It’s hard to imagine now, but there was a time when, if you didn’t know something and neither did your neighbours, you had to find a book and look it up. When I first worked in a library it was not unusual for people to phone us in search of answers to quiz questions, because unless you owned your own encyclopaedias, there was only one place to find help. So when I started to look at the story of one local library I was amazed at what a struggle its creation had been. Surely everyone would have thought a library was a Good Thing?

Evidently not.

| ||

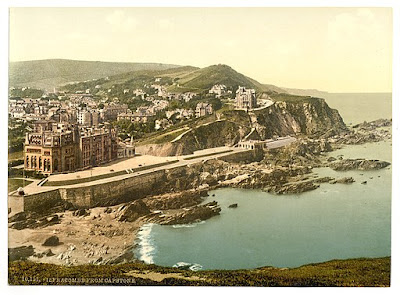

| Ilfracombe's seafront pavilion, c.1870 |

By the later years of Queen Victoria’s reign the small town of Ilfracombe, on the coast of North Devon, was a thriving holiday destination. In the first decade of the 20th century the reading tastes of locals and visitors alike were catered for by no less than five subscription libraries. Readers could thrill to stories by Conan Doyle, Rudyard Kipling and Louis de Rougemont, whose controversial adventures included “Round the World on Wheels”, “Twenty-eight Days Without Food” and the alarming “Shot Through the Head with a Ramrod.”

| |||

| Louis de Rougemont |

From about 1850 onwards local councils were empowered to set up free public libraries, but take-up was slow. There was a flurry of activity around Victoria’s Golden Jubilee in 1887 but Ilfracombe’s attempts to join in did not begin until early 1899. On 14 January The Ilfracombe Chronicle & North Devon News printed a letter of support from an anonymous ratepayer who hoped the proposed library would prove “a counteractive influence to the public house.”

The Chronicle’s local columnist, “Man about Town,” was also delighted with the idea, declaring in the same issue that “A library open to all classes, rich and poor, is a great boon to professional men and artizans [sic] alike”.

Unfortunately not all the town’s councillors agreed with him.

“The… speeches of the members,” declared the disgusted Man About Town in his column the following week, “proved… that many of them know nothing at all about the question.” This, he felt, was the only possible reason for the Council’s “utterly inexplicable” veto of the proposal despite widespread public support.

He dismissed the counter-suggestion of a “voluntary library” as “twaddle,” and saw no sense in the decision to consult the ratepayers. Indeed, 94 out of 99 letters sent to the Council chairman were in favour of the scheme.

“In the course of my professional duties,” declared one, “I am constantly brought in contact with students who are hampered in their studies for want of a good reference library.”

Another claimed, “The people of this town are endowed with great natural intelligence, but have been unfairly handicapped in the pursuit of knowledge by the absence of such an institution.”

On 28 January Man About Town returned to the subject for a third week, confident that despite this setback the ratepayers of Ilfracombe would see their own public library before long. Other local papers were not so sure. He quotes the North Devon Journal as being “astonished” at the decision, but the Exeter Gazette concluded that it was “a wise one” in view of other pressing needs for funds. Meanwhile the North Devon Herald pulled no punches. There was, it said, “no valid reason whatsoever why the ratepayers should be taxed… to furnish folks with a very limited selection of books, which they would only grumble and cavil over… the public will always clamour for anything they can see a chance of getting for nothing.”

|

| Andrew Carnegie |

Should the town accept? A Carnegie grant would come with strict conditions, and the recipients were expected to find the library’s running costs for themselves. The council voted to receive the money, but in January of 1905 the Chronicle reported “great differences of opinion” at a lively public meeting:

Mr W Pile said "they should put every opportunity of improvement in the way of the young men of the town. (CHEERS)

"…Mr Dadds went on to say that public libraries were a failure nearly everywhere. (HEAR HEAR) What did they read in these libraries? (RUBBISH) The town was expecting to get a Higher Grade School, and did not need the library."

The report offers a great deal more in this vein, suggesting everyone present was having a marvellous time – until the vote. The count was 85 for the library, 100 against.

Nevertheless, plans for a library were approved in 1912. There then follows a long silence, only partly explained by the interruption of the Great War.

On 23 May 1925 the Ilfracombe Chronicle Gazette and Observer ran the subtitle, “Carnegie Trustees want something definite”. This was not unreasonable, as “It is now more than 20 years since the promise was made by Mr Carnegie” and there was neither a library nor any obvious sign of one. The council, still mired in complications over the site, voted to adjourn.

It was not until 1934, 35 years after it was first proposed, that Ilfracombe’s Free Public Library finally opened in the rest room of the magnificent Ilfracombe Hotel - “lofty and airy, flooded with light from the glass dome roof.” (The hotel is the large building on the left in the picture.) There were 820 fiction, 300 juvenile fiction, and 440 non-fiction and reference books. It was created with help of the Devon County library service, which had received substantial help from the Carnegie fund and had set up 463 branches across Devon. The Ilfracombe Chronicle & North Devon News shared the good news on 14 December.

"…Mr Dadds went on to say that public libraries were a failure nearly everywhere. (HEAR HEAR) What did they read in these libraries? (RUBBISH) The town was expecting to get a Higher Grade School, and did not need the library."

The report offers a great deal more in this vein, suggesting everyone present was having a marvellous time – until the vote. The count was 85 for the library, 100 against.

Nevertheless, plans for a library were approved in 1912. There then follows a long silence, only partly explained by the interruption of the Great War.

On 23 May 1925 the Ilfracombe Chronicle Gazette and Observer ran the subtitle, “Carnegie Trustees want something definite”. This was not unreasonable, as “It is now more than 20 years since the promise was made by Mr Carnegie” and there was neither a library nor any obvious sign of one. The council, still mired in complications over the site, voted to adjourn.

It was not until 1934, 35 years after it was first proposed, that Ilfracombe’s Free Public Library finally opened in the rest room of the magnificent Ilfracombe Hotel - “lofty and airy, flooded with light from the glass dome roof.” (The hotel is the large building on the left in the picture.) There were 820 fiction, 300 juvenile fiction, and 440 non-fiction and reference books. It was created with help of the Devon County library service, which had received substantial help from the Carnegie fund and had set up 463 branches across Devon. The Ilfracombe Chronicle & North Devon News shared the good news on 14 December.

|

| Ilfracombe seafront |

“I feel convinced,” announced County Councillor Mr RM Rowe, “that the provision of a public library will not only add to the amenities of this township, but will also bring a large measure of joy, happiness, culture and refinement to the inhabitants.”

The Ilfracombe Hotel is long gone, but the public library which began life there is still bringing joy, happiness, culture and refinement to the town. Sadly I have searched the catalogue in vain for “Maid with the Goggles”.

*****

Thanks to Ilfracombe Library, who inspired the original research, and Ilfracombe Museum, who provided most of the material. All errors are of course my own.

For a brief summary of the rise of English public library (with occasional refs to NI, Scotland & Wales) visit the Historic England website.

For more on Andrew Carnegie, visit the website of the Carnegie Corporation.

*****

When she isn't hanging around museums, libraries and archaeological holes in the ground, Ruth Downie writes a series of murder mysteries. They're set mostly in Roman Britain and feature army medic Gaius Petrieus Ruso, and his British partner Tilla. To find out more, visit www.ruthdownie.com

*****

Pavilion - Francis Bedford, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Louis de Rougemont - George Newnes, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Andrew Carnegie -User Magnus Manske on en.wikipedia, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Ilfracombe sea front -Photochrom Print Collection, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Ilfracombe sea front -Photochrom Print Collection, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons