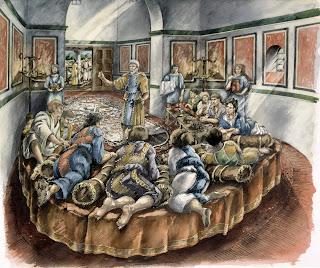

Odysseus is cunning, crafty and has a way with words. The word-play in the following episode is one of his more famous tricks. The Cyclops has just eaten alive some of Odysseus’ companions and washes them down with wine. Odysseus is narrating the story:

The Cyclops took the wine and drank it up. And the delicious drink gave him such exquisite pleasure that he asked me for another bowlful. “Give me more, please, and tell me your name, here and now – I would like to make you a gift that will please you. We Cyclopes have wine of our own made from the grapes that our rich soil and rains from Zeus produce. But this vintage of yours is a drop of the real nectar and ambrosia.”…

“Cyclops,” I said, “you ask me my name. I’ll tell it to you; and in return give me the gift you promised me. My name is Nobody.”…

The Cyclops answered me from his cruel heart. “Of all his company I will eat Nobody last, and the rest before him. That shall be your gift.” He had hardly spoken before he toppled over and fell face upwards on the floor, where he lay with his great neck twisted to one side, and all-compelling sleep overpowered him. In his drunken stupor he vomited, and a stream of wine mixed with morsels of men’s flesh poured from his throat. (Book 9: 353-9… 364-74.)

Odysseus and his men seize the opportunity and drive a sharpened olive stake, heated in fire, into the Cyclops’ single eye, blinding him. He shrieks and calls for help from his fellow Cyclopes who gather outside his cave and ask what is wrong and whether somebody is trying to kill him. The conversation that follows goes like this:

Odysseus’ trick has worked, just as the Trojan horse trick worked, another of Odysseus’ cunning plans, which brought an end to the ten year Trojan war. That story was not told by Homer but by our next poet, Virgil, in his epic poem, the Aeneid.

Virgil’s Aeneid - Latin - 19 BC

Rumour did not take long to go through the great cities of Libya. Of all the ills there are, Rumour is the swiftest. She thrives on movement and gathers strength as she goes. From small and timorous beginnings she soon lifts herself up into the air, her feet still on the ground and her head hidden in the clouds…. Rumour is quick of foot and swift on the wing, a huge and horrible monster, and under every feather on her body, strange to tell, there lies an eye that never sleeps, a mouth and tongue that are never silent and an ear always pricked. By night she flies between earth and sky, squawking through the darkness, and never lowers her eyelids in sweet sleep. By day she keeps watch perched on the tops of gables or on high towers and causes fear in great cities, holding fast to her lies and distortions as often as she tells the truth. (Book 4: 173-88.)

Book 4 is dedicated to the story of Dido and Aeneas. If you only have time to read one book of the Aeneid, this might be the one to pick. It inspired Purcell’s opera Dido and Aeneas which includes the haunting and exquisite Dido’s Lament. Virgil’s account hints at the tragic ending with this observation:

Love is a cruel master. There are no lengths to which it does not force the human heart. (Book 4: 412.)

Ovid’s Metamorphoses - Latin - AD 8

Perhaps what sets Ovid apart from Homer and Virgil is his wit and rather mischievous take on popular myths. He can certainly rival his predecessors in beautiful narrative and storytelling but this passage demonstrates his comic portrayal of the man-eating monster, the Cyclops, named Polyphemus, whom we met above. In Ovid’s version, Polyphemus has fallen in love with a beautiful nymph, Galatea, and attempts to win her affections:

The wild Polyphemus was combing his prickly locks with a mattock, attempting to trim his shaggy beard with a pruning-hook, and trying to look less fierce when he gazed at his face in a pool…. (Book 13: 765-7.)

“Truly, I know myself, I recently saw my reflection in pure clear water and liked the image that met my gaze…Don’t think me ugly because my body’s a bristling thicket of prickly hair….I’ve only one eye on my brow, in the middle, but that is as big as a fair-sized shield. Does it matter?” (Book 13: 840-1, 846, 851-2.)

Ovid invites sympathy for Polyphemus and shows his romantic side when Polyphemus attempts to woo Galatea with promises of gifts:

Sadly for Polyphemus his love is unrequited and, to add insult to injury, his beloved Galatea is smitten instead with ‘a beautiful boy of sixteen, with the first smooth down on his cheeks’ (753-4) – quite the opposite of a huge, hairy monster. Polyphemus’ romantic side soon turns to anger when he is rejected and he issues this threat about his love rival:

This sounds more like the Cyclops we met in Homer.

What next? Greek plays - 5th century BC

It is hard to follow the works of Homer, Virgil and Ovid but, inspired by our theatre trips to West End productions of Oedipus (two different ones within just a few months) and Elektra, Classics Club will spend the summer term reading Greek tragedies written by the playwrights, Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides. One of our members discovered this lovely edition with 16 plays in total: how will we choose which ones to read together? Perhaps we shall simply read them all.