|

One day I wandered into a little temple called Kōtō-in. I sat on the veranda, gazed at the sand and rock garden and idly picked up the English-language leaflet. The temple, I read, had been founded in 1601 by Hosokawa Tadaoki, a samurai lord whose wife had been a Christian convert and who was a famous bowman. There in one of the paper shoji screens was the very hole through which he had shot three arrows - one after the other, with perfect precision.

|

| Map of Japan with picture of Will Adams meeting shogun, 1705, by Pieter van der Aa |

Reading it again more than forty years later, having spent much of that time absorbed in Japanese culture and history, I’m hugely impressed with how accurate it is, not just in the historical detail but in Clavell’s insight into how it feels to be Japanese.

James Clavell

Clavell led quite a life himself. Born in 1921 into a Royal Navy family, he was captured by the Japanese and interred in Changi prison throughout most of World War II. He went on to become a screenwriter and director in Hollywood. He wrote his first novel, King Rat, in 1960. Shōgun was published in 1975 and sold more than 15 million copies. Apparently it took him three years to research and write and he didn’t plan it out. Some of the plot twists, he said, were as much of a surprise to him as to the reader. He died in 1994.

|

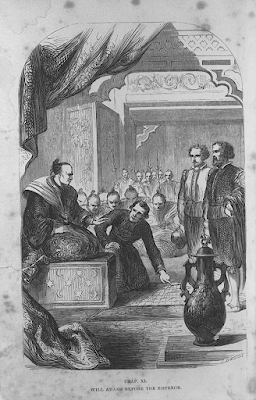

Closeup of Will Adams meeting the shogun, |

Literature or not, it is undoubtedly one of the most enjoyable books you will ever read and a brilliant source not just of Japanese history but of east west relations at the time, not to mention ships and nautical matters. Clavell’s skills as a screenwriter are readily apparent. Shōgun is dramatic, cinematic, a master class in historical fiction, immersing you in seventeenth century Japan and keeping you hooked from beginning to end.

William Adams the Pilot

|

| Will Adam's ship Liefde lands in Japan - monument in De Liefde arrival memorial park, Kurushima, Usuki City, by N. Tamada |

Clavell leaves the framework of history pretty much as it is. But he changes the names of the players which allows him to fictionalise freely, taking liberties with the details to make the story even more gripping and exciting. Readers are kept on their toes, anxious to find out how the characters will weather the next terrible ordeal that befalls them.

|

| Tokugawa Ieyasu by Kanō Tanyū (1602 - 1674) |

Only one man can control them - Blackthorne, tough, competent, fearless and, as we soon discover, the best pilot on the planet. We learn about their nightmarish two year voyage, in which all the other ships in the fleet were lost, and the rough Elizabethan world that he comes from. As a Navy man, Clavell lards his tale with colourful and authoritative detail about ships, seas and how ships work, the job of the pilot, who commands the ship, and the importance of rutters - the annals which pilots kept, laying down their routes and recording their daily activities.

After the horrors of the tempest comes a complete change of pace. Blackthorne wakes up in a small house in a fishing village in Izu. We see Japan through his eyes - the neatness, cleanliness and occasional nakedness, the Portuguese priest who declares him a pirate and demands he be killed, the samurai casually lopping off a man’s head. Clavell has a lot of fun with cultural differences such as the bath, a daily necessity to a Japanese but a death sentence to an Elizabethan Englishman. The bath becomes a marker of how Blackthorne is adjusting, as he starts to compare the sparkling clean Japanese houses and cities with the disease-ridden filth back home.

|

| Will Adams meets Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu - by William Dalton 1866 |

As the canvas broadens we meet an extraordinary range of people and start to see their world through their eyes as well as through Blackthorne’s. We also begin to discover how much goes on that Blackthorne knows nothing about.

We meet Mura the village headman, ‘small and lean with strong arms and calloused hands’ and a secret judo master; it’s many pages before we find out who he really is. Then there’s Omi, the handsome young samurai, who behaves with suitable disdain to Blackthorne and his crew and equally suitable deference to his uncle, Yabu, the daimyo of the region.

Yabu is a wonderful character, ‘short, squat and dominating,’ forever plotting who to betray in order to advance his own interests. He’s fearless and without scruples and finds death, his own and others’, both erotic and poetic. Early in the story he is trapped at the bottom of a cliff by the incoming tide. Having ascertained that there is no escape he sits down calmly to compose his death poem. Blackthorne meanwhile desperately seeks to rescue him even though Yabu has committed terrible deeds that make them deadly enemies. Yabu survives and continues to be a lethal yet strangely likeable and entirely untrustworthy presence throughout the book.

The women too are vividly portrayed. There’s Kiku the courtesan, exquisitely beautiful yet down to earth too. Her kimonos ‘sigh open’, ‘whisper apart’. Like a flower, her task is to rise above earthy reality, to laugh gaily and take men’s minds off whatever is going on around them, no matter how terrible. There’s also Gyoku-san, the Mama-san, who knows everyone’s darkest secrets, wielding them to advance her own position while appearing to be utterly humble, as a person such as she, on the bottom rung of society, has to be.

|

| Will Adams with daimyo and attendants by William Dalton 1866 |

Here he meets Toranaga, Clavell’s name for the great warlord Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543 - 1616) who was to become shōgun, taking over the whole of Japan and bringing about 250 years of peace. Toranaga is a consummate politician and statesman who controls and manipulates whatever happens and gives nothing away. He’s also likeable, warm and funny.

Blackthorne also meets Mariko, the Christian convert, modelled on Gracia, the wife of the warlord famous for his archery skills. Buntaro, Clavell’s fictionalised Hosokawa, is rather a tragic character. ‘A short, thickset, almost neckless man’, he is a brilliant warrior and a poet with the bow, utterly loyal to his lord. But he is also a man of terrifying rages, driven mad by his hopeless love for his wife.

Mariko is tiny, beautiful and fearless, a true samurai, prepared to die for her lord. She becomes Blackthorne’s interpreter, confidante and ultimately lover. She shows him how to flourish in this alien world by becoming more Japanese, finding inner peace.

|

| Tokugawa Ieyasu by Utagawa Yoshitora (1836 - 1880) |

At one point Mariko and Blackthorne are talking. ‘How childish’, she says to herself, ‘to speak aloud what you think.’ Like children, the westerners are what they appear to be. The Japanese conversely are eternally acting. Apart from Blackthorne, who is an outsider, they all know that this is how you play the game. Clavell gets a lot of fun out of the difference between what the Japanese say and what they’re thinking, let alone what they really intend to do. It’s a key distinction that Japanese recognise between one’s true feeling and the face that one chooses to present to the world.

As the story goes on the focus changes. Blackthorne slips into the background as we step more and more inside the fascinating and complex mind of Toranaga. Clavell spends a great deal of time unravelling the great daimyo’s innermost thoughts as he plays everyone like chess pieces in order to achieve his ultimate aim - to master and bring peace to Japan. Which is why the book is called quite accurately Shōgun.

There are occasional errors. Clavell confuses the shamisen (a lute) and the koto (a zither). He uses the wrong tea for the tea ceremony, and there are small mistakes with the Japanese language. Some of the names are a little odd. But none of this matters. The book is written with such verve that we are totally swept up in the excitement of the narrative and barely notice the occasional small hiccup.

To read Shōgun is to be picked up and thrown into Japan at one of the most exciting moments in its history. For Clavell totally gets Japan. He gets it right, it’s totally convincing, which makes it a great and very satisfying read even for a Japan hand after forty years of engaging with the country.

All pictures courtesy of wikimedia commons.

Lesley Downer is a lover of all things Asian and an inveterate traveller. She is the author of many books on Japan, including The Shogun’s Queen, an epic tale of love and death, out now in paperback. For more see www.lesleydowner.com.

|