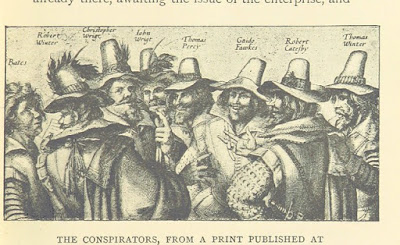

Mary Ward’s idea for a female religious order inspired by the Jesuits was not popular in Rome. It wasn’t popular in her native England either. The Gunpowder Plot was still within living memory, and two of Mary’s uncles had been amongst the plotters. They're shown in the engraving below: Christopher and John Wright, third and fourth from the left. Suspicion of Roman Catholics was rife. This was an age of secret Masses: of underground priests, of spies, tortures and executions.

Mary originally escaped the turmoil in England by joining a convent in St Omer, but found herself dissatisfied with the cloistered life that was demanded of women devoted to the church. She was convinced that God wanted her to do more.

“There is no such difference between men and women,” she wrote, “that women may not do great things.”

Returning to London, she established an undercover group of women who offered education, encouragement and practical support to persecuted Roman Catholics both in and out of prison. Confident that God wanted her to create an order of women who were free to travel and do his will wherever they went, she and a small group of sisters walked all the way to Rome to seek the Pope’s approval. Here’s a replica of the hat she wore for the journey:

Unfortunately Mary was not skilled in church politics, and the church was not skilled in communication. Not realising that the long silence from the Pope meant ‘no’, she went ahead, setting up groups of “Jesuitesses” who ran schools and communities in several European cities. Upon hearing rumours that the Church did not approve and that her groups were being disbanded, she wrote urging her colleagues in Trier, Cologne and Liege to ignore any orders of suppression. She was certain the Pope could not have authorised any such instruction.

Unfortunately Mary was not skilled in church politics, and the church was not skilled in communication. Not realising that the long silence from the Pope meant ‘no’, she went ahead, setting up groups of “Jesuitesses” who ran schools and communities in several European cities. Upon hearing rumours that the Church did not approve and that her groups were being disbanded, she wrote urging her colleagues in Trier, Cologne and Liege to ignore any orders of suppression. She was certain the Pope could not have authorised any such instruction. The letter was more naïve than heretical, but the damage was done. This was disobedience, and disobedience had to be dealt with. The Inquisition was called in, and Mary was imprisoned while the church decided what should be done with her.

Mary seems to have been remarkably longsuffering in her imprisonment. But while she co-operated with the authorities on the surface, she also kept up a secret correspondence with her friends on the outside. As every schoolchild knows, but apparently Mary’s guardians didn’t, lemon juice dries invisible but can be revealed by warming the paper.

In the end she was not convicted of heresy, but neither was she fully freed. Her groups of “Jesuitesses” were ordered to be broken up and banned forever. As Urban VIII put it in his Papal Bull of 1631, they had been guilty of wandering about at will, “and under the guise of promoting the salvation of souls, have been accustomed to attempt and to employ themselves at many other works which are most unsuited to their weaker sex and character, to female modesty and particularly to maidenly reserve.” Furthermore they persisted in such activities, and were “not ashamed”.

Mary died with her life’s work apparently in ruins. However - some of the communities she founded managed to hang on by the skin of their teeth, although they were not allowed to acknowledge her as their founder.

|

| The Bar Convent |

The Bar Convent is still there: just around the corner from York station and close to the city walls. The sisters who live there belong to an order now called the Congregation of Jesus. They and their predecessors ran the school for almost 300 years, surviving the suspicious searches of officials, a rampaging mob (St Michael was apparently instrumental in seeing them off) and the threat of prosecution for non-attendance at Holy Communion in the local Anglican church. (The case failed when it turned out that the vicar hadn’t bothered to hold a service on the day in question.)

The convent has given sanctuary to refugees fleeing the French Revolution, to Belgian children and convalescing soldiers in the First World War, and to Bosnian children during the Balkan conflict.

The convent has given sanctuary to refugees fleeing the French Revolution, to Belgian children and convalescing soldiers in the First World War, and to Bosnian children during the Balkan conflict. It has also provided a discreet place of worship for Roman Catholics unwilling to surrender to the Church of England. The chapel, built in the 1760’s, is invisible from the outside of the building. I can vouch for the fact that its eight exits (in case a quick escape was needed) are very confusing to outsiders. There's also a hiding-place for the celebrant - a “priest’s hole” - which I never found.

The convent has now survived the departure of the school, which moved elsewhere in the 1980’s. Seeking a new use for the building that would allow it to cover its costs, the Congregation of Jesus hit upon hospitality - and this is where people like me come in.

The Bar Convent now offers a Bed and Breakfast refuge for visitors to the beautiful but exhausting city of York. It’s a peaceful haven with enclosed gardens, a stunning glass-roofed Victorian courtyard, a guests’ kitchen, a teashop, and a museum that’s well worth a visit. I stayed there earlier this month for the York Roman Festival and have already booked again for next year.

|

| The Victorian glazed courtyard dining area |

Finally, Mary Ward’s time has come.

Sources -

Bar Convent Heritage Centre website

Bar Convent information leaflet

Mary Ward - Under the Shadow of the Inquisition, by M. Immolata Wetter

The History of the Bar Convent by Sister Gregory IBVM,

Mary Ward by Sr Gregory Kirkus CJ

Any and all errors are Ruth's own!

Ruth Downie writes murder mysteries set in Roman Britain - find out more at www.ruthdownie.com

Eboracum Roman Festival is a splendid weekend for anyone interested in anything remotely Roman. Ruth's account of it is here. The next one will be held in York on 29-31 May 2020. If you want to stay at the convent, book now!

2 comments:

Ruth, a very interesting story of which I have to admit I was totally ignorant. It was good to learn of this little bit of history. However, I think your reference to Elizabeth's reign in you first paragraph is a bit chronologically confused.

Whoops - yes it certainly was, Mike. Thanks for pointing it out!

Post a Comment