|

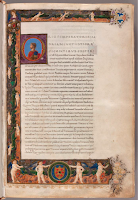

Boccaccio, De mulieribus claris (c. 1450-70, France) Phillipps MS 2862 |

Phillipps was a true bibliophile, writing in 1869 (presumably in jest):

''I am buying books because I wish to have one copy of every book in the world.''

But he was also stingy, a bully, a rabid anti-Catholic, a heavy-handed father, a ruthless hater and a maniacal collector who many timesalmost bankrupted his family in his quest to save manuscripts from destruction at the hands of those who saw no use for the old vellum.

But he was also stingy, a bully, a rabid anti-Catholic, a heavy-handed father, a ruthless hater and a maniacal collector who many timesalmost bankrupted his family in his quest to save manuscripts from destruction at the hands of those who saw no use for the old vellum.

Born the illegitimate son of a wealthy bachelor textile manufacturer and his housekeeper (or some say, a barmaid), the baby Thomas was formally adopted by his father, who had him educated at Rugby and University College, Oxford. Thomas's love for literature was obvious at a young age and was encouraged by his doting father.

When a very young child he began spending all his pocket money on buying books, which he kept, carefully arranged, in his bedroom. This predilection for buying old books and manuscripts increased when he was at Rugby and became somewhat of an obsession at Oxford.

Upon his father's death in 1819 he inherited a substantial estate and a country home, Middle Hill, in Worcestershire.

In 1819 he married Henrietta Elizabeth Molyneux, daughter of Major-General Thomas Molyneux, and they had three daughters. Phillipps's father had not wished him to marry Elizabeth, as she did not have a dowry, and there is some doubt that their marriage was a happy one. Phillipps memorabilia includes an imaginary map done in watercolour by Elizabeth demarcating ''The Shore of Courtship'' as a treacherous marsh.

But it was through his father-in-law's connections that Phillipps was created a baronet on 27 July 1821. His biographer, A.N.L. Munby, stated with regard to the baronetcy: ''Thereafter no holder of a centuries-old title could have been more insistent of the dignity of his rank.''

But it was through his father-in-law's connections that Phillipps was created a baronet on 27 July 1821. His biographer, A.N.L. Munby, stated with regard to the baronetcy: ''Thereafter no holder of a centuries-old title could have been more insistent of the dignity of his rank.''

In 1825 Phillipps was also appointed high sheriff for Worcestershire.

He spent almost his entire inheritance on manuscripts, books, antiquities and paintings, buying in a haphazard fashion.

|

| Scriptores Historiae Augustae (c. 1479, Florence) State Library of Victoria Phillipps MS 2163 |

My principal search has been for historical, and particularly unpublished, manuscripts, whether good or bad, and more particularly those on vellum. My chief desire for preserving vellum manuscripts arose from witnessing the unceasing destruction of them by goldbeaters; my search for charters or deeds by their destruction in the shops of glue-makers and tailors." (Phillipps, Preface to My Catalogue of Manuscripts (c. 1828))

On many occasions he seemed on the verge of ruin, but he never ceased collecting. When out of funds, he borrowed heavily to continue to buy.

"As I advanced, the ardour of the pursuit increased, until at last I became a perfect vello-maniac (if I may coin a word), and I gave any price that was asked. Nor do I regret it, for my object was not only to secure good manuscripts for myself, but also to raise the public estimation of them, so that their value might be more generally known, and, consequently, more manuscripts preserved. For nothing tends to the preservation of anything so much as making it bear a high price." (Phillipps, Preface to My Catalogue of Manuscripts (c. 1828)) Phillipps would go into book shops and purchase all the shop's stock, or he would buy every item listed in a dealer's catalogue. He had agents throughout Europe who would buy entire lots of books at auction, sometimes outbidding the British Museum.

His ability to collect in such numbers was assisted by the selling up of the contents of the monastic libraries after the French Revolution, and also by the relative cheapness of vellum material, such as English legal documents. Phillipps saw the value in old records thrown out by government departments and waste paper that otherwise would have been pulped.

Phillipps was ruthless with booksellers, arguing about their charges, refusing to pay their bills, refusing to return books. He sent several into bankruptcy.

At the age of thirty he fled abroad to avoid creditors, and found Europe in turmoil after the Napoleonic Wars. Manuscripts were freely available. Ignoring his debts he continued to increase his collection.

The Phillipps collection was truly eclectic, ranging from beautiful illuminated manuscripts which now enrich some of the world’s most exclusive collections to heaps of miscellaneous scraps of documents.

This is a re-creation of Phillipps’ shelves, now in the Grolier Club, New York

Phillipps pressed his wife, three daughters and their governess into the onerous task of listing his manuscripts and copying out those of particular interest to be published by him privately. They were forced to do do while living in a house that was almost uninhabitable due Phillipps's refusal to spend money on anything but his collection.

This is a re-creation of Phillipps’ shelves, now in the Grolier Club, New York

Phillipps pressed his wife, three daughters and their governess into the onerous task of listing his manuscripts and copying out those of particular interest to be published by him privately. They were forced to do do while living in a house that was almost uninhabitable due Phillipps's refusal to spend money on anything but his collection.

His long-suffering wife lived surrounded by boxes of manuscripts (the walls of her bedroom were so thickly lined with boxes that there was only a few feet of space for her dressing table); she became despondent, took to drugs and died at the age of 37.

Phillipps needed a rich second wife, and claimed that he was "for sale for £50,000", but he ended up with the amiable daughter of a clergyman who had a mere £3,000 per annum. It was a happy marriage nevertheless, until in his old age Phillipps became too eccentric even for her.

Phillipps needed a rich second wife, and claimed that he was "for sale for £50,000", but he ended up with the amiable daughter of a clergyman who had a mere £3,000 per annum. It was a happy marriage nevertheless, until in his old age Phillipps became too eccentric even for her.

Throughout his life Phillipps had a virulent hatred of Roman Catholicism and its practitioners. In 1826 he unsuccessfully contested the parliamentary representation of Grimsby on an anti-Catholic platform, and he was horrified by the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829, the culmination of the process of Catholic Emancipation throughout the UK.

What Phillipps feared was a Catholic coup in England. He was convinced that Jesuits were meddling with his mail:

"Your copy of the ‘Indication’...did not arrive this morning... Ought I not to have had it this morning? If I ought, then there has been foul play at the Jesuit Post Office here. Did you fasten it, so that it could not be taken out of the Envelope without violence? If you did not, it has probably taken a walk to the Jesuit Monastery here, for the edification of the FATHERS!!! You are not aware perhaps that this Post Office employs a Papist Boy to deliver Letters." (Letter Phillipps to Charles Bird of the Protestant Alliance 22 May 1863)

In furtherance of this hatred, Phillipps reported that he was “delighted to discover in his library and publish to the world evidence of unchaste practices in nunneries or the more curious details of Papal elections.”

Phillipps was able to publish such tracts by establishing in 1822 his own printing press, the Middle Hill Press. The press was housed in Broadway Tower, a folly built on Broadway Hill, Worcestershire, in 1798.

"Your copy of the ‘Indication’...did not arrive this morning... Ought I not to have had it this morning? If I ought, then there has been foul play at the Jesuit Post Office here. Did you fasten it, so that it could not be taken out of the Envelope without violence? If you did not, it has probably taken a walk to the Jesuit Monastery here, for the edification of the FATHERS!!! You are not aware perhaps that this Post Office employs a Papist Boy to deliver Letters." (Letter Phillipps to Charles Bird of the Protestant Alliance 22 May 1863)

In furtherance of this hatred, Phillipps reported that he was “delighted to discover in his library and publish to the world evidence of unchaste practices in nunneries or the more curious details of Papal elections.”

|

| Broadway Tower (author photo) |

Phillipps was able to publish such tracts by establishing in 1822 his own printing press, the Middle Hill Press. The press was housed in Broadway Tower, a folly built on Broadway Hill, Worcestershire, in 1798.

Middle Hill Press publications included books on local history and genealogy, rabidly anti-Catholic tracts, attacks on his son-in-law, but especially lists and catalogues of his own library and those of his book-collecting friends.

His temper and utter vindictiveness is evident in the story of how he treated his eldest daughter, Harriet, when she married James Orchard Halliwell against his wishes.

Halliwell had collaborated in research with Phillipps when still an undergraduate at Cambridge, and Phillipps invited him to Middle Hill for a visit in February 1842.

A romance developed between Harriet and the young man. Although Harriet had spent many hours of her life correcting proofs and copying letters for her father, her entreaties to be allowed to marry Halliwell were in vain. Phillipps refused to countenance the match.

The couple eloped, and Phillipps was enraged. He disowned Harriet and maintained a lifelong vendetta against her and her husband.

Phillipp's resentment at the elopement was exacerbated because an entail on the Middle Hill property secured it to Harriet after her father's death, so long as her husband took the name of Phillipps in addition to his own.

Phillipp's resentment at the elopement was exacerbated because an entail on the Middle Hill property secured it to Harriet after her father's death, so long as her husband took the name of Phillipps in addition to his own.

That meant his hated son-in-law would bear the name of Phillipps and live in Middle Hill! Phillipps found it insufferable. He tried to break the entail, but failed.

Halliwell was later to be a distinguished Shakespearean scholar, but there was some concern as to his integrity and Phillipps became convinced that Halliwell had stolen some valuable books from the library of Trinity College, Cambridge. Phillipps exploited this to the utmost, making accusation after accusation against his son-in-law, calling him a thief and liar who "persuaded his wife to play the whore and run away from her home."

Harriet attempted on many occasions to amend the breach between them, but Phillipps was obdurate. This is an example of a reply to Harriet from her father:

"It appears that you have no power now Harriet to effect a reconciliation between us. The consequence will be that you will fall under the Curse destined for all disobedient Children ‘unto the 2nd & 3rd generation’. I understand the Curse had already commenced by your eldest Daughter being half-witted, & your second is afflicted with a Spinal Complaint. Your husband seems determined that the third shall also incur some misfortune by refusing to make me the Compensation which I understand he once promised.

In such case neither you nor he can expect any blessing of

To keep his collection and printing press out of the hands of Harriet and her husband, Phillipps decided to move from Middle Hill. He bought Thirlestaine House in Cheltenham from the estate of Lord Northam, who had housed his extensive art collection there. (The building is now part of the exclusive private school, Cheltenham College, which bought it from Thomas's descendants in 1949.)

Halliwell was later to be a distinguished Shakespearean scholar, but there was some concern as to his integrity and Phillipps became convinced that Halliwell had stolen some valuable books from the library of Trinity College, Cambridge. Phillipps exploited this to the utmost, making accusation after accusation against his son-in-law, calling him a thief and liar who "persuaded his wife to play the whore and run away from her home."

Harriet attempted on many occasions to amend the breach between them, but Phillipps was obdurate. This is an example of a reply to Harriet from her father:

"It appears that you have no power now Harriet to effect a reconciliation between us. The consequence will be that you will fall under the Curse destined for all disobedient Children ‘unto the 2nd & 3rd generation’. I understand the Curse had already commenced by your eldest Daughter being half-witted, & your second is afflicted with a Spinal Complaint. Your husband seems determined that the third shall also incur some misfortune by refusing to make me the Compensation which I understand he once promised.

In such case neither you nor he can expect any blessing of

Thos Phillipps" [1867]

To keep his collection and printing press out of the hands of Harriet and her husband, Phillipps decided to move from Middle Hill. He bought Thirlestaine House in Cheltenham from the estate of Lord Northam, who had housed his extensive art collection there. (The building is now part of the exclusive private school, Cheltenham College, which bought it from Thomas's descendants in 1949.)

Phillipps well knew the importance of his collection. Between 1828 and 1861 he negotiated with Oxford University, offering it to the university on the basis that it be kept together, housed at the Ashmolean and that he be appointed the Bodleian Librarian. Not unsurprisingly, the negotiations failed.

He corresponded with the then Chancellor of the Exchequor, Benjamin Disraeli in 1862, hoping that it would be acquired for the British Museum. Frederick Madden, Keeper of Manuscripts at the British Museum wrote in his journal: “Whatever may become of his vast collection of MSS, I trust they will not in my time come to the Museum, - at all events, if Sir T.P. is alive, to interfere with the arrangement and cataloguing.”

Phillips died at Thirlestaine House on 6 Feb. 1872, and was buried at the old church, Broadway, Worcestershire.

Phillips died at Thirlestaine House on 6 Feb. 1872, and was buried at the old church, Broadway, Worcestershire.He left his collection to his youngest daughter, and in his will stipulated that his books should remain intact at Thirlestaine House, that no bookseller or stranger should rearrange them and that his son-in-law James Halliwell and no Roman Catholic would ever to be permitted to view them.

|

| Thomas Fenwick |

But the enormous collection was too difficult for his heirs to maintain. In 1885, the Court of Chancery broke the trust created by his will and the collection was sold by his grandson Thomas Fitzroy Fenwick (d.1938) over the next fifty years. Fenwick reorganised and renumbered the collection and his estimate was close to 60,000 manuscripts (volumes and individual documents), 50,000 books and as many prints, photographs, drawings and paintings. It was sold off in bits and pieces between 1886 and the 1940s, but the final dispersal took over 100 years.

Much of the European material was sold to national collections such as the Royal Library in Berlin, the Royal Library of Belgium and the Provincial Archives in Utrecht. Magnificent individual items ended up n the USA at the Morgan Library and Museum in New York and the Huntington Library in California. But Phillipps manuscripts have ended up all over the world.

Phillipps undoubtedly saved many manuscripts that otherwise would have been lost. The Spanish documents referred to in the letter transcribed below are probably Phillipps MS 25342, a collection of documents from the Medina Sidonia archives. One of them contains the signed orders of Philip II of Spain, sending the Armada against England. It is now in the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich, but without Phillipps it would have ended up wrapped around someone's groceries:

"More MSS. are destroyed by ignorant people, than by civil wars – I once found a bookseller at Madrid occupied in taking off the parchment covers from a large pile of old folios and throwing them inside into his cellar to sell by weight to the grocers: I opened one, and immediately bought the whole (120 volumes) at about 2s. per vol: you will hardly believe that among them was one of the most precious volumes in your collection; a volume of original documents relating to England in the time of Philip the second! – But it is not in Spain alone that these things occur, for I bought in London the original papers and correspondence of Govr Bernard, Govr of Massachusetts at the commencement of the American War; which had already been sold for waste paper: and partly used as such!"

Bookseller Obadiah Rich to Phillipps, 1843

How much did the collection cost?

Total cost

•£200,000 – £250,000 (Munby’s estimate)•Phillips's spent an average £4,000 – £5,000 a year for fifty years

•Phillipps’s annual income was about £6,000

•Most expensive single item: £590 in 1857

What are these figures worth today?

•£149,000,000 – £186,250,000•£2,980,000 – £3,725,000 p.a.

•£4,470,000 p.a.

•£375,000

Converted using “Average Earnings” method:

Lawrence H. Officer, "Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1830 to Present," MeasuringWorth, 2011 URL: www.measuringworth.com/ukcompare/

1 comment:

Sir Thomas Phillipps mother was Hannah Walton born circa 1770 in Sowerby Yorks, she was the daughter of one of Thomas Phillipps business associates and in his will, he left her an annuity of £50 a year for her sole use and not of her husbands, she had married Frederick Judd in 1812.

Sir Thomas Phillipps first wife Harriet Molyneux, was also illegitimate, as her parents were unable to get married till after their ninth child had been born, because her mother's first husband was still alive.

Post a Comment