Before I began to write the third book in

my Oxford Medieval Mystery series, The

Huntsman’s Tale, there was one area of research demanding my attention –

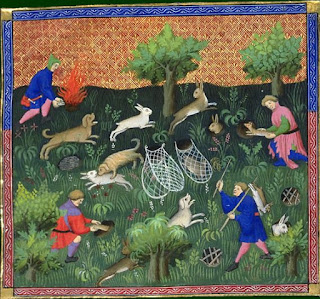

what exactly went on at a medieval hunt? Most of us are familiar with images of

medieval hunting, like the hawking scene from Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry:

And I suppose that we also know that the

origins of more recent forms of hunting, on horseback, with a pack of hounds,

must lie somewhere back in that remote past. Modern hunts have about them an

aura of wealth and privilege, and those medieval pictures show the nobility in

fine clothes, so it must always have been a pastime of the rich, mustn’t it?

Well, yes and no.

As I delved into the subject, I discovered

that everyone, from king down to villein, hunted as a regular part of life. At

any rate, every man, and quite a few

women. The nature of the hunt and the type of quarry varied, but everyone

hunted for food. Pursuing something as inedible as a fox would have seemed like

madness, unless it was to protect farm stock from a predator. Deer and boar

were the favourite quarries of the rich, but everyone hunted hares and rabbits

(usually called conies), either on horseback or on foot, and every type of

edible bird either with nets or birds of prey.

Two principal and invaluable contemporary

books on hunting survive from the Middle Ages. The Master of Game, by Edward, Duke of York, and Le Livre de Chasse, by Gaston Phébus,

Count of Foix.

Edward Plantagenet of Norwich

Edward Plantagenet had served as Master of

the Hart Hounds for his cousin, King Henry IV (amongst many other more obviously

distinguished posts) and wrote his book between 1406 and 1413, dedicating it to

the Prince of Wales, later Henry V. Gaston Phébus was obsessed lifelong with

hunting, and wrote his treatise in the 1380s. He died of a stroke at the age of

sixty, after an exhausting bear hunt. (All right, bears were a slightly more

exotic quarry in parts of Europe . Wolves were

also hunted as dangerous predators preying on farm stock, but by the late

medieval period had almost disappeared from Britain

The hunting of deer was the outdoor sport par excellence in England, and was

originally confined to royalty and nobility, hunting on horseback, with two

main types of dog – tracking dogs, often a breed called lymers (and also

precursors of the greyhound breed), and killing dogs, like the alaunt (a breed

now extinct, which seems to have resembled mastiffs, and could be dangerous

even to their own handlers).

Although a successful deer hunt would

provide food in the form of venison, participants also viewed it as both a

source of ‘delite’ and as a training for young men in many of the skills they

would need in mounted warfare. Deer were hunted in forests, chases, and parks.

A ‘forest’ was not a synonym for a ‘wood’,

it was an area usually belonging to the king which could include woodland,

heath, and even marsh. A forest was reserved for royal hunting, or for those to

whom the king gave a licence, and it was subject to strict forest laws. Those

who lived within the boundaries of a forest had certain rights (usufruct), but could also be severely

punished if they broke the forest laws. The term survives, for example, in the New Forest .

A ‘chase’ was a free liberty, and not

subject to forest laws. However, as time passed, the right to hunt in a chase

was granted more and more as a favour or reward to nobles, where the king then

enforced forest laws. The term survives in Cannock Chase.

A ‘park’ was an enclosed area in an estate

where a breeding herd of deer was kept for hunting, and belonged to the king, a

noble, or an ecclesiastical body. Those in holy orders were not above enjoying

the hunt, as Chaucer makes clear in The Canterbury

The kind of hunt which took place in a park

tended to be different from the day long pursuit of quarry on horseback over

often dangerous ground. The park was usually situated near a manor house or

hunting lodge, where spectators could view the hunt. Often the hunters would be

lined up – somewhat like the guns in a modern grouse shoot – and the deer would

be driven past them by the senior huntsman and his assistants. As the deer

passed, the hunters would aim their bows or crossbows and take down their

quarry at far less risk to themselves.

Although a few notable women took part in

the mounted hunt, it was more common for them to join one of these driven

hunts. Even well into old age, Queen Elizabeth I enjoyed this form of hunting

(as well as hawking).

Wild boar provided another noble quarry,

although by the late Middle Ages they were becoming rarer in English woodlands.

An adult male boar was a dangerous beast, which could kill a man, especially as

the final kill was often by a man on foot. A boar spear had a crosspiece on the

shaft, to halt the animal, for otherwise a boar was capable, even when speared,

of running up the spear as it plunged into him, and killing the hunter even as

it died.

These noble hunts were large affairs,

starting with an open-air meal, attending by ladies and other spectators as

well as the hunters. For preference this was served in a grassy clearing beside

a stream. The modern stirrup cup before a hunt is a vestigial survival of the

original hunt breakfast.

The hunt would be organised by the chief

huntsman, a man of considerable skill, whose salary might exceed that of

apparently much higher officials. Under him would be a large company of

assistants and dog handlers with their animals. The hunters carried horns,

which were used to sound various recognised signals (like a modern hunt). At

the kill, a most complex ritual was carried out, to butcher the animal, reward

the dogs, divide the venison according to established practices, and sometimes

even leave an offering in the wood.

Hares were also hunted. Although they did

not carry the cachet of the deer hunt, yet their speed, their cunning tactics,

and elusiveness meant that they provided an exciting ride for the hunters. Nets might also be used.

Men of a lower class than those nobles

granted the rights of the chase by the king did, nevertheless, sometimes manage

to poach deer, for those who were unsuccessful in concealing their crime have

left their names in the records of the courts. The names of those convicted

occasionally include women. Famously Shakespeare was alleged to have poached a

deer in the park belonging to Sir Thomas Lucy. There were also criminal gangs,

not unlike modern organised crime gangs, who poached on a massive scale.

Interestingly, they were often peopled by men of gentle birth, like the

notorious Coterel and Folville gangs in the earlier part of the fourteenth

century, and the gang led by Richard Stafford, known as ‘Frere Tuk’, a hundred

years later. These were not the stuff of romantic Robin Hood legends, but thugs

who terrorised whole communities.

Landowners frequently held ‘rights of

warren’, which meant they could build artificial warrens, in which rabbits were

bred for the hunt, although this was almost more like a form of farming, rather

than hunting. The conies brought in valuable income for their meat and

especially their fur. They were also frequently poached by commoners, who did

not need the elaborate equipment of the deer hunters. Some nets to cover the

escape holes, and an agile ferret or small terrier would serve. This was a form

of hunting – or poaching – often undertaken by women.

Commoners also used nets and traps to

capture other types of game, including wolves and foxes which preyed upon farm

animals, or when poaching deer.

Hawking was a sport for the rich. The birds

themselves were costly, usually imported. Several dealers in birds of prey are

to be found in the records, importing hawks of various types mostly from Arab

countries of the eastern Mediterranean . And

the expense did not stop there. Training a hawk to kill, but then return to the

hawker’s hand was a long and arduous process, demanding weeks or months of

constant attention and sleepless nights on the part of the falconer. The

falconers themselves were skilled and highly paid specialists, so only the wealthy

could afford trained birds.

There was also a very strict hierarchy as

to who might fly which type of bird of prey, from gyrfalcons (only for kings)

down to goshawks (for yeomen, if any could afford one). Ladies flew female

merlins. The Boke of St

Albans (1486) gives a comprehensive list, including some

unlikely hawkers, but then medieval people did so love lists!

- King: gyrfalcon (male or female)

- Prince: peregrine falcon

- Duke: rock falcon

- Earl: tiercel peregrine (male)

- Baron: bastarde hawk

- Knight: saker

- Squire: lanner

- Lady: merlin (female)

- Yeoman: goshawk or hobby

- Priest: sparrowhawk (female)

- Holy Water Clerk: sparrowhawk (male)

- Knave: kestrel

- Servant: kestrel

- Child: kestrel

I think some of these may be taken with a

pinch of salt. The last three probably refer to members of a noble hawking

party who were allowed to join in, but probably did not own the birds. On the

other hand, the clergy probably did.

Commoners also caught birds, especially

water fowl like ducks and geese, for eating, but used nets or sticky lime

spread on branches, which trapped the birds’ feet. They might also shoot birds

with bow or crossbow, using spaniels with their soft mouths to retrieve them,

again much like today.

Medieval hunting in all its variety is an

enormous subject, its rituals of the kill alone requiring much study for young

noblemen. It might seem a blood-thirsty business to the modern mind, but it was

not undertaken purely as an enjoyable pastime. Certainly those galloping

through a forest on a beautiful day and a lively horse would have enjoyed

themselves, but the primary purposes were to obtain food, to train young men in

skills for warfare, or to protect flocks and herds from predators – not

unworthy goals.

Ann Swinfen

http://www.annswinfen.com

http://www.annswinfen.com

5 comments:

Fascinating. Thank you.

Although the West Midlands is associated with industry and mean streets, there is an ancient hunting site stranded in Sutton Coldfield on the edge of Birmingham. It's called Sutton Park and you can find out more about it here:

Amazingly, it's never been cultivated although its archaeoogy goes back to the Stone Age.

I'll have a look, Susan. Cannock Chase is in the Midlands too, of course. It was also known as a refuge for outlaws! I wonder whether Sutton Park is protected by some ancient laws, as the New Forest is.

Great information, I remember the alaunts and lymers bought to life in your book. I are there any resources that give details of the species of hawk you mention as few names are recognisable now?

Maria - most of these hawks/falcons can be found in the RSPB book on UK birds of prey. The gyrfalcon, lanner and saker were imported from Europe (mostly eastern Europe). The bastarde hawk is probably a bustard. 'Tiercel' means one-third. Male hawks are normally one-third smaller than the females, so tiercel is usually equivalent to male. One theory is that rock falcon refers to the Scottish peregrine, i.e. coming from the mountainous regions and usually bigger and stronger than the English ones. I haven't gone into falconry in detail, as my hunters are pursuing deer!

Many thanks, I will look them up in said book, yes it was gyrfalcon, lanner and saker which were a mystery. I remember a' hobby' being mentioned somewhere in my readings. Interesting images you have posted

Post a Comment