|

| Castellani Medusa Cameo and Micromosaic Egyptian Necklace |

I’m not the only one who admires the exquisite jewellery of

the Etruscans (see my earlier post on Ancient

World Glitter and Glamour). In the mid-19th and early 20th centuries jewellers

and artisans were inspired by archaeological fashions. The most influential of

these was a Roman goldsmith, Fortunato Pio Castellani, and his sons, Alessandro

and Augusto, who rose to eminence through their introduction of the

neo-Classical revivalist styles. For three generations the Castellani family,

with the crossed ‘C’s as their hallmark, were at the centre of the

archaeological revival movement, which saw jewellery created in the styles of

the ancient Etruscans, Romans, Egyptians, Byzantine and Greeks of the 9th to

4th centuries BCE. Castellani based many of his designs directly on

archaeological evidence and often incorporated intaglios, cameos and

micromosaics into his jewellery.

|

| Castellani C19th/original C5th BCE millegrain pendants |

In 1860, Castellani was enlisted to be an advisor on the excavation of the Regolini-Galassi tomb at modern day Cerveteri. This site is renowned as one of the great treasure troves of Etruscan art. Castellani became fascinated by the brooches, earrings and necklaces found in the tomb which were studded with minuscule gold spheres, often smaller than a pin head. This ‘granulation’ technique was achieved without soldering and created an effect called ‘millegrain’ or ‘thousand grains.’ Knowledge of the craft of granulation was believed lost but Castellani discovered there were goldsmiths in the mountain villages near Rome who had preserved not only the secret of granulation but also another procedure called ‘fillegrain or ‘thread and grain/filigree’ where motifs were applied using thin gold wire.

|

| Castellani gold necklaces, amber & gold parure set, gold millegrain brooch |

The Castellanis owned a shop near the Trevi Fountain in Rome

where they assembled a magnificent collection of antiquities in their showroom.

Visitors could then buy replicas as a souvenir of their visit. Not so very

different from the ‘museum’ shops that await you when you try to exit from any

art gallery or museum exhibition today!

Emperor Napoleon III of France was a great lover of Etruscan artefacts, too. He bought the famous art collection of an Italian marquis, Giovanni Campana, which he exhibited in the Louvre. The Castallani family were commissioned to catalogue and restore the jewellery of the Campana Collection which enabled them to study ancient techniques and gain access to an enormous number of designs. By 1860 neo-Etruscan style pieces had become contemporary fashion accessories and remained in demand until the end of the century. At this point complete ‘parure’ sets of jewels appeared usually consisting of a brooch, necklace and matching earrings. In fact, a few years ago I attended a Titanic exhibition and was amazed to see neo-Etruscan jewellery on display which indicates the ‘fad’ was still in existence in the early C20th. Indeed, it was only when diamond jewellery became increasingly fashionable that the allure of the finely wrought gold pieces faded in contrast to the attraction of sparkling gemstones.

Wedgwood CeramicsEmperor Napoleon III of France was a great lover of Etruscan artefacts, too. He bought the famous art collection of an Italian marquis, Giovanni Campana, which he exhibited in the Louvre. The Castallani family were commissioned to catalogue and restore the jewellery of the Campana Collection which enabled them to study ancient techniques and gain access to an enormous number of designs. By 1860 neo-Etruscan style pieces had become contemporary fashion accessories and remained in demand until the end of the century. At this point complete ‘parure’ sets of jewels appeared usually consisting of a brooch, necklace and matching earrings. In fact, a few years ago I attended a Titanic exhibition and was amazed to see neo-Etruscan jewellery on display which indicates the ‘fad’ was still in existence in the early C20th. Indeed, it was only when diamond jewellery became increasingly fashionable that the allure of the finely wrought gold pieces faded in contrast to the attraction of sparkling gemstones.

Englishman Josiah Wedgwood was another artisan who was inspired by Classical artwork. His interest was sparked by discovering the various volumes in the Collection of Etruscan, Greek, and Roman antiquities from the cabinet of the Honble. Wm. Hamilton, His Britannick Maiesty's envoy extraordinary at the Court of Naples.

|

| Wedgwood black basalte urn/Etruscan bucchero jug |

Sir William Hamilton was the British Ambassador to the

Kingdom of Naples in 1764-1800 (His second wife was the notorious Emma

Hamilton, mistress of Admiral Horatio Nelson!) Hamilton’s collection of vases

and other antiquities were described as ‘Etruscan’ but in fact many of the

items described as such were actually Greek. However, this does not detract

from Josiah Wedgwood’s love affair with Etruscan ceramics. He established a

factory named ‘Etruria’ in 1769 in Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, which operated for

180 years.

The motto of the factory was ‘Artes Etruriae Renascuntur’ ie

‘The Arts of Etruria are reborn’. His most authentically Etruscan design was

his ‘black basaltes’ which were black, burnished and unglazed ceramics similar

to original Bucchero ware (see Black on Red, Red on Black: Figure it Out) Made

from reddish-brown clay which burned black in firing, black basalte owed its

richer colour to the addition of manganese.

Hamilton also inspired Wedgwood’s more famous ‘Jasperware’. When

the ambassador returned to England in 1783–84, he brought a Roman glass vase (known

as the Portland Vase as he sold it to the Duchess of Portland ) which was given to the British Museum. The relief decorations on the vase served as

inspiration for Wedgwood’s unglazed matte ‘biscuit’ Jasper stoneware produced

in a number of different hues such as green, yellow, lilac, and black. The best

known colour is the pale blue known as ‘Wedgwood Blue’. Decorations in

contrasting colours (typically in white) give a cameo effect to the ceramic. The cameos were initially in the Neo-Classical style but, over the centuries, were adapted to more modern subjects

including silhouette portraits of notable people.

|

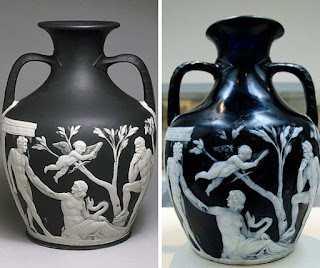

| Wedgwood copy/Roman Portland Vase |

Josiah Wedgwood’s copy of the Portland Vase proved to be

more valuable than its price. In 1845, a vandal called William Lloyd shattered

the original vase into 200 pieces. The British Museum’s restorer was able to

reassemble the classical vase by referring to Wedgwood’s own masterpiece.

Antique Wedgwood ceramics are sought after in auctions

houses around the world, but it is Castellani’s craftsmanship which provides

the best example of the value placed on neo-classical revivalism. A set of gold

tasselled earrings (depicting the god Apollo riding his horses upon a crescent

held aloft by two angels) was the subject of a bidding war in 2013. Estimated

at $6000, it eventually sold for $169,000! However, no matter whether it is an

original or replicated piece, I always wonder about the women who wore cherished

pieces of jewellery be they ancient Etruscan princesses laid to rest in tombs

or an ill-fated passenger who ended her life beneath icy waters.

|

| Castellani earrings/Wedgwood Blue Jasperware |

2 comments:

This was a fantastic reminder: if we want to write about a long-forgotten era, we can access it via writing about its beautiful objects. Thank you, Elisabeth.

Thanks for dropping by, Barbara! I know how much you value research.

Post a Comment